- Kevin Goddard

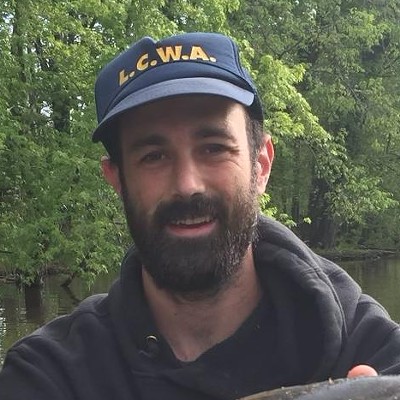

- William Siple and Sandy Harris riding Rural Community Transportation's "microtransit" bus

Burlington had never seemed so far away to Joel Rosinsky.

His heart was set on making it to the Flynn theater to attend a 50th-anniversary performance of Garrison Keillor's "A Prairie Home Companion" radio show, his favorite, on April 20. But Rosinsky, who no longer drives, faced a now-familiar conundrum: He had no way to get there from his home in Essex Junction, a mere 10 miles away.

Since Rosinsky gave up his driver's license three years ago because of eyesight loss to macular degeneration, his world has closed in on him. The nearest bus stop is a half-mile walk. The bus trip to Burlington can take 90 minutes, and service ends at 7:30 p.m., all but ruling out evening outings. A separate service for older Vermonters and people with disabilities, called the Special Services Transportation Agency, also quits at 7:30. When Rosinsky requested a ride from the agency a few weeks ago, it never showed up. Private rideshare services such as Uber are far too expensive for Rosinsky, who depends on Social Security.

Here he was again, trying to solve the puzzle of getting ... anywhere.

"Just having an evening where I can enjoy myself," Rosinsky said. "It's really complicated."

Before he lost the ability to drive, the retired social worker enjoyed meeting friends in Burlington for coffee. Rosinsky was "in the community," as he puts it, engaged in politics and eager to seize the day.

Now, he spends most of his time at home alone. A friend takes him grocery shopping once a week, but if he runs out of something, he has to wait. Rosinsky said he'd like to attend a support group for other legally blind Vermonters but has no way of getting to the meetings.

Having little to look forward to has thrown a pall over his daily life, making the mere act of taking care of himself a challenge.

Rosinsky's struggle is widely shared among older Vermonters who can no longer drive. Although the state's transportation agencies often shuttle seniors to doctor's appointments or the grocery store, the system falls short when it comes to just about anything else: seeing friends, entertainment, spending time in nature. Rosinsky lives in Chittenden County, the state's most populous county. Those who live in rural stretches have even fewer transportation options.

As Vermont's population ages, making it the third-oldest state, experts say the transportation gap makes isolation a growing problem. Loneliness is associated with higher risk for health problems such as heart disease, depression and cognitive decline among older adults, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It's associated with higher costs, too: an estimated $6.7 billion in additional federal Medicaid spending annually, according to AARP.

- Kevin Goddard

- Rural Community Transportation driver Caleb Grant

Driving is essential in Vermont, and deciding to give up the keys can be a wrenching choice for older people even as their skills, vision and reaction times decline. People over 65 have a higher likelihood of being injured or killed in a traffic crash, according to the state Agency of Transportation. Those odds increase with advancing age. Still, Vermont stands with Connecticut as the only two northeast states that don't require a vision test for older drivers renewing their licenses.

Erich Parent, an occupational therapist at Rutland Regional Medical Center who directs the hospital's driver rehab program, said the seniors he works with are often devastated when they learn it is no longer safe for them to drive. Parent helps older Vermonters sharpen their driving skills, prolonging the time they can spend on the road.

"Our clients — especially our rural clients — are put in this extremely difficult situation where they don't have the support necessary to exist in their home without driving," he said. "There's definitely not enough resources."

For older Vermonters stuck at home, life can become monotonous. Mary Cargill, 93, has lived for more than three decades in a home in rural Derby where she and her late husband raised six children. She doesn't want to move out but has had a hard time adjusting to life without a car.

"I hated giving up my independence," she said. "I have to wait until my kids are free to go anywhere. But I've always told them, 'I will not interfere with your lives.'"

Cargill spends most of her time puttering about her home. Meals on Wheels drops by twice a week. The volunteer driver, Brian Kuper, sometimes helps Cargill open the window or shovel her driveway.

Otherwise, Cargill waits for her son to take her to the grocery store or pharmacy after work. If he's pressed for time, he picks up what she needs on the way over. Cargill is grateful, but it means one less opportunity to be out in the world.

She at least has family nearby to help. Many seniors who live alone do not and depend on public transportation. The gaps in services exist even though Vermont stands out among the 10 most rural states by spending the most per resident on transportation. That money funds a network of regional transportation districts that provide bus rides, on-demand trips and other transportation services for residents across the state.

Vermont's Older Adults and Persons With Disabilities Transportation Program, or O&D service, funded largely through Medicaid, provides free medical trips for residents 60 and older and people with disabilities. In 2023, its drivers — some paid and some volunteer — made 112,000 total trips statewide. The program costs roughly $6.7 million a year, most of which comes from the federal government.

While such programs sometimes enable seniors to travel for nonurgent needs — such as buying groceries — more critical requests, such as doctor's appointments, usually take precedence.

"We can get you to the pharmacy or the grocery store or your doctor's appointment — that's one thing," said Ross MacDonald, public transit coordinator for the Agency of Transportation. "But we really don't cover many social trips." MacDonald said the agency has wanted to expand the scope of the O&D program, but budget cuts have gotten in the way.

Rideshares such as Uber are available in more populated parts of the state. But for older Vermonters living in rural Vermont — and anyone on a tight budget — the services are not a viable option.

Some regional transportation agencies are trying their own work-arounds. Rural Community Transportation, which serves the Northeast Kingdom and Lamoille County, is experimenting with a "microtransit" program in Morrisville to make rural transportation more flexible, particularly for elderly residents.

Since last year, the agency has provided a free, Uber-like service to Morrisville residents, who request a ride by using an app or calling the agency. Within hours, an electric van shows up at their door, including on evenings and Saturdays. AI software clusters trips to ensure that each rider reaches their destination by their requested time and also that the van is taking the shortest route.

The agency has provided more than 200 trips per week at just 60 percent of the cost of any of its other transportation programs. Residents have used the service to get to work, to court or just to enjoy a slice of pizza — all for free. Older residents make up a large portion of the riders. Many of them use it to get to day services for seniors.

- Kevin Goddard

- Chris Braithwaite

"It's been an unbelievable success, from all of my measurements," said Caleb Grant, executive director of Rural Community Transportation, which hopes to expand the program to Newport and Lyndonville next year.

On a recent weekday morning, the microtransit van picked up Sandy Harris, 78, and William Siple, 76, from a barbershop in downtown Morrisville. Both were heading back to their nearby senior housing complex. Siple had just given up his driver's license a few months earlier.

"I was nervous about what it might mean for my quality of life when I had to give up my license, but this has been great," Siple said of the service. "My life hasn't changed at all."

The Town of Essex offers something similar. Taxpayers fund a Senior Van, which allows older residents to get anywhere in town for free. The van has about 300 active riders, some of whom rely on it for their daily needs.

"Getting your hair done or getting your nails done is just as important for your mental health and your emotional health as it is for you to go to a doctor's appointment," said Nicole Mone-St. Marthe, the town's director of senior services.

Mone-St. Marthe has heard from other municipalities interested in replicating the program. "This should be looked at as an essential service," she said.

Although the transportation programs in Morrisville and Essex are promising, they serve a tiny portion of Vermonters. Rosinsky, for example, can't take advantage of the Senior Van because he lives in Essex Junction, which left Essex to become an independent city in 2022.

It's also often cheaper for transportation services when riders live downtown. MacDonald, of the Agency of Transportation, explained: "To serve 8,000 people in a seven-square-mile area, versus 8,000 people in a 200-square-mile area, is quite different from a cost perspective."

- Daria Bishop

- Joel Rosinsky

For Rosinsky, who grew up riding the bus and subway in New York City, that point is painfully clear.

"In some ways, it's easier to age in New York," he said. "Getting old in Vermont is complicated."

Rosinsky eventually solved his quandary over how to get to the Garrison Keillor show: The Special Services Transportation Agency took him to Burlington and a neighbor drove him home. Even after spending the following week cooped up and mostly alone, he sounded buoyed by his evening out.

"It's not necessarily about having a destination," Rosinsky said. "It's just about being out in the world."

Rosinsky envisions a life with reliable transportation. He'd go to more shows at the Flynn, grab a coffee with his friend or maybe stroll along Church Street. It would be enough, he mused, to buy a creemee and sit outside, enjoying the warming weather.

Correction, May 9, 2024: This story has been updated to reflect that Dana Rowangould said that providing downtown housing for seniors could be an additional way to address the transportation problem — not an alternative way.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.