- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

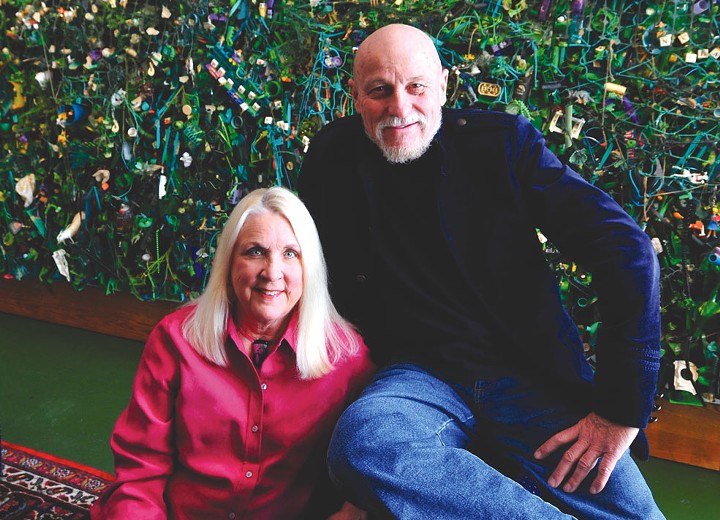

- Bobby and Billi Gosh

Bobby and Billi Gosh have spent their lives on the edge of the spotlight. When Frank Sinatra first listened to the demo of “My Way,” it was Bobby’s voice he heard singing it. The song that blasts out of that animated clock at FAO Schwarz in Manhattan was written by Bobby Gosh. Björk’s music-box tracks on her 2001 album Vespertine? She recorded them in the basement studio of the Goshes’ central Vermont home.

And then there’s Billi, a political dynamo in the Vermont Democratic Party. She was a “superdelegate” to the 2008 Democratic National Convention, led the Vermont Women’s Caucus, spearheaded the Vermont Women’s Fund, and helped women candidates get elected in Vermont and beyond. But she has never run for office herself.

You wouldn’t expect to find a couple so connected living at the end of an unpaved road, but the Goshes have resided in Brookfield among an ever-expanding art collection for the past 36 years. The place is so tricky to find, the two have become experts at giving directions. It’s well worth the trek.

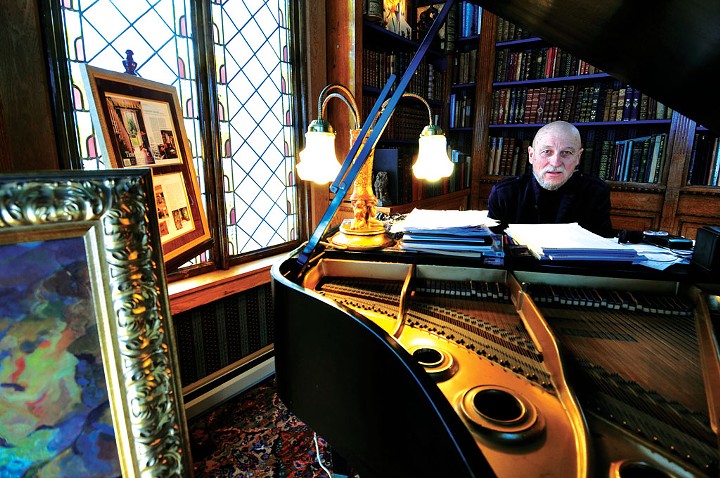

If they’re weary of conducting the room-by-room tour — which they’ve led countless times — it doesn’t show on a recent visit. Billi’s wearing kitten heels, black slacks and a pink button-down shirt. Gold dangly earrings brush against her long, platinum blond hair. She’s 74, but no one would suspect it.

Bobby, 75, is wearing a dark blue turtleneck and jeans. He’s got a white goatee but is completely bald and has been that way since his early twenties: When his hairline began receding, he shaved his head. “There goes Mr. Clean,” he remembers people calling out after him.

The unabridged tour takes most of a day, but the Goshes break it up with a long lunch. They’re practiced entertainers. For about a decade, until 1987, the couple owned a restaurant in downtown Randolph called Victoria’s. New Yorker cartoonist and fellow Brookfielder Ed Koren remembers the place well. “It was kind of Bobby and Billi incarnate in a restaurant: very funky, larger than life,” he says. “Not many people are that much larger than life — in a good way. Their munificence is large. Their hospitality is large.”

When they bought the house in 1971, Bobby was doing commercials in New York City, their son, Erik, was 3, and Billi was pregnant with their daughter, Kristina. It served as a ski house for the first four years they owned it, a simple ranch with gray linoleum floors. When she saw the place, Billi recalls thinking, “We’ve made a huge mistake.” It may not have been perfect, but it had what they were after: a view. The windows look out on uninterrupted fields and mountains in nearly every direction.

The Goshes moved to Vermont for good in 1975 and since then have transformed the place into a sprawling wonderland of edgy artworks and repurposed architectural details. The formal living room — where their friend Carol Hall performed the songs she wrote for Best Little Whorehouse in Texas before the musical debuted on Broadway — consists of antique shelving from a pharmacy and doors from the old mansion of Col. Robert Kimball, the Randolph financier who donated that town’s library. Walk into the bathroom off the Goshes’ bedroom and you’re transported to a Randolph barbershop circa 1919, with all the sinks, cabinets and mirrors just as they appear in the local newspaper clipping of the shop that hangs framed on the bathroom wall.

Bobby and Billi seem to share everything, from their enthusiasm for art and salvaged home décor to the pride they take in their individual accomplishments. Over lunch, when Bobby starts singing the jingle he wrote for Post Honeycomb cereal, Billi chimes in with all the words: “Come to the Honeycomb Hideout!” Other television jingles at the time had sweet-sounding vocals. “I was the first guy to sing like Joe Cocker [in an ad],” Bobby says. The residuals rolled in from that Honeycomb hook for about a decade.

In the ’70s, Bobby swore he’d never spend more than five days at a stretch away from Billi. Remarkably, more than 50 years into their marriage, they’ve made good on that promise. “We support each other,” Bobby says. “If she’s doing politics, I’m out there with her. If I’m doing music, she’s with me.”

It’s clear they’re devoted. Vermont Sen. Dick McCormack (D-Windsor), who has performed in several of Bobby’s jingles — once as a singing head of broccoli — remembers the day years ago when he noticed just how in love his friends were. They were all drinking wine and eating shrimp cocktail at a horse event in Quechee. “I look over at Billi, and rarely have I seen someone so visibly pleased,” says McCormack. “[She has] this look of almost amazement, like, How did my life turn out like this?”

She turned to her husband, who had his feet propped up on the chair in front of him, and said,“‘Bobby, isn’t this lovely?’ And he responded, ‘It’s so fucking lovely, I could shit,’” McCormack recalls, laughing. “I had this flash of anger at him … How could you rain on her parade like that?” But when McCormack looked over at Billi, he saw she was gazing at Bobby “with such delight, like she’s thinking, What a funny guy!”

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Bobby Gosh

Bobby grew up in Reading, Pa. His German father had immigrated there in the 1930s, just as Hitler was gaining momentum. The senior Gosh landed a job repairing the knitting machines at a nylon-stocking factory in Reading — “He could repair anything,” Bobby recalls — and married a Pennsylvania Dutch woman. They had Bobby in 1936 and his brother five years later.

Meanwhile, Billi, born Betty Ann Williams, grew up in the commuter town of Upper Montclair, N.J. Her dad worked in public relations for the Society of the Plastics Industry in New York City. Her mother, who trained in Vienna as an opera singer, also worked in the city, as a file clerk, and moonlighted as a singer. They divorced when Billi was 5.

Billi took on her new name — the kids at camp used to call her Billi, for her maiden name — when she started at Albright College in Reading. That’s where she met her future husband. She and Bobby were in the same class but moved in different circles. He was a day student; she lived in a dorm. He majored in business administration; she in French and English. Billi was “pinned” to an older guy who had left for medical school; Bobby, who wore a ring on his finger, was engaged to a girl from town.

“I thought he was married,” says Billi. She also thought he was “sort of a geek.” He carried a briefcase around campus and avoided the college scene, focusing instead on his music. Billi, Bobby recalls, was “a pretty big deal on campus.”

The two met one night in 1957. Billi’s girlfriend had convinced her to go to a Reading bar to see an act called the Sangfroid Trio. Her friend had a thing for the saxophone player, and soon Billi found herself smitten, too — with the pianist, Bobby Gosh. “He was a great musician, playing all these romantic songs,” she says. They talked and flirted after his set until curfew rolled around. “In those days, you had to be back to the dorms by 11,” Billi recalls.

Bobby wasn’t going to let this girl just slip away. He laid it on thick: Had she ever snuck out of the dorm? Would she like to accompany him to the after-party with all the other musicians? There’d be more music, and great food, he assured her. How could she say no?

She couldn’t. Billi left with her girlfriend, but not before arranging a secret signal system with Bobby. He should come to the dorm on his own and wait outside. If the Venetian blinds were closed, it meant she’d failed to get out and he’d have to leave. If they were open, she’d successfully escaped out the window and was hiding in the bushes below.

Sure enough, Bobby found the blinds open and Billi in the bushes. She’d stuffed her uniform for the next day’s work shift into her pocketbook. “We stayed up all night,” Billi recalls.

That week, Bobby broke up with his fiancée. The next, he introduced Billi to his parents. By 1959, they were married — and inseparable. After a couple years in Pennsylvania, where Billi taught elementary school, they moved to New York City so Bobby could immerse himself in the Big Apple music scene.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Bobby Gosh

By the time Bobby was 16, he was already orbiting musical stars, spending his free time watching jazz greats perform at Birdland and playing the piano for popular singer Kitty Kallen. He only went to college, he says, because he had a scholarship. It was his backup, in case he couldn’t cut it in the music business.

Right after graduation, he interviewed for a job with IBM. “You had to have a suit and a tie,” he says with disdain. “You had to have a white shirt; you couldn’t even have a blue shirt.” The first question out of the interviewer’s mouth, Bobby recalls, was, “Why do you want to work at IBM?” Bobby stared at him blankly.

“I went to Julliard to study orchestration instead,” he says. “Never looked back.”

On their first night in New York City, in 1962, the Goshes were unloading a moving van. Someone walked by, saw the musical equipment and offered Bobby a gig at a club that night. “It was like a Woody Allen movie,” Bobby says.

Before long he was writing songs with Sammy Cahn, the lyricist who wrote “Let It Snow,” “Time After Time” and “Second Time Around.” When they wrote “The Need of You” together, Bobby says, it was the first time he felt like a real songwriter.

It was through Cahn that Bobby met Paul Anka, who was looking for a piano player, in the late ’60s. Ultimately, the songwriter hired Bobby as the conductor of his 32-piece orchestra, but when they weren’t out on the road performing, they’d write songs together, too. Their relationship began to deteriorate, however, after a few songs Bobby says he and Anka wrote together made it to the charts without proper credit for Bobby.

Still, he was with Anka in Las Vegas when the singer wrote his biggest hit, the adaptation of a French song called “Comme d’habitude.” Gosh didn’t write any part of Anka’s “My Way,” but he was the first to sing and record the lyric.

Sinatra frequented Jimmy Weston’s supper club in New York, where Bobby played with a trio. One night in 1971, Sinatra came in with a huge party, including Tony Bennett, to hear Bobby play. He remembers Sinatra hushing everybody at the start of Bobby’s set so they’d give their complete attention to the music.

“It was very heady and flattering to have Sinatra care about listening to me perform, and I took it as some sort of stamp of approval of my talent,” says Bobby. “I’ll never forget it.”

It was also in Jimmy Weston’s where he got his start doing jingles. A guy came up to him one night and said, “Can you do commercials?” Bobby recalls.

Bobby agreed to try his hand at a tire ad. He never discussed money with the guy, but figured he could make a few hundred bucks. He had about 24 hours to come up with something, so he worked all night on a track with four rock guitars and some gruff vocals. The jingle house liked it and paid him a hefty sum — about $8000 for 24 hours of work.

“I came home and said, ‘I’m never doing nightclubs again,’” Bobby says. And he never did. Asked if he missed performing, he shakes his head and laughs. “If you ever want to know what it’s like, listen to ‘Piano Man.’” The microphone really does smell like a beer, he says. Billi agrees, scrunching up her nose.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Billi Gosh

Billi wasn’t always into politics, and she wasn’t always a hard-core Democrat. In Pennsylvania, she considered herself a Republican; after a few years in New York City, an Independent. While living in Manhattan, she kept her distance from politics. “I had a friend down the hall who was really interested in campaigns, and I couldn’t understand why she did it,” Billi says.

By the time she and Bobby moved to Vermont, she was starting to identify as a Democrat. But it wasn’t until 1979 that she became active in politics — because Planned Parenthood’s funding was being threatened. “To this day, it’s the superior provider of health care to all women,” says Billi of the organization. “For that to be threatened … I had to do something about that.”

So, that year, she learned how to lobby and take action at a daylong conference at Vermont Technical College. “I learned that, in Vermont, a couple of phone calls makes a difference,” she says. “Within a year, I was going strong,” pursuing issues such as domestic violence, workplace inequality and poverty.

In 1982, Billi worked to get Madeleine Kunin elected as Vermont’s first female governor — and she had Bobby’s help. He organized an unlikely campaign fundraiser: a musical tour, including performances by a variety of local acts, including Seven Days editor Pamela Polston’s new-wave band the Decentz and McCormack’s early rock-and-roll group Sal Paradise Junior.

“I addressed Madeleine Kunin as ‘Dollface’ in the voice of a rock-and-roll lout,” admits McCormack, who was not yet a legislator. If the governor-to-be was offended, she didn’t let on, he says.

“It turned out to be a lot of fun,” recalls Kunin. “The music was great, the posters were great, but the returns were not. I remember going and walking into this nearly empty hall.”

She lost that year — to incumbent Richard Snelling — but won the next election and appointed Billi to chair the Vermont Commission on Women. “She’s got a lot of energy,” says Kunin, who considers the Goshes friends. “She cares passionately about the issues. She seemed a natural choice.”

It was around that time Billi began itching to run for office herself. Not surprisingly, many people around her also started nudging her in that direction. But when Gov. Kunin called and asked her to run for the state legislature, Billi declined. She knew Bobby didn’t want her to. “I’ve seen it ruin some marriages,” he says.

“It was disappointing,” says Billi. “But his point was well taken. It’s hard enough running for office. If you don’t have your family backing you, it makes it that much harder.”

Instead, she commited herself to getting other women elected. Turns out, it suited her. When Deb Markowitz first ran for secretary of state 13 years ago, she came to visit Billi to talk about her chances.

“I like being behind the scenes,” says Billi, who fundraises and networks for candidates.

More recently, she was helpful in the 2008 Democratic primary, as a passionate supporter of Hillary Clinton. “I stuck with her to the end, as I told her I would,” Billi recalls. Clinton is well suited to her current role as secretary of state, Billi says, but she still feels Clinton could have brought something invaluable to the presidency. “Obama has great generosity of spirit, there’s no doubt about that,” she says. “But I think she would play hardball, which he hasn’t.”

Amid all this, Billi raised two children and worked for 16 years as director of development for the Vermont Institute of Natural Science in Quechee. She led the Vermont Women’s Fund, which raised about $2 million in its first three years for programs that help women and girls. And then Billi turned to the arts, starting the Vermont Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

“She turns down an incredible amount of boards,” Bobby says. “And she cooks dinner and I do the dishes.”

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Billi and Bobby Gosh

Does a power couple like this ever “retire”? In many ways, Bobby says, he feels his career is behind him. After he left Paul Anka, he released three albums of his own, and his song “A Little Bit More,” recorded by the band Dr. Hook in 1976, made no. 11 on the U.S. and no. 2 on the UK charts.

“Let’s face it, there’s not a big market for 75-year-old singers,” he says. “But I have a lifetime of experience, and I know I’m a songwriter because I’ve proved it.”

Still, he wants to stay in the game. At the moment, that means writing timely singles, such as his latest, “Nice to Be Johnny Depp,” which he’s hoping will make it big on YouTube. He has a lot of fun with it, and “it’s a way of keeping alive in the business,” he says.

As for Billi, she’s facing some of the same battles she thought she’d won years ago, including the threat to Planned Parenthood’s funding. “I think it’s a war on women,” she says. But she hasn’t lost hope. “It would be nice if we could concentrate on other issues, like domestic violence or pay equality, but we keep getting diverted,” she says. “We keep fighting the same battle over and over again. I’m in it for the long haul.”

Her most recent political win, though, was a strictly local project: at town meeting, Brookfield residents voted to appropriate $20,000 to outfit the town hall with composting toilets, so the place can be used for community events and concerts. “It was such a thrill!” Billi says, her face aglow. Standing by her side, Bobby glows right along with her.

— M.J.

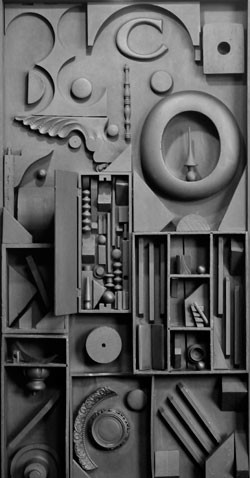

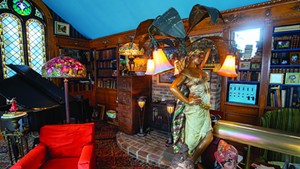

Cool and Collected

The Gosh Gallery Is a Tour de Force

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- "Stroking Monet" by Tom Deininger

It must be nice to live in a museum. That thought occurs to a visitor during a stroll through Bobby and Billi Gosh’s art-filled home — Bobby doing most of the talking, Billi filling in this or that detail while attending to emptied glasses of wine. Both are gracious hosts who seem to delight in talking about the paintings, sculptures, antique oddities, rare books and other items they’ve amassed, and the artists who created them. Bobby particularly relishes the unexpected discovery, such as finding three rather good paintings for a dollar at a secondhand shop, or coming across an unknown or underappreciated artist whose works have subsequently escalated in value. If serendipity and getting a good deal are part of the fun of collecting, having a colorful story to tell later seems to be part of the payoff.

Bobby had occasion to tell those stories to collectors affiliated with the Smithsonian American Art Museum last fall, when 25 members of its exclusive American Art Forum came for the tour. The Goshes’ house was one of just three venues the group visited in Vermont; another was the Shelburne Museum. It was a validation to the Goshes that their art instincts hold up to a discriminating audience.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Bobby and Bill Gosh's home

One thing Bobby makes perfectly clear when he talks about art, though, is that he doesn’t buy it for the investment. The impulse to bring it home is more visceral than that: “If I see a work of art and it really moves me, if I can afford it, I’m the kind of guy who wants to own it,” he says.

This passion has driven Bobby to acquire 1300-plus items over the past 40 years — with his wife’s approval. “We have compatible tastes,” he says.

“We temper each other,” Billi adds. And though she acknowledges her husband is the “major collector,” she agrees with the motivation: “I love art and cannot imagine life without it.”

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Bobby and Bill Gosh's home

To Bobby, the best way to support artists is to buy their work and promote them. Billi’s advocacy has another outlet: In 2001, she founded the Vermont Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, a group that juries Vermont artists for a biennial exhibit at that Washington, D.C., institution. For both Goshes, art is a necessity. As Bobby puts it, “I wake up in the morning and feel good to just look at it … Art is the soul of our house. If you took the art away, I’d feel like I was living in a cave.”

The Goshes’ exhibition actually begins outdoors, with the large-scale, steel-and-stone sculptures by Vermont artist John Matusz sited around their yard and along the drive. But in the winter, the tour commences as soon as one of the Goshes opens the door; even the mudroom is lined with art. Just a few steps away hangs what Bobby calls “probably the most valuable piece in the house”: a 1951 signed and numbered M.C. Escher lithograph, titled “The House of Stairs.” He bought it, he says, after the couple sold their Randolph restaurant, Victoria’s, in 1987.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Bobby and Bill Gosh's home

There’s not a lot of wall space left uncovered in this 20-room home, which began as a modest late-’60s ranch house with a spectacular view of Killington. The landscape, of course, is still there, and development free, but the living quarters have expanded substantially over the years, one addition at a time. The warren of rooms is rather like an unfolding treasure chest: Each divulges more art — a leather mural depicting Queen Victoria; wood assemblages by the late Vermont artist Jane Farrell; early, funky furniture by Stephen Huneck; apocalyptic paintings by Philip Hagopian; staid portraits in “the 1860 room” — and evokes corresponding commentary from Bobby. A small study is primarily devoted to one of the couple’s most important collections: oils and watercolors by the late Vermont painter Ronald Slayton (1910-92). In fact, only a fraction of their more than 200 pieces by Slayton are on view; many remain unframed and in storage.

Some of these paintings were loaned to the Fleming Museum of Art last summer for an exhibit that Bobby helped initiate. “A Centennial Celebration: The Art of Francis Colburn and Ronald Slayton” presented the two Vermonters — born just a year apart and lifelong friends — whose artistic styles overlapped in the late ’30s and early ’40s with their social-realist paintings created for the Works Progress Administration. Colburn, founder of the University of Vermont’s art department and the namesake of its gallery, gained greater recognition over the course of his career, and his style continued to evolve, says Fleming curator Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. Slayton, on the other hand, might have been relegated to Depression-era art history if not for Bobby Gosh.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

Slayton was restoring a painting while manning his junk-filled sale barn in the early 1980s when Bobby happened by. It was art-love at first sight. The painting belonged to the T.W. Wood Gallery, as Slayton’s son Tom tells it now, and was not for sale. So Bobby bought some other pieces instead. And kept buying them. “Ron was so disillusioned when I met him, he basically wasn’t painting anymore,” says Bobby. “I got him some work, and it spurred him to paint again.” That work included a show at the Wood, where, ironically, Slayton had been a curator for 18 years.

Tom Slayton, a writer and former editor of Vermont Life, verifies that story. “Bobby basically restored him to fame,” he says. “In my opinion, he put Dad back on the map, and gave him some of the recognition he deserved.”

Even after Ronald Slayton’s death, Bobby continued to champion the painter, efforts that ultimately resulted in the Fleming’s Slayton-Colburn exhibit. “When Bobby goes for an artist, he’s really all in,” notes DeGalan, adding that the show resulted in a “rediscovery” of Slayton. “He was sort of the underdog in that exhibit, but he came through really strongly,” she says. “People have been asking about some of his works.”

Now, Bobby Gosh’s promotional energies are focused on the Rhode Island-based installation artist Tom Deininger. In fact, the Goshes added a room to their house solely to accommodate half a dozen large-scale Deininger works — “Plastic Paradise” is 20 feet wide by 12 feet high and had to be installed in eight sections.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

Bobby likes to tell how he discovered the artist, now 41, at a juried exhibit in a church in Newport, R.I., 11 years ago. While Deininger is not the first artist to put together three-dimensional assemblages of junk, he is one of very few who can make them look — from a distance — like paintings. In fact, the artist’s medium is “all the crap we buy and then throw away,” as Bobby puts it. Squint your eyes, or just stand 10 or 12 feet back, and you can see the exacting portraits, landscapes and other images; yet close up all you see is the painted detritus — including children’s toys, pharmaceutical vials and used syringes. A Deininger piece in an exhibit at Stowe’s Helen Day Art Center a couple of years ago looked like an autumn day in the woods, blazing orange and red. “Tom can do this because he’s an incredible painter,” Bobby says. “He has a piece that looks like a Caravaggio!”

Bobby reveals that the Smithsonian American Art Museum expressed interest in Deininger, and he wasn’t surprised. “I think Tom is going to be in major museums all over,” he predicts. “One of the Smithsonian people called him the [Albert] Bierstadt of the 21st century.

“In some ways Tom has replaced Ron Slayton for me,” Bobby continues. “They’re both social realists in their own way. Tom is taking stuff that would go in a dump and making art.”

Another thing these two — and, for that matter, all the other artists in the Gosh collection — have in common: “It’s not safe art,” says Bobby. “No, we don’t have much of that.”

— P.P.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.