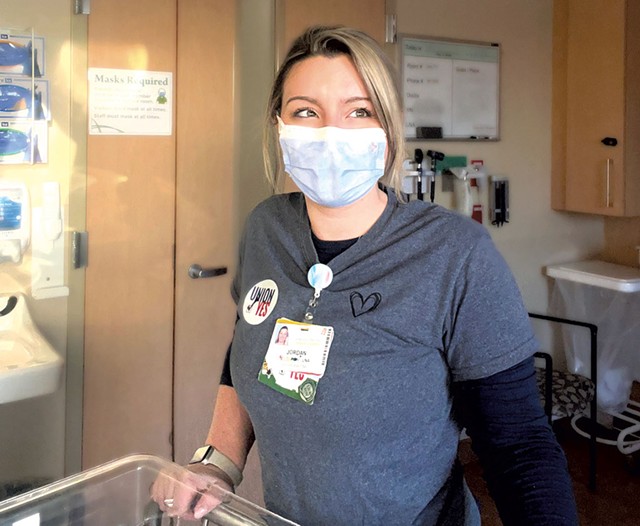

- Courtesy Of Jordan Bushway

- Jordan Bushway

University of Vermont Medical Center support staffers' vote to unionize last month was one of the largest labor elections in state history. Yet the landmark organizing drive, waged by the 2,200 lowest-paid workers at the state's health care behemoth, was easy to miss.

The technical professionals, nursing assistants and service workers, who together voted 1,120-181 to join AFT Vermont on January 27, didn't publicly campaign ahead of the election. The magnitude of their win was lost in the news cycle; members of the state's congressional delegation, who often leap over one another to signal their pro-union sympathies, did little to herald the organizing victory, though union sources told Seven Days that U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) met privately with workers in December.

The under-the-radar campaign among hospital employees who had tried and failed to organize many times before reflects a new labor climate. Pandemic-weary workers, toiling in understaffed workplaces only to see rising housing prices and inflation gobble up their earnings, want more.

Newly unionized workers are demanding $20 an hour, to be precise. Hospital support staff are the latest group to organize through AFT Vermont, which has doubled in size over the past five years and now represents roughly 8,700 workers. Many of these newly represented workers have been quietly securing pay floors of $20 an hour. But the hospital workers' contract negotiations will be more closely watched: If they were able to set a $20 hourly minimum wage at the state's largest private-sector employer, their contract would drive up wages elsewhere.

"It would reverberate around the state ... in terms of what other workers think is possible," said Steve Howard, executive director of the Vermont State Employees' Association, whose public-sector members do not have a similar pay guarantee.

The thousands of unionized employees AFT Vermont has added in recent years is notable in a state where only about 38,000 of 284,000 workers were represented by unions in 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Seven Days was able to identify only one other election, a lawmaker-enabled effort by independent home health workers in 2013, that was larger than the recent vote among hospital support staff. It allowed more than 7,500 workers to bargain with the state.

The hospital vote was also one of the larger private-sector election victories by a union anywhere in the country in recent years, according to Jonah Furman, who follows unions for the magazine Labor Notes.

Nurses at UVM Medical Center unionized in 2002, but attempts to add support workers over the past two decades never garnered enough steam to reach a vote, even as other classes of hospital employees continued to organize. Most recently, 350 or so resident physicians voted last spring to join an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

The pandemic reenergized the movement among support staff. Like nurses, they worked the front lines during a health care emergency that was compounded by a staffing shortage. They were celebrated as "heroes" during lockdowns, licensed nursing assistant Jordan Bushway recalled, but the praise has yet to lead to much material relief.

"I think we all looked at each other at this time and just said, 'Why are we not being treated like the health care heroes that we were being quoted as? Why are we not treated as so?'" Bushway said.

Pay for licensed nursing assistants starts at $17.36 per hour and tops out at $26.01 per hour, plus benefits, according to UVM Medical Center. Bushway, who works in the Mother-Baby Unit, said she makes about $22 per hour after seven years at the hospital.

Bushway and others on the union organizing committee said in interviews that inadequate wages are exacerbating the staffing shortage that has plagued UVM Medical Center and hospitals nationwide. Jacob Berkowitz, who assigns employees to various inpatient units each night in his role as a staffing office specialist, said difficult working conditions and low pay have affected morale.

"It's driving people out of the field," he said.

The union drive began in early 2022 and eventually amassed an organizing committee of 70 or so employees who reflected the diversity of the sprawling workforce. In addition to hundreds of nursing assistants and clerical workers, the unit also includes patient attendants, custodians, food service workers and others. It's one of the more racially and ethnically diverse workforces in the state; organizers translated their campaign materials into languages spoken by the Nepali, Somali, Congolese and other immigrant communities represented on the hospital's staff.

Their effort was aided by the Vermont Federation of Nurses & Health Professionals, which in its recent contract struck a deal with the hospital that limited how administrators could respond to future organizing drives. Both sides agreed not to "disparage" the other's "motive or mission," and management agreed not to hold so-called "captive audience meetings" with employees to urge them to vote no.

In a statement, UVM Medical Center president and COO Stephen Leffler said the hospital, which did not voluntarily recognize the union before the election, wanted to ensure that staff "had an opportunity to have their voices heard."

"We believe the election administered on-site by the National Labor Relations Board met that goal, and expect to be in contact with the union soon to begin negotiating in good faith a collective bargaining agreement," he wrote.

The election came at a time when the hospital has been pinched financially; increasing labor costs — particularly for a surge in temporary, traveling workers who were used to plug staffing shortfalls — were the biggest contributor to a $23 million operating loss at the hospital last year, officials have said.

Asked whether the employees' anticipated demand for $20 per hour was reasonable, a hospital spokesperson said, "Our goal is to compensate our employees competitively."

New union members are still fleshing out their list of requests, but those on the organizing committee said $20 reflects a more realistic minimum hourly wage in Chittenden County.

"They should be paying individuals livable wages where they can have a fulfilling life outside of the hospital," said Natalie Cartier, 26, a pharmacy technician who lives in South Burlington.

The cost of living in the Burlington area has risen rapidly since 2018, when Sen. Sanders publicly criticized the hospital for paying some employees less than $15 per hour. Many Vermont employers raised wages during the pandemic to attract workers in a tight labor market, though the state minimum wage is still just $13.18 per hour.

In response to Sanders' 2018 callout, which echoed the nurses' union's demand, UVM Medical Center officials said the hospital had to be careful when raising wages because of the pressure it would apply on other local businesses, Seven Days previously reported.

In Shelburne, the upscale elder community Wake Robin advertises a wage floor of $18.25 per hour, which it describes on its website as a way to support a "livable wage for all Vermonters" and enact its social values. Seven Days asked to interview one of the organization's leaders about the effect of hospital wages on how it sets pay; the organization responded with a statement through a public relations firm that said Wake Robin is "glad that we can offer the pay and benefits that we do."

Raising the wage floor at Community Health Centers of Burlington, a federally funded group of clinics, emerged as the consensus top priority among the 168 support staff who formed a union last May, according to Brandon Lawson, a medical assistant there. Following months of negotiation, CHCB management agreed to a $20 hourly starting wage beginning in August 2023, along with increased time off.

Lawson, who was a member of the bargaining team, described the negotiations as "very amicable." CHCB, which relies mostly on patient revenue and federal grants, has a tight budget, but "management was very clear with us that they want to do the best they can without sinking the organization financially."

"Everyone wanted the same goals," CHCB spokesperson Kim Anderson said. "It took a few months to figure out how to get there financially."

To raise the wage floor, the union agreed to smaller raises for members on the higher end of the pay scale, Lawson said. But, he added, it made sense to concentrate the biggest pay increases for the people at the bottom.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.