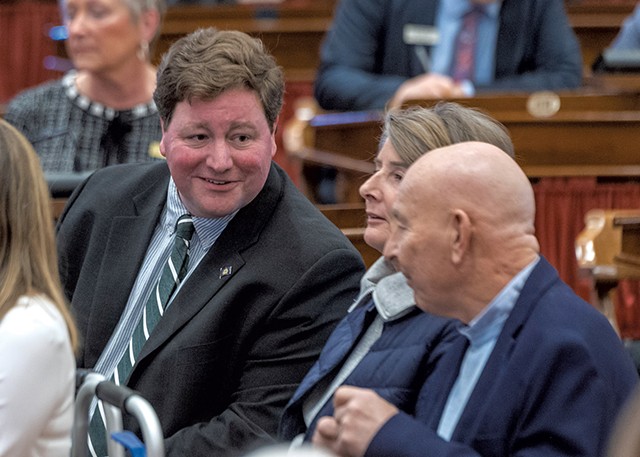

- File: Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Treasurer Mike Pieciak

Imagine if families on Medicaid, which provides health care to low-income people, could invest $3,200 on behalf of each newborn baby and leave the money untouched as the child grows.

After 18 years, the investment would be worth about $11,500 — and available to help that teen pay for school, a car or an apartment. If left alone to grow for another 12 years, the sum would reach about $24,500 — an economic boost for Vermonters in early adulthood.

That's the idea behind so-called baby bonds trust fund, a concept that Vermont Treasurer Mike Pieciak is promoting to level the playing field for young adults whose families aren't able to offer them financial support.

Baby bonds could be used to address what Pieciak sees as some of Vermont's biggest long-term challenges: generational poverty, rural economic development and Vermont's need to retain its people.

"We don't often focus on these long-term anti-poverty policies but more on what is happening in this business cycle, this election or whatnot," Pieciak said in an interview. "We have to get more into the long game across our society, broadly and in government."

The idea has received a warm reception in the legislature but no financial support. The concept has taken off recently around the country. Groups are working in several cities to create such programs, aiming to reduce homelessness and advance racial equity.

The University of Chicago's Chapin Hall policy research group has created a tool kit to help public and private groups start such programs. The group notes that many young adults do receive significant sums from their families when they are starting out. A 2020 Merrill report showed that 79 percent of U.S. parents extend financial help to their children while they are between ages 18 and 34.

Pieciak has made economic inequality the centerpiece of his position as treasurer since he was elected in 2022. He draws inspiration from the work of economist Darrick Hamilton, a professor at the New School in New York City who advocates for giving every low-income child up to $50,000 by the time they become adults. In an interview with New York Times journalist Ezra Klein last June, Hamilton described how wealth frees people to make choices such as moving to take a better job or turning an idea into a business. It also helps them withstand emergencies.

The top 10 percent of households own about 70 percent of all wealth, Hamilton said. While a salary is one way to generate income, earning money on investments — an option generally only available to the wealthy — has proven to yield great returns in recent years. While household income grew by only about 30 percent between 1989 and 2018, the S&P 500, a broadly diversified index of U.S. stocks, grew by about 400 percent.

"If you had just enough money that it could sit there in the S&P 500, it went up by multiples" in that time period, Hamilton said on Klein's podcast. "And you didn't really have to do anything new to get that at all."

Connecticut's treasurer, Erick Russell, is a believer. That state became the first in the nation to start a trust program for its Medicaid-eligible children last year. For each Connecticut child whose birth was covered by Medicaid after July 1, 2023, the state will invest $3,200. The money grows as the child does, and they can use it between the ages of 18 and 30 for buying a home in Connecticut, investing in a Connecticut business, paying for higher ed or job training, or saving for retirement. Participants must complete a financial literacy course.

Pieciak's idea is similar, with an investment of $3,200 on behalf of a Vermont baby eligible for Medicaid. About 2,000 babies are born under the state's Medicaid program each year, he said, so the investments would cost about $6 million a year.

More than 70 House members signed on to a bill that would create the program.

"In the long run, it would be a great investment," Rep. Mike Marcotte (R-Coventry) said. He's chair of the House Committee on Commerce and Economic Development, which took testimony on the proposal.

Cosponsor Rep. Rebecca Holcombe (D-Norwich) said the program would offer a valuable lesson in financial literacy. "It's not surprising the treasurer is so supportive of it," she said. "You can watch this small investment compound over time."

The committee voted unanimously on March 14 to support the program, and it's likely to win support in the Senate Committee on Economic Development, Housing and General Affairs, where chair Sen. Kesha Ram Hinsdale (D-Chittenden-Southeast) is the lead sponsor of a similar measure.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Celsi Pratt (left) speaking with Liz Scharf of Capstone Community Action

Such a program might have made a difference for Celsi Pratt, who said she dropped out of Spaulding High School two weeks before her class graduated nine years ago. She has spent the ensuing years in and out of several GED programs.

Now that her 4-year-old son has started school, Pratt, who lives in Barre, wants to show him that education matters, so she's taking classes in academics and personal finance through a high school diploma program run by Capstone Community Action in Barre.

Pratt's biggest priority is to secure a permanent home. She wishes she'd had some money for a down payment when she was 21, before real estate prices spiked.

"Even a little bit would have helped," said Pratt, 26.

A Vermont baby bonds program would need more than the approval of Marcotte's committee. In a tight budget year, the money to fund it is not available.

Pieciak originally proposed using funds from the state's unclaimed property division, which falls under the treasurer's office and provided $10 million to the state's general fund last year. The money usually goes to one-time expenses.

The House Commerce and Economic Development Committee asked Pieciak to find a different revenue stream — perhaps grants or donations — and the bill its members voted out had no identified funding source. Committee members also want Pieciak to add provisions that would encourage baby bond recipients to stay in Vermont; to invest the trusts in a way that increases housing opportunities; and to expand the financial coaching component.

Pieciak said he's going to start looking for revenue sources, and the program won't start this year.

"In a tough budget year, that's a good step forward," he said of the committee's support.

Gov. Phil Scott, too, feels this is not the year for the effort.

"He is supportive of the concept, but in a year that we have to prioritize wants versus needs, unfortunately we have to say no to a lot of interesting ideas for the time being, and that's why the Governor did not include it in his budget," his spokesperson, Jason Maulucci, wrote in an email.

The baby bonds wouldn't be the first program of this sort in Vermont.

Last August, Spectrum Youth & Family Services of Burlington started a program that gives 10 young people $30,000 each over the course of 18 months. The youths — chosen in part because they were homeless or at risk of becoming homeless — receive $1,500 a month, as well as access to a one-time payment of $3,000 to support large expenses such as a vehicle or move-in costs.

Mark Redmond, Spectrum's executive director, said caseworkers help the young people plan how to use the money. Most spend it on security deposits and rent, back rent or utility payments; classes; or transportation, he said.

It's not clear how well these programs work. In the developing world, where they've been in place for years, there are few conclusive findings. According to a 2021 research review by the World Bank, the programs are most effective at reducing poverty when used with other interventions, such as training in job and life skills.

But Redmond said he's confident in the concept.

"When you have some basic financial stability, you can make longer-term and better decisions about your life," he said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.