- Luke Awtry

- Dr. Kimberly Quinn'

As students arrived for Kimberly Quinn's 11 a.m. class in early September, she handed each a multicolored button that read, "Be the boss of your brain." During this semester, she aims to help them mold their young minds — literally.

A Champlain College professor and expert in cognitive and positive psychology, Quinn teaches students how to reprogram their brains to become happier, healthier, and more mindful and resilient in the face of adversities that range from anxiety and depression to chronic disease.

That day in the classroom, the 56-year-old New York native wore black-and-white Converse high-tops and splashy, rainbow-colored pants that set off her bobbed haircut and red-rimmed glasses. Quinn began the class — called Mindcraft: The Psychology of Optimal Human Functioning and Life Satisfaction— as she starts all of her lessons: with a one-minute silent meditation.

She then asked students to read from their gratitude journals. She requires them to spend several minutes each day jotting down at least three things for which they're grateful — an exercise popularized by University of Pennsylvania professor Martin Seligman, considered the father of positive psychology.

"It could be dad's banana bread, my golden retriever, my eyesight, my hot tea, whatever," Quinn told the class. Her hope is that, by semester's end, the students will be in the habit of noting such things. Quinn has done so for years.

Students listed what one might expect these mostly first-year college kids to be thankful for: their parents, their health, a favorite roommate, energy drinks, sleep.

Beyond the camaraderie such disclosures can inspire, Quinn emphasized that the exercise is based in neuroscience. Writing out the words "I am grateful for," she said, directs blood flow to the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which can be measured on a specialized MRI scan.

Stimulating the neural pathways associated with gratitude makes them stronger and more likely to fire, which confers many physical and psychological benefits. The primary one, Quinn said, is that the brain, which acts as a pattern-recognition machine, starts searching the environment for even more sources of gratitude.

This phenomenon, known as the Tetris Effect, was first discovered by studying chronic players of the video game, who began seeing its colored geometric shapes in the real world, Quinn said.

In as little as 21 days, she explained, students can effectively train their minds to find more reasons to appreciate things in their lives that they might otherwise overlook.

"Remember, it's not touchy-feely," Quinn emphasized. "It's neurological."

Quinn doesn't say that lightly. She knows firsthand how hard it can be to rewire one's brain. Quinn overcame childhood abuse inflicted by alcoholic parents, as well as an undiagnosed neurological condition, to become the healthy, upbeat person she is today. She worked for years as a therapist, earned a PhD in cognitive psychology and has taught at Champlain for a decade. In 2018, Quinn won the college's Francine Page Excellence in Teaching Award, given to one professor each year. She's been central to Champlain's efforts to teach everyone on campus — students, faculty and staff — how to be more mindful, grounded, playful and adept at managing their emotions.

The need for such skills has never been more urgent, because the pandemic exacerbates mental health issues that were already pervasive on college campuses. Quinn responded with a singular mission: to make everyone at Champlain happier and healthier.

The popularity of Quinn's Mindcraft course is a testament to her efforts. Since she launched the course four years ago, it's become one of the most sought-after on campus and consistently has a waiting list. Initially an elective, it became a requirement this fall for all psychology majors. Quinn is teaching three 15-student sections this semester, and every one is full.

She hopes to make the course a requirement for all incoming students. Laurel Bongiorno, Champlain's dean of the Division of Education & Human Studies, said that ambitious goal was under consideration.

"Kim can bring that knowledge and education into the classroom, whereas we [counselors] don't have that opportunity," noted Skip Harris, Champlain's director of counseling, student health and wellness. "We call Kim our secret weapon."

Defeating the 'Dark Arts'

- Luke Awtry

- Dr. Kimberly Quinn'

For years, Champlain, a small, private college of about 4,200 students, has described its offerings as "radically pragmatic." In addition to a mandatory core curriculum of academics, all students must complete the InSight Curriculum: four years of instruction in financial and career skills. These include managing personal finances, tracking one's credit history, negotiating a salary, building a résumé and assessing a potential employer's workplace culture.

Starting this fall with the class of 2025, Champlain added a new element to its life-skills mix: emotional and physical well-being.

"Across college campuses, especially small college campuses like ours, we're seeing a huge uptick" in demand for mental health services, said Harris at Champlain's counseling center.

Even before COVID-19, 60 percent of all U.S. college students reported feeling "overwhelming" anxiety, and 40 percent reported depression so severe that they had difficulty functioning, according to 2018 and 2019 data from the American College Health Association. Rates of suicidal thoughts, severe depression and self-injury among college students have more than doubled in less than a decade, the association reported.

Champlain has experienced those trends. As Harris noted, a year and a half of the pandemic and social isolation has amplified preexisting mental health concerns.

In a normal year, he said, Champlain's counseling center would see "just a handful" of students seek help before classes started. This year, Harris had 35 such requests.

Pre-pandemic, his clinicians wouldn't need to start a waiting list for appointments until at least six weeks into the semester. This year, the wait list started after the first week of classes.

In 2020, as the pandemic ramped up and Champlain halted all in-person instruction, Harris sought advice from Quinn, who had just taken on an additional role: campus-wide program coordinator for well-being and success. He asked her how they could get ahead of these trends and help students build more self-sufficiency.

Champlain's counseling center already had a robust program for triaging mental health calls, which allows students to see a counselor within 24 hours. Nationally, the average wait time on college campuses is seven days, according to 2020 data from the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors.

"Could I use five more counselors? Sure. Would they just get booked up? Yes. That's just the nature of the work," said Harris, whose center now has six counselors. "But what we're really trying to do as a community is to help our students become more resilient and better at managing their own discomfort."

In March 2020, when Champlain switched to all-remote learning, Quinn launched a weekly podcast to continue the training she couldn't do in person. Called "Mindcraft: Become the Boss of Your Brain & Live Your Best Life," it addresses topics such as the importance of smiling and laughing through difficult times, creativity and self-expression, mindful giving, healthy sex, and the sweetness of doing nothing. Though students are now back on campus, Quinn has continued the podcast; about half her listeners are located outside the U.S., in 55 countries.

- Luke Awtry

- Dr. Kimberly Quinn's hat

Quinn also writes a campus-wide newsletter, called the Mindful Times, and moderates weekly meetings of a club she has dubbed Defense Against the Dark Arts. The professor, who borrowed the club's name from J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series of novels and movies, shows up each week in her purple wizard's hat and gown.

Despite its name, the club has nothing to do with fantasy cosplay or nerding out on Hogwarts trivia. It's a support group during which Quinn offers tools and strategies to help students manage their anxiety, depression and feelings of unworthiness — aka the "dark arts." So why the Harry Potter theme?

"If you tell young adults that you're going to have a depression support group, do you think anybody's coming to that?" Quinn asked. Then she turned on a nasally New York accent: "'We're gonna have a depression support group in the Saint Jude basement. We'll have doughnuts.' Like, who's going to that? No one!"

Though the club includes some mindfulness training and "a splash of psych education," Quinn said, it's not an academic course. Rather, it's student-centered, spontaneous and fun. To that end, Quinn organizes extracurricular events such as Halloween pumpkin carvings and bonsai tree plantings. The wizard's outfit, she said, is just an outward manifestation of having fun with mental health.

At least once a year, Quinn dresses in a gorilla outfit and walks across campus just to see how many people notice her. This, too, serves as a lesson in mindfulness. Based on the famous "invisible gorilla" experiment, in which most test subjects failed to notice a person in a gorilla suit walking through a video, it demonstrates humans' proclivity for overlooking things that are right before our eyes.

Plus, Quinn loves incorporating play into her work whenever she can.

"Playfulness is so important," she added. "When [students] see seasoned grown-ups modeling playfulness out in the world, it gives them permission to hang on to that playfulness in themselves."

Hardship to Happiness

- Luke Awtry

- Dr. Kimberly Quinn in class

Quinn acknowledges that some of her positive worldview is the result of genetics — some people are just born with sunny dispositions.

"Kim has always had this really positive attitude, super high energy, wanting everyone to get along ... She's always been like that," said Lori Lillimagi-Boehm, Quinn's childhood friend and neighbor. The two women have known each other since they were 5 years old.

But one's environment and upbringing play critical roles, too. Quinn taught herself to find happiness in the darkest of places.

"Even though I have a happy-go-lucky temperament, it's a lot of work, because the world out there is constantly throwing curveballs," Quinn said. "There's a lot of choice making, and I choose to live deliberately."

Quinn grew up in New Paltz, N.Y., the elder of two daughters of alcoholics. Her father, who worked for an insurance company, sometimes disappeared for months at a time. When he was home, life was no better. Quinn described her childhood household as loud, chaotic and occasionally visited by the police. It wasn't uncommon for her to retreat to the rooftop with her friend to escape the chaos below.

"It was our thinking place," Lillimagi-Boehm recalled. "She kind of felt closer to God there, you know?"

Though Quinn did well in school and served as captain of her high school ski team, her accomplishments made little impression on her parents.

"My sister was the golden child, and I was their designated scapegoat," she said. "My father pounded the shit out of me."

At 16, Quinn started dating an 18-year-old boy who was good-looking and drove a fast car, which she described as "every parent's nightmare." Once, after the boyfriend got caught drinking alcohol, Quinn's father forbade her from seeing him. When Quinn protested, her father threw her headfirst into a dresser.

Quinn's mother was never formally diagnosed with a mental illness, but Quinn strongly suspects that she was bipolar. Once, her mother took her on a frenetic, hourlong drive to the Bronx, blaring loud music and speeding the entire way.

When they finally stopped at a diner, her mother explained how much easier her life would have been had her daughter not been born. In fact, her mother told Quinn that she'd originally planned to get an abortion but decided instead to do the baby "a favor," so Quinn should feel lucky to be alive.

At 16, shortly before the manic car ride, Quinn finally revealed to her mother that, from the age of 6 until her early teens, she had been sexually abused by a relative, who had threatened to hurt her if she told anyone. Upon hearing the story, Quinn's mother got up and then matter-of-factly went about her day, leaving Quinn feeling "dirty and worthless."

"I came home one day, and my mother had changed all the locks on the doors, and I couldn't get in," she said. By 17, Quinn found herself homeless and living out of her car.

In those days, she would often park her car on Mohonk Mountain near New Paltz, crack a window, lock the doors and pray. Her faith in God, she said, helped get her through some of the most difficult times. She wasn't raised to be religious, but her neighbor's Italian family was Catholic; when Quinn decided to join the church, Lillimagi-Boehm sponsored her conversion.

In 1983, while still in high school, Quinn told a guidance counselor that she wanted to attend a small college in Vermont where she could ski. He handed her a Saint Michael's College catalog, which featured a photo of a rainbow behind the Colchester Catholic school's chapel.

"Just looking at that catalog," she said, "I knew it was meant to be."

Quinn borrowed her uncle's old IBM typewriter and banged out a college essay. She then used money that she'd earned working as a lifeguard to pay the application fee. Despite her rocky relationship with her father, he agreed to cover her tuition.

"St. Mike's literally saved my life," Quinn recalled. "I cannot even imagine where I would be without it. The people there wrapped around me like a burrito, and because of this, I was able to soar."

At St. Mike's, Quinn discovered a sense of calm and inner peace. She was befriended by Father Michael Cronogue, the much-beloved late Edmundite priest. One day, Father Mike walked Quinn to the counseling center, where she later joined a support group for adult children of alcoholics.

Quinn also joined the school's cross-country team to stay in shape for the ski team but soon was more focused on running than skiing. The cross-country team, she said, "was the superglue holding me together.

"Honestly, I feel like these people were brought into my life," she continued. "I truly believe God brought me a ton of angels along the way. They mirrored the value in me that my parents did not, and I developed a very positive sense of self late in the game."

For years, Quinn tried, unsuccessfully, to reconcile with her family. Eventually, she severed all ties with her parents and sister.

"When they tell you they wish you weren't born, where do you go from there?" she asked. "So I released them like helium balloons."

While at St. Mike's, Quinn was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a condition she began to address in her forties. She also met her future husband, Tom Smith, at the college. Father Mike officiated at their wedding. They have five adult children, whom Quinn calls "the fab five."

While Quinn doesn't share her trauma stories in her college courses, she doesn't conceal them, either. As she put it, "I think secrets are toxic."

A High-Energy Gift

- Luke Awtry

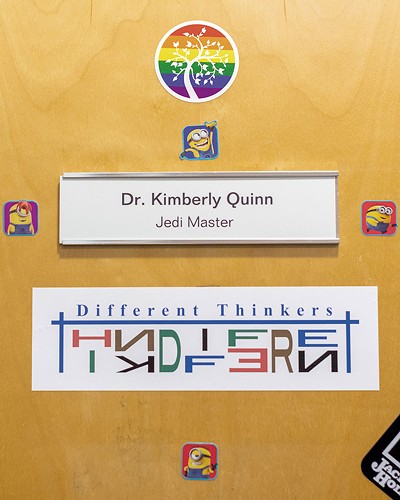

- Dr. Kimberly Quinn's office door

Adults have benefited from Quinn's positive-thinking guidance, too. Under the name Kimberly Quinn Smith, she has published three books: one on menopause, one on parenting teens and one on motherhood in general. She has also published two workbooks for professionals and more than two dozen articles in Psychology Today, and she has given two TEDx talks.

In one talk, Quinn shares her experience of growing up with undiagnosed ADHD, or "attention surplus high-energy gift," as she calls it. She worked as a therapist for much of the 1990s and bristles at the word "disorder." She never uses it in the classroom. But her euphemism for ADHD isn't a form of political correctness; it's about getting people to reimagine their innate weaknesses and strengths.

"Disorder," Quinn said, "is a shame word. It leaves us feeling less than and defective." Her own neurological condition, Quinn said, gives her an "enhanced ability for divergent thinking, creativity and innovation." She believes that her frenetic energy enabled her to write the three books, which, she said in her TEDx talk, flowed out of her "like water from a faucet."

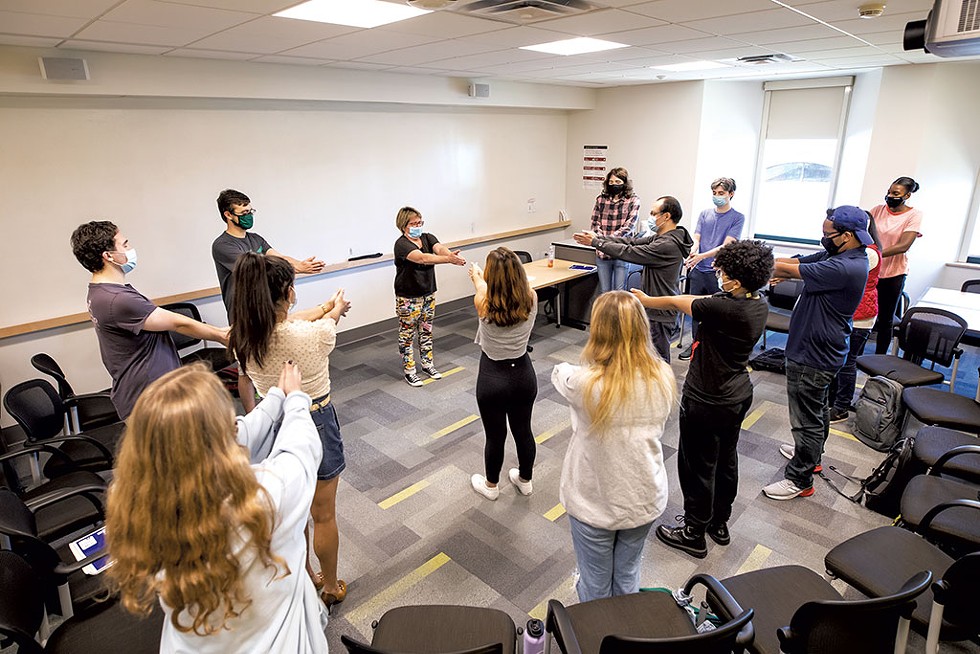

Quinn encourages a flow of ideas in her Mindcraft class, too, aiming to support students' freedom and expression. In the September class, where students sat in a large circle (Quinn abhors rows of desks), her energy was on full display. She practically vibrated with enthusiasm, pacing the floor like a motivational speaker.

Some students were chatty and outgoing; others were so quiet it was difficult to hear them speak through their face masks. But Quinn addressed each one personally, having committed their names to memory. Several students who've taken her class previously noted that she regularly referred to them as "rock stars" and "superstars."

In that class, Quinn was eager to share some of her so-called "party tricks" — simple massage exercises that stimulate the vagus nerve and temporarily deactivate the amygdala. The latter is the "fight-or-flight" part of the brain that reacts to dangerous or threatening stimuli, she said, as well as "the anxiety worry-circuit headquarters." Soon, all the students were rubbing their eyelids or massaging their earlobes in circular motions, temporarily deactivating their "anxious monkey mind."

In a 10-minute span, Quinn leapt from quoting Aristotle — "one of my favorite dead guys," she quipped — to showing a clip from the '90s sitcom "Everybody Loves Raymond" to explaining the role of dopamine in making humans treat each other nicely.

Dean Bongiorno said that when she encounters students who are struggling with anxiety or who aren't performing well academically because of emotional challenges, she often recommends Quinn's Mindcraft class. Bongiorno remembered suggesting it to one student, who returned at the end of the semester just to thank her.

Quinn recalled another student, a game design major, who enrolled in Mindcraft by mistake. He'd misread the course title and assumed that it was about the online video game Minecraft. Despite his error, the student not only stuck with the class, Quinn said, but became one of her most active participants that semester.

Alyssa Johnston, an 18-year-old first-year student from Weymouth, Mass., took Quinn's Mindcraft course over the summer. It was her first college class, so she had no idea what to expect, especially because the class was taught remotely.

"When Dr. Quinn started doing these meditation exercises, I was like, What am I doing here? This isn't what I signed up for," she recalled.

After the first class or two, however, Johnston decided she was into it.

"Not to be cliché," Johnston said, "but she's an inspiration to me because she's a very positive person, and positivity is something I've struggled with over the years. I definitely look up to her."

Nathaniel Slade, a senior from the Northeast Kingdom who's studying business administration and marketing, also took Mindcraft over the summer. He called Quinn "one of my favorite teachers ever. She's super energetic, and you can definitely tell that she's passionate about well-being and teaching it to other people."

Slade particularly enjoyed learning about gratitude journals, a practice he's continued and now swears by.

"It definitely does work," he said. "After a couple of weeks or so, you start seeing things randomly that you're grateful for. You're driving along, and something will suddenly just pop out at you, and you're like, Wow!"

It's Not 'Happy-ology'

- Luke Awtry

- Dr. Quinn leading a breathing and mindfulness exercise in class

For other students, Quinn's course provided lessons whose impacts transcended the typical college-level stressors of midterm exams and first job interviews.

Reid Anctil, a 23-year-old psych major from western Massachusetts, took Quinn's class in the spring of 2018. (At the time, it was still called Positive Psychology.) Later that summer, just weeks before he was due back on campus, Anctil was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He missed a year of school while undergoing chemo, radiation and recovery.

Quinn's course dramatically altered his mindset toward his cancer.

"I was able to find some of the silver linings in it," he recalled. "Most people wouldn't say anything positive about a cancer experience, but ... I've had some incredible experiences because of how it's changed my outlook."

Anctil doesn't deny that he experienced fear, sadness, anger and frustration. As Quinn often told her class, positive psychology is not "happy-ology."

But through the class, Anctil said, he learned to differentiate between events that happen to us and how we interpret them. It also taught him that his cancer didn't define him.

"It's about me moving forward and not just being stuck in 'Woe is me. This is the worst. My life is over,'" he explained. "It's about acknowledging [the bad times] and then putting them aside and moving forward."

Ultimately, Anctil had a positive outcome: In December 2018, he was declared cancer-free and has suffered no permanent side effects from his brain tumor.

Dr. Andrew Rosenfeld has no firsthand knowledge of Anctil's case, nor is he an oncologist. But Rosenfeld wasn't surprised to hear that Anctil's positive mindset was helpful during his cancer treatment and recovery.

Rosenfeld is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine and clinical director of child psychiatry at the Vermont Center for Children, Youth and Families. In addition to his clinical and research duties, Rosenfeld teaches an undergraduate class at UVM similar to Quinn's, called Science of Happiness.

Though the neuroscience of happiness, gratitude, mindfulness and optimism is relatively young compared to most other disciplines, when it comes to their effects on healing and recovery, Rosenfeld said, "the literature is quite striking."

Rosenfeld cited a research study that began in the 1970s. Called the Nurses' Health Study, it's considered one of the largest investigations ever conducted into the causes of major chronic diseases in women.

In the early 2000s, Rosenfeld said, as thousands of nurses in the study reached retirement age with higher risks of mortality, researchers began dividing them according to their levels of optimism, determined through questionnaires. Even after accounting for other factors such as smoking, diet, exercise and alcohol consumption, the study found that nurses with the highest levels of optimism had at least a 10 percent lower chance of dying. The most striking reduction, Rosenfeld noted, was in infectious causes, in which there was a 50 percent reduction in mortality.

These findings, Rosenfeld added, align with other studies on mindfulness and positive emotions.

One study published in the March 2016 issue of the peer-reviewed journal NeuroImage compared the brain scans of subjects who spent three months doing gratitude writing exercises, such as those Quinn leads in her Mindcraft class, to those who did not. After three months, the subjects were given a "Pay It Forward," or altruism, task to perform while in an fMRI scanner.

The study found that three months of simple gratitude writing was associated with "significantly greater and lasting neural sensitivity to gratitude." This resulted in behavioral improvement in the subjects, all of whom were being treated for anxiety and/or depression.

Rosenfeld noted that the benefits of positive thinking can be measured from the behavioral level down to the cellular level. A positive mindset, he explained, reduces the body's inflammation response; too much inflammation damages cells and is linked to many diseases, including cancer. A positive mindset can also affect the body's ability to produce antibodies after vaccines, a critical factor in the midst of a global pandemic.

Quinn didn't set out on her current path to save lives. While at St. Mike's, she considered pursuing a career as a physician but couldn't decide whether to become a cardiologist or a brain surgeon.

Ultimately, she switched to cognitive and positive psychology, a field that, in a sense, can heal both the heart and the mind. If she can help students lead healthier, happier lives through training their minds, that's enough.

"Our valuable life minutes are really all we have," she said. "What else is there?"

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.