- Luke Awtry

- Manon Belzile

In Manon Belzile's glass-walled office at Beta Technologies, a dry-erase board displays the words: "I don't want to be bothered with limits." The quote, Belzile said, is hers. "Or shoes," she added, glancing begrudgingly at her wizened Blundstones. "I would also rather not be bothered with shoes."

In a perfect world, she explained, she would go straight from sandals to ski boots, with nothing in between; her goal, in life and at Beta, is to optimize efficiencies of both the mechanical and existential variety. Belzile, 51, answers to sundry titles at the South Burlington electric aviation startup: According to the official org chart, she's vice president of propulsion; she also goes by "VP of Radness" and, on Slack, "Motor Ninja." But at Beta, with its Silicon Valley-esque nonchalance about such formalities, Belzile defines herself solely by her work. And her work, literally and figuratively, drives the company forward.

Her all-consuming preoccupation: building the lightest and most powerful motor that can safely propel Beta's signature electric aircraft, Alia, up to 250 miles, at cruising speeds of 170 miles per hour, while carrying a payload of up to six passengers, or the equivalent in cargo. To that end, Belzile and her team of 28 engineers spend their days in feverish pursuit of the simplest effective configuration of magnets and copper wire, the main components of the motors commonly used in today's electric vehicles. Once they've hit upon a potential winner, they subject it to a battery of tortures — scorching it, freezing it, frying it with voltage of lightning-like intensity — to determine its ruggedness.

In the nascent field of jet-fuel-less aviation, Beta has already cleared some significant regulatory hurdles. Last year, the Federal Aviation Administration gave the go-ahead for Alia to begin flight tests over Plattsburgh International Airport; in the spring of 2021, Alia became only the second electric aircraft approved for airworthiness by the U.S. Air Force. Meanwhile, major companies have been placing bets on Beta's continued success. In April, the company inked a deal to sell at least 10 Alia planes, at roughly $4 million a pop, to United Parcel Service by 2024; United Therapeutics, whose CEO, Martine Rothblatt, put up $1.5 million to help founder and CEO Kyle Clark launch Beta in 2017, has requested 60 aircraft to be delivered by 2026 to transport the synthetic human organs the biotechnology firm plans to manufacture.

- Courtesy Of Brian Jenkins/Beta Technologies

- The Alia aircraft

But the path to commercial certification, which Beta needs in order to make good on those commitments, is far from clear-cut. "We believe in our motors, but the FAA will need to be convinced," said Belzile. "And they have no experience with electric motors, so we have to generate all the data to back them up." By her estimate, producing enough data to assure the FAA of Alia's safety could take up to three years.

In one of Beta's design laboratories, a gleaming, glass-encased room with a unicorn stenciled on the door, Belzile showed off a dummy of the rotor currently being used in Beta's two Alia planes, which rested in a hangar about a dozen yards away like bony, prehistoric beasts. Over the inescapable din of machinery, she extolled the virtues of the rotor — a wreath of magnets inside a metal ring, about 21 inches in diameter, that looks a bit like a specialty cake mold.

"This goes into a motor that develops nearly 500 horsepower and weighs not even 100 pounds," she said. "The motor in my Tesla weighs three times that." The animating principle of Beta's aircraft, Belzile explained, is minimalism: "We only add metal where we need it, as opposed to thinking from the outside in, which is how the other guys do it — starting with the structure, and adding on and on."

Belzile, who lives in Fairfield, worked in the aviation industry for the first 11 years of her career — first at Pratt & Whitney, then at a gas turbine manufacturing company in California. In late 2018, she had just left her job as an engineering specialist at Husky Injection Molding Systems in Milton, the local arm of an Ontario-based company that makes plastic parts for a mind-numbing array of everyday objects.

"I wasn't having all that much fun anymore, and it was looking like it was going to be a really great winter," said Belzile, who wakes up at 4 a.m. most mornings during the ski season to squeeze in at least one run down Smugglers' Notch or the Underhill side of Mount Mansfield. When she told one of her coworkers at Husky, Brandon White, that she was devoting herself to the full-time pursuit of ski bumming, White showed her a Seven Days article about Beta, then just a year old, and its pursuit of cleaner aviation.

"He said, 'I don't believe you,'" recalled Belzile. "'This is where you're going.'"

That winter, Belzile applied herself to the self-assigned task of skiing 150 days. But, as White had predicted, she soon got bored. She toyed briefly with the idea of designing and selling ultra-efficient weed cultivation systems, but ultimately, she said, "I decided that was just not going to be very helpful for humanity." As a winter sports fanatic, she was more deeply concerned about the environmental impact of fossil fuel-guzzling technologies. She remembered the conversation she'd had with White about Beta, so she submitted her résumé, even though the company had no listed job openings. Within a couple weeks, Belzile had a meeting with Clark, the founder and CEO.

Clark told Belzile that Beta needed someone who could design an inverter, which supplies motors with electrical current. Belzile explained to Clark that she'd never done that before. "He told me, 'It's mostly a thermal problem,'" said Belzile. "And I said, 'Ah! I know thermal problems. I can do that.'" In the spring of 2019, Belzile became Beta's 25th employee. (White, her former Husky colleague, came aboard shortly thereafter; the company has since grown to 300 employees and counting.)

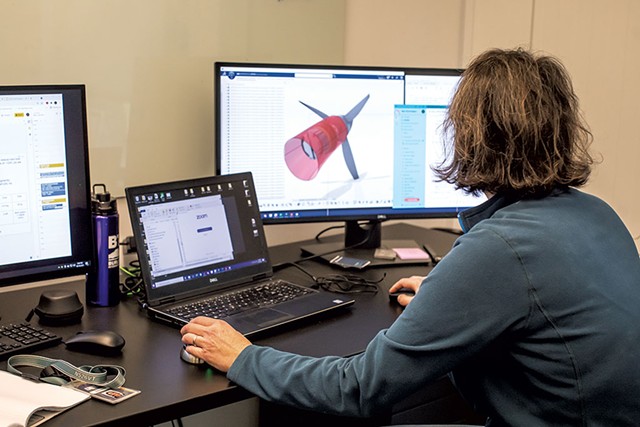

- Luke Awtry

- Manon Belzile working on designs

Wesley Grove, Husky's chief operating officer, believes that Belzile's particular combination of engineering prowess, single-minded determination and impatience for bureaucracy makes her an ideal fit for Beta. "She's not afraid to share her mind, and she's generally right, which doesn't always go over well in corporate America," said Grove. "But Beta is run organically, with a very flat structure, and everybody's just doing what needs to be done to make the project go forward. And I think it really suits her well."

Her confidence, he added, allows her to tackle engineering problems that would intimidate other people — for instance, figuring out how to keep Alia's motors cool during flight, which is crucial to the safety of the aircraft. "It's a real problem that aerospace people haven't solved," Grove said, chuckling. "And there's Manon, working on it."

There is an unmistakable air of competitiveness about Belzile, the kind of self-possessed intensity that comes from having a complete working knowledge of your physical and psychological limits. Belzile, who grew up in New Brunswick, Canada, represented her country in women's track cycling at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul; for eight years, she and her husband, John, a chemist, lived on a sailboat off the coasts of Connecticut, Los Angeles and San Francisco. (Their two children, now 17 and 18, spent their toddlerhoods at sea.) When Belzile was learning to fly one of Beta's helicopters — free flight lessons are a standard Beta perk — a pedal malfunctioned, causing the craft to spin wildly. By some combination of luck and skill, Belzile managed to regain control and land safely.

"My philosophy is that I'm going to extract myself out," Belzile said. "And if I cannot extract myself out, well, too bad for me."

- Luke Awtry

- Motor attachment on Alia

In fact, Belzile has extracted herself from far worse. In December 1989, when she was studying mechanical engineering as an undergraduate at Montréal's École Polytechnique, a man armed with a Ruger and a hunting knife entered a second-floor classroom and ordered the women and men to stand on opposite sides. After declaring that he was "fighting feminism," he opened fire on the women.

Belzile, who was in class on the sixth floor, mistook the gunshots for celebratory firecrackers, an end-of-the-semester antic for École Polytechnique seniors. She and her classmates took the escalator downstairs to see what was going on; as they approached the third floor, she saw someone bleeding on the ground.

"That's when we were like, 'Holy shit,'" Belzile said. As she got off the escalator and made her way toward the exit, she came face-to-face with the gunman. The thing about having a gun pointed at you, she explained, is that the brain can't assimilate the facts; it feels dreamlike, unreal. "My bag was full, and I should have thrown it at him or kicked him in the nuts," Belzile said. "But I didn't think like this. I just ran." As she sprinted away, he fired after her, shattering the glass walls along the corridor.

Miraculously, Belzile made it around a corner and out an emergency exit, unhurt. It was 5:30 in the evening, already dark, and a light snow was falling. Later, after she'd gotten home, she noticed a bullet hole in the cuff of her boots. When she opened her backpack, she discovered that another bullet had pierced the outside pocket, tearing through a pencil case and two books before lodging itself in her differential equations textbook, just inches shy of her back. Fourteen people were injured and 15 died in the massacre, including Belzile's rock-climbing partner, a woman named Anne-Marie Edward.

Surviving that experience seems to have given Belzile a newfound freedom, a kind of memento mori that helps her bypass much of the bootless worrying that incapacitates other people. "I wouldn't say I feel invincible," said Belzile, "but I do feel that shit is going to happen, and I might as well have fun. Because if I can't have fun, what else am I going to do?"

And fun, for Belzile, means perpetual motion. This summer, a shoulder injury kept her from rowing on the pond near her house, so she learned how to ride an e-foil, an electric surfboard that cruises on a tail wing above the water's surface. E-foiling, she said, makes her feel weightless, as if she's in flight.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.