- File: Brooke Bousquet

- Camel's Hump summit

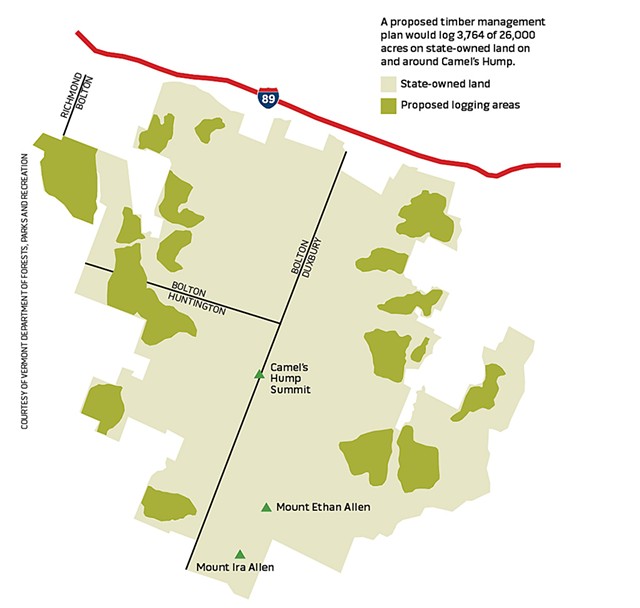

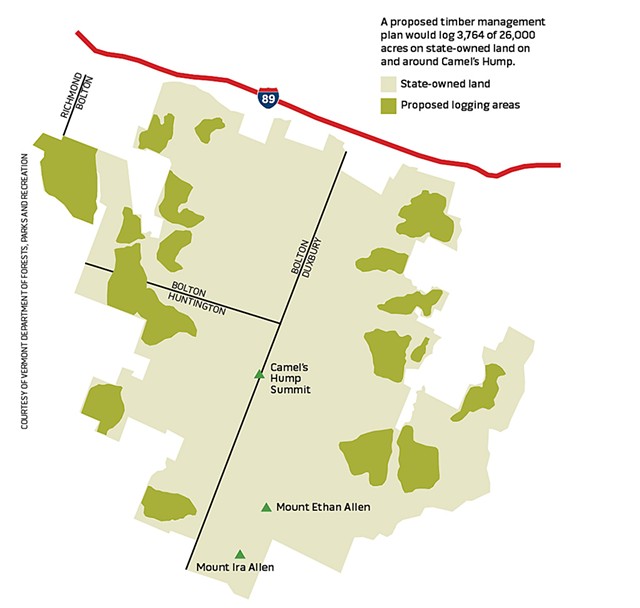

Opponents of a plan to harvest timber from nearly 3,800 acres of mature state forest around Camel’s Hump are calling for a logging moratorium there.

Standing Trees, a Montpelier-based forest-preservation group, argues that the 15-year logging plan for the area fails to account for benefits such as flood prevention, carbon storage and clean water that come from not cutting down trees.

Logging is scheduled to begin this year on about 340 of the 26,000 acres of public land around the state’s third-highest peak. So the group says time is of the essence.

“This is desecration of a landscape that is of incredible importance to Vermonters,” said Zack Porter, the group's executive director.

Camel’s Hump is such an iconic part of Vermont’s landscape that it is effectively “our center of gravity” and deserves protection not just for residents but for the plants and animals that call it home, he said.

In a petition delivered to state officials Tuesday, the group demands that the Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation adopt clear rules for the management of state forests. The group’s attorney, James Dumont, argues that the state is required by law to adopt formal rules for logging on its lands, but has failed to do so.

A 391-page “long-range management plan” for the area passed in 2021 analyzes the logging envisioned, but not in as detailed or as transparent a way as required by the state's formal rule-making process, Dumont said.

The group said it is giving the state 30 days to respond to the petition, which 38 people signed. The law requires agencies to adopt formal rules when at least 25 people challenge an informal written state policy, according to Dumont.

In his letter to Snyder and other state officials, Dumont asks the state not to approve contracts for timber sales in the area until the rules are adopted. He also asks that no sales be allowed until tracts can be assessed for the presence of the endangered northern long-eared bat.

According to the management plan, lands around Camel’s Hump are presumed habitat for the bat, one of five that is either endangered or threatened in the state. The bat’s populations have plunged due to white-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease that strikes the animals as they hibernate.

The logging plan requires officials to consider the potential impact on bats and to adjust projects accordingly. But Dumont argues that’s not good enough for bats whose populations have plunged by 90 percent in some places and are listed as endangered by Vermont and threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.  Field studies are needed to ensure bat habitats aren't harmed, and whenever that's unavoidable, loggers should have to get special “taking” permits, Dumont wrote.

Field studies are needed to ensure bat habitats aren't harmed, and whenever that's unavoidable, loggers should have to get special “taking” permits, Dumont wrote.

The group argues that Vermont has failed to consider the climate impacts of logging. Letting trees age is a potent climate change solution, and there is little indication the state studied the carbon impact of the logging, Porter said.

“There is a higher and better use for state lands in 2022,” he said. “This is a logging project that looks like something we would have seen 50 years ago. It’s time to get with the times.”

It’s been five years since public input was taken on the plan. Since then, the climate crisis has worsened, extinction of species has accelerated globally, and the state has passed legislation requiring emission reductions, he noted.

Jamison Ervin, a Duxbury resident and Standing Trees member, said logging reduces the land's ability to absorb heavy rainfall like the kind that devastated the state during Tropical Storm Irene.

Jamison Ervin, a Duxbury resident and Standing Trees member, said logging reduces the land's ability to absorb heavy rainfall like the kind that devastated the state during Tropical Storm Irene.

Dirt roads and aging bridges will also suffer from the strain of 500 million pounds of logs being hauled out of the forests, with no funds earmarked for road improvements, said Ervin, a forest management consultant and member of the Duxbury Selectboard.

In her view, that state seems to view public land management through the lens of logging, she said, when land conservation as a natural climate solution is most needed.

“We’re dealing with an agency that has not yet really come to grips with the role of forests and soils in our carbon equation," Ervin said.

Standing Trees, a Montpelier-based forest-preservation group, argues that the 15-year logging plan for the area fails to account for benefits such as flood prevention, carbon storage and clean water that come from not cutting down trees.

Logging is scheduled to begin this year on about 340 of the 26,000 acres of public land around the state’s third-highest peak. So the group says time is of the essence.

“This is desecration of a landscape that is of incredible importance to Vermonters,” said Zack Porter, the group's executive director.

Camel’s Hump is such an iconic part of Vermont’s landscape that it is effectively “our center of gravity” and deserves protection not just for residents but for the plants and animals that call it home, he said.

The long-range management plan for the area that state officials approved in 2021 calls for logging 251 acres per year — more than triple the average number of acres logged for the past 25 years. The cutting is slated to occur in 35 different sections of Camel’s Hump State Park, Camel’s Hump State Forest, and the Huntington Gap and Robbins Mountain wildlife management areas.

In a petition delivered to state officials Tuesday, the group demands that the Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation adopt clear rules for the management of state forests. The group’s attorney, James Dumont, argues that the state is required by law to adopt formal rules for logging on its lands, but has failed to do so.

A 391-page “long-range management plan” for the area passed in 2021 analyzes the logging envisioned, but not in as detailed or as transparent a way as required by the state's formal rule-making process, Dumont said.

The group said it is giving the state 30 days to respond to the petition, which 38 people signed. The law requires agencies to adopt formal rules when at least 25 people challenge an informal written state policy, according to Dumont.

Mike Snyder, commissioner of the Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation, said he appreciates the public interest, takes seriously any concerns about the management of public land and timber harvesting, and would respond officially to the petition soon.

“We need a little time to digest it,” Snyder said.

While he welcomes open, fact-based conversations about forest management, Snyder said, he feels the petitioners are misguided to focus on timber harvesting rules if what they’re really after is a way to completely block logging on public lands.

Vermont law clearly grants his department the authority to sell timber on state lands, he said. The group's interpretation of the rule-making requirements appears to be the result of statutory "cherry picking," he contended.

The bigger question, he said, is why people would want to block responsible local timber harvests if that leads Vermont to import more wood products from elsewhere.

“We’re being elitist when we export our massive need for wood products elsewhere in the world while we protect our little green paradise here,” Snyder said.

“We need a little time to digest it,” Snyder said.

While he welcomes open, fact-based conversations about forest management, Snyder said, he feels the petitioners are misguided to focus on timber harvesting rules if what they’re really after is a way to completely block logging on public lands.

Vermont law clearly grants his department the authority to sell timber on state lands, he said. The group's interpretation of the rule-making requirements appears to be the result of statutory "cherry picking," he contended.

The bigger question, he said, is why people would want to block responsible local timber harvests if that leads Vermont to import more wood products from elsewhere.

“We’re being elitist when we export our massive need for wood products elsewhere in the world while we protect our little green paradise here,” Snyder said.

In his letter to Snyder and other state officials, Dumont asks the state not to approve contracts for timber sales in the area until the rules are adopted. He also asks that no sales be allowed until tracts can be assessed for the presence of the endangered northern long-eared bat.

According to the management plan, lands around Camel’s Hump are presumed habitat for the bat, one of five that is either endangered or threatened in the state. The bat’s populations have plunged due to white-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease that strikes the animals as they hibernate.

The logging plan requires officials to consider the potential impact on bats and to adjust projects accordingly. But Dumont argues that’s not good enough for bats whose populations have plunged by 90 percent in some places and are listed as endangered by Vermont and threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Courtesy of the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation

Earlier this month, after Gov. Phil Scott vetoed a bill that would have required the state to conserve 30 percent of its land and waters by 2030, Porter vowed his group would "up the ante and play hardball" to protect forests. Standing Trees has also called for a moratorium on logging in the Green Mountain National Forest.

The group argues that Vermont has failed to consider the climate impacts of logging. Letting trees age is a potent climate change solution, and there is little indication the state studied the carbon impact of the logging, Porter said.

“There is a higher and better use for state lands in 2022,” he said. “This is a logging project that looks like something we would have seen 50 years ago. It’s time to get with the times.”

It’s been five years since public input was taken on the plan. Since then, the climate crisis has worsened, extinction of species has accelerated globally, and the state has passed legislation requiring emission reductions, he noted.

- Taylor Dobbs

- State forester Jason Nerenberg inspecting a forest in 2018

Dirt roads and aging bridges will also suffer from the strain of 500 million pounds of logs being hauled out of the forests, with no funds earmarked for road improvements, said Ervin, a forest management consultant and member of the Duxbury Selectboard.

In her view, that state seems to view public land management through the lens of logging, she said, when land conservation as a natural climate solution is most needed.

“We’re dealing with an agency that has not yet really come to grips with the role of forests and soils in our carbon equation," Ervin said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.