- Rob Donnelly

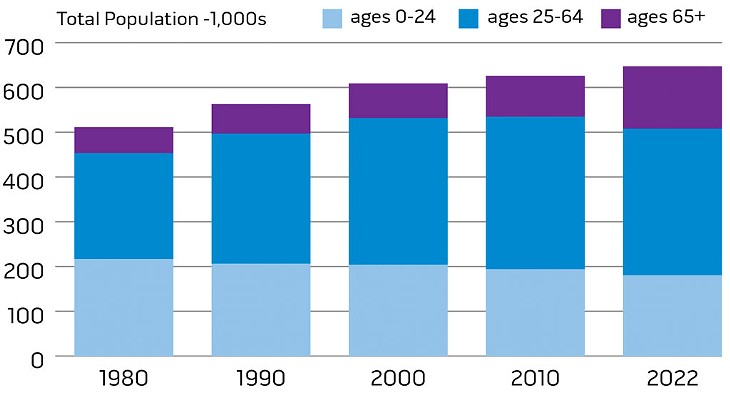

Vermont is aging rapidly. Its median age has jumped from 37 to 43 in just two decades, making it the third-oldest state, behind only Maine and then New Hampshire. The number of Vermonters 65 and older has nearly doubled over that same period. They now outnumber children and, by 2030, will comprise close to 25 percent of the population.

About this series

In This Old State, Seven Days will report throughout 2024 about the implications of Vermont's aging population. This is the inaugural story in the series.

Got a tip or feedback? Write to us at [email protected].

These demographic shifts, while long fodder for political speeches, have never captured the public's attention, their implications vague and seemingly distant amid more immediate crises. But the effects of aging on this small state have become impossible to ignore — and will only become more consequential in coming decades.

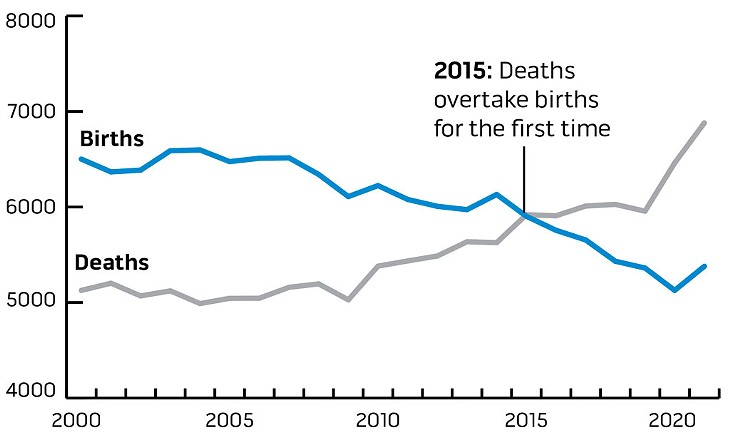

More people are dying than are being born, a gulf that has widened in the eight years since Vermont first crossed that tipping point. The state's population is projected to shrink in the coming decades as those of most other states grow, which will have profound impacts on every aspect of life.

Vermont's population can be visualized as an hourglass, with the biggest bulges reflecting college students, more than half of whom go on to leave the state after graduation, and the retirement-age baby boomer generation. Between them is a narrower waistband representing people of working age.

251 Shades of Gray

Fewer young people in the workforce will make it harder to replace retiring workers and could imperil the overall growth and competitiveness of the state's economy. That will put the squeeze on state finances at a time when more seniors need support.

The full dimensions of this situation and the challenges that result could take years, if not decades, to reveal themselves. But the shifts are already being felt. For example, Vermonters are facing wrenching decisions over how much residents are willing to pay to maintain local public schools with shrinking student bodies.

The shift will also have deeply personal ramifications. More elderly people will live alone, often in rural areas in houses ill-equipped for residents with flagging physical abilities, and more families will face difficult decisions about how to care for relatives.

It wasn't long ago that Vermont's demographic outlook appeared quite different. A key destination of the back-to-the-land movement, the state was once growing faster than the rest of the country, with some 70,000 people settling here in the 1960s and '70s. A subsequent baby boomlet contributed to a consistent period of growth.

But the trend didn't last. Vermont's migration gains tapered off around the turn of the century as the allure of rural life waned and an economic downturn sent young people flocking to cities. Meanwhile, fertility rates, which began falling as women gained more access to education and contraception, dropped further as anxieties mounted over climate change and the financial burden of raising a child.

Vermont's rural areas have been harder hit by this one-two punch, laying the groundwork for a stark rural-urban divide when it comes to the effects of an aging population. While Vermont has gained some 40,000 people since 2000, the vast majority have settled in the northwestern part of the state — mainly, the greater Burlington area.

Only Chittenden and Franklin counties recorded more births than deaths in 2021. Meanwhile, Bennington and Orleans counties reported twice as many deaths. Some towns, such as Ira and Norton, now go years without welcoming a new baby.

Foreseeing this, state leaders have spent years trying to lure more people, especially young families, into Vermont. But that has done little to slow the trend. Beyond a one-year jump during the pandemic, when rural Vermont became a popular alternative to large cities, the state's population has plateaued over the past decade. Last year, after accounting for deaths and people who left the state, Vermont gained a net of only 92 people.

Vermont isn't the only place grappling with these changes. Countries in Europe and Asia have been confronting shrinking, aging societies for years. The United States as a whole is also experiencing a declining birth rate. But while other regions have offset those losses with a massive influx of immigrants, New England has not.

Vermont and a handful of its neighbors will thus be navigating this demographic future without a road map of tested strategies. Our experience will inform the rest of the nation.

Aging in Rural Places

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Eleanor Ahlers of Hyde Park grocery shopping with the help of Joan Greene of Lamoille Neighbors

As an avid snowmobiler in the 1970s, Robert Spaulding would ride past a small cabin in the backwoods of Corinth and think to himself: I'd like to own that place one day. Two decades later, he opened the Washington World, a weekly newspaper in Berlin, and saw the property was for sale.

My dream came true, he thought. He bought the cabin, fixed it up and, after his divorce in 2011, moved in.

Now 76, Spaulding is finding it harder to maintain his slice of paradise. Weed-whacking his sloping lawn is more of a chore after four hip surgeries. The 40-pound bags of wood pellets seem to be growing heavier. And the dirt road that leads to the camp has become so muddy recently that he's decided to stay at his son's home in Barre this week, lest the road become inaccessible.

"Age has got me to the point that I can't take care of everything I got," he said.

Most seniors want to age in place, meaning outside of an eldercare facility, surrounded by family and friends. But in Vermont, suitable arrangements can be hard to find.

The state's housing stock is among the nation's oldest, meaning many homes will need major upgrades to be considered age-friendly: ramps, shower bars, wider doorways to accommodate wheelchairs. Seniors on fixed incomes may struggle to afford these fixes, and contractors can be difficult to find.

Vermont's lack of affordable senior housing leaves few options for people who no longer want to worry about maintaining their homes. Cathedral Square — which owns and manages affordable housing for older adults in Chittenden, Franklin and Grand Isle counties — has a waiting list of two to five years. The organization could double its current portfolio of 1,100 units and still barely meet the existing need, to say nothing of tomorrow's.

Among those on the waiting list are some 200 people who own single-family homes in Chittenden County. Getting them into new housing would free up their homes for others — young families, perhaps.

"A lot of people are stuck," said Greg Marchildon, director of AARP Vermont.

Green Mountain State geography poses its own challenges. Country life may have its allure, but rural seniors can struggle to get around. Vermont has a lot of dirt roads, and driving skills can ebb with age. Those who make the difficult decision to give up their car keys find few reliable transportation options.

"They look around and say, 'Well, how am I going to get to the store? How am I going to go see my friends? How am I going to see my grandchildren? How am I going to get to a doctor's appointment?'" Marchildon said.

Isolation is a big risk for rural seniors, especially those without family nearby. A quarter of Vermont's 65-and-older set lives alone. Some are housebound and rely on the help of others to get by.

Nonprofits strive to bring social connection to seniors through programs such as Meals on Wheels. As a volunteer with the Northeast Kingdom Council on Aging, Jeannine Richards, 77, spends time with vulnerable seniors on a weekly basis. Some, she said, simply want to play cards or watch TV. Others need to be roused from bed at 2 in the afternoon.

"When we interact with these people, we get the full breadth of the human condition," she said.

As of 2021, roughly 135,000 people 65 and older lived in Vermont. Of that group:

81%

owned their own homes

26%

lived alone

21%

were in the workforce

Among those trying to make the best of their twilight years is Eleanor Ahlers, a 94-year-old who raised five children in Vermont; only two still live in the state. "When we sat down at a table for the holidays, we had maybe 30 or 35 people," she said. "Now we're lucky to have five."

She, too, left for a time, living in a Massachusetts town where everything she needed was within walking distance. She now lives on her own in a mobile home in Hyde Park.

Ahlers manages to get out quite often, despite no longer driving. She goes out to eat with her daughter, who lives in Morrisville. She recently participated in a creative writing class and attends potlucks at a local park.

With the help of a volunteer-driven nonprofit known as Lamoille Neighbors, she also still does her own shopping. Every Wednesday, someone picks her up and takes her to the store.

Her goal: to stay out of a nursing home.

"I'm fighting the fight," she said.

No Experience Needed

- Oliver Parini

- Andy Buxton running the front counter at Buxton's Store in Orwell

Andy Buxton grew up in his grandparents' general store in Orwell. He cut meat, stocked shelves and catered to a cast of colorful customers, including some who would bring in broken appliances in the beds of their pickup trucks for his grandfather to fix. So when a businessman who purchased the store from his grandparents wanted out several years ago, Buxton jumped at the chance to buy back and revive the family biz.

He borrowed $100,000 to build a commercial kitchen and crafted a menu of "fancy-ish" foods, from flatbread pizza to baked fish to roast beef sandwiches. He also bought a $30,000 ice cream shack. The upgrades were a hit in the small, rural Addison County burg, especially among the wave of second-home owners who moved there during the pandemic.

What Buxton hadn't anticipated was how difficult it would be to keep it all running. For the past two years, he's been desperately trying to hire cashiers and deli workers, with little success. He eventually had to cut back hours and shutter the kitchen.

"It used to be a rite of passage for any young person in the village to work at Buxton's," he said ruefully.

The little store is one of many Vermont businesses affected by a chronic labor shortage that shows no signs of abating. Vermont's unemployment rate of 2.2 percent is among the lowest in the country. Employers had more than 17,000 open jobs in December — more than twice the number of people estimated to be actively searching for work.

Many of these open jobs are in sectors vital to the state's future: construction workers to build new housing, health care workers to care for the elderly. A lack of workers also strains restaurants, bookshops and country stores that dot Vermont's landscape — signature places unlikely to return once they're gone.

The tight labor market has benefited workers, forcing companies to raise wages and benefits to compete for employees. Vermont's lowest wage earners experienced a 4 percent increase in pay over the past few years, even after accounting for inflation, according to the Public Assets Institute, a Vermont think tank.

But the tight labor market has also made it harder for companies to grow. Citing a labor shortage at its cut-and-wrap facility, Cabot Creamery recently had to temporarily discontinue some of its products, including its hefty three-pound blocks of cheese. (They've since returned to shelves.) In Rutland, a wave of retirements has forced the 70-year-old manufacturing company Carris Reels to shift production to its out-of-state plants occasionally.

As they scramble for workers, companies are increasingly looking to train people they might have otherwise overlooked in the past: those with criminal histories, in recovery from drug addiction or lacking experience.

Companies once looked for workers with at least minimal experience, said Tyler Davis, vice president of enterprise sales for ETS, a recruitment firm that works with manufacturing companies in Vermont. Now, anyone with "a basic familiarity with hand tools and a reliable car" can get a job.

The shrinking workforce could impact Vermont's bottom line. More than half of the state's general fund comes from taxes on personal income, which typically falls when people retire. If the jobs that baby boomers leave can't be backfilled, that could lead to a gap in state revenue, making it harder to cover the growing costs of state-funded benefits such as Medicaid and pensions. Covering those costs with less money coming in would require the state to either raise taxes or cut spending.

The longer the labor shortage lasts, the harder it will be for businesses such as Buxton's to stick it out. "I planned to be here until I'm 65, 70, and pass on the legacy," said Buxton, who's 43. "Now, I don't know."

Last week, during a lull in the lunch rush, a local resident walked in with his young daughter, who had won "student of the month" at Orwell Village School. The reward, courtesy of Buxton's, was a free ice cream cone. But the shop owner had bad news: "Sadly, our ice cream shack is gone," he told the girl. Unable to staff the machine, he had sold it.

She chose a premade dessert from the cooler.

Old Schools

- Oliver Parini

- Buxton's Store in Orwell

More than 100 kids once attended Lakeview Elementary School in Greensboro. Now, all seven of its grades could fit in a single classroom. Enrollment is so low that, when crafting Valentine's Day cards for a local nursing home last month, students had to make extras; the 30 elderly residents outnumbered the 27 card makers.

Many Greensboro voters don't want to lose their school, despite its dwindling enrollment. But residents in neighboring Hardwick, a town in the same district with its own elementary school, recently circulated a petition to force a vote on whether to keep Lakeview open. It's just too expensive, they argued.

Nowhere has Vermont's demographic shift been felt more than in its public school system. Enrollment has shrunk by more than 30,000 students over the past three decades. The precipitous decline, coupled with sharply rising costs, is reviving conversations about whether the state simply has too many small schools.

"We have a foot in the past and a foot in the future," Jeff Francis, executive director of the Vermont Superintendents Association, said in a legislative hearing last month. "We've really wanted to hang on to small schools as the center of every community and, at the same time, make sure that we have robust opportunities for every child in the state."

Vermont has been trying for more than a decade to rein in the cost of education. A landmark law known as Act 46 enacted in 2015 aimed to reduce administrative costs through school consolidations. Dozens of districts have merged since, but the cost of teaching Vermont kids remains among the highest in the nation — and is rising still. School districts have proposed budgets this winter that would raise Vermont's education spending by some $230 million, resulting in an estimated 19 percent average property tax increase statewide.

Adding to the financial stakes, many schools were built in the '50s and '60s to accommodate the baby boom and now face growing maintenance needs. A new report estimates that just bringing Vermont's school buildings up to par over the next two decades could cost $6 billion.

The bleak financial picture is pressuring districts to become more efficient. One of the quickest ways to do that is to close schools.

The Agency of Education, for its part, has no public position on how many schools Vermont needs, saying such decisions are up to individual districts. But expecting the volunteers who sit on school boards to take on difficult closure decisions on their own "isn't fair," Rep. Peter Conlon (D-Cornwall) said.

Conlon, chair of the House Education Committee, served on his local school board when it proposed closing one of its elementary schools a few years ago — unsuccessfully, it turned out. Unless state officials and lawmakers take a bigger role in those discussions, Conlon sees only two likely outcomes.

"Either we accept our school system across Vermont the way it is — expensive and not necessarily always providing the best opportunity for kids," he said, "or we go the difficult route of towns and school districts wrestling with [these questions on their own], often pitting neighbor against neighbor, community against community."

In Greensboro, David Kelley is one of many residents who want to keep the elementary school open despite its low enrollment — no matter what voters in Hardwick think. Why else would families consider moving into town? Of closing a school, he said: "You're writing your town's epitaph, in a way."

Sharing the Caring

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Adrianne Scucces pushing a wheelchair at the home in Barre Town where she cares for her 97-year-old mother

If Vermont's health care system came in today for its annual physical, an array of worrisome symptoms would be apparent. Overstretched ambulance crews unable to keep up with rising call volumes. Hospitals and nursing homes spending millions on temporary workers just to keep their doors open. Long wait times for appointments. Soaring costs.

This, too, is a workforce story. Vermont does not have nearly enough doctors, nurses, EMTs and home health aides. The shortage worsened during the pandemic as health care workers burned out and left for other fields. Those still in the trenches are only getting older. Half of Vermont's nurses are over 48 years old. One in three primary care doctors is over 60.

Vermont's aging population will further pressure the system. That could make it harder for the state to fulfill the promise that it seeks to give its older residents: choices in how they want to age.

Seven out of 10 people will require long-term care at some point in their lives, according to federal estimates.

For some, that means a home aide will come by to help them complete their daily activities: getting out of bed, dressing, eating, bathing. Others with chronic health conditions might need a nurse who can administer medication and perform physical therapies.

Vermont has tried to build this system in an effort to keep people out of long-term care facilities. But home health agencies say the cost of doing business greatly exceeds what government insurance programs are willing to pay.

Sara King, CEO of the VNA & Hospice of the Southwest Region, told lawmakers last month that her agency ran a $2.3 million deficit last year, largely because its revenue comes from those government plans.

"All of us home health agencies in the state are losing money," she said. "And it's really not sustainable."

A recent state-commissioned report found that none of Vermont's home health agencies is meeting all of its targeted hours, and some haven't fulfilled even 75 percent.

"We hear from lots and lots of people who don't have nearly enough services to be able to safely be in their homes," said Kaili Kuiper, an attorney with Vermont Legal Aid who serves as the state's long-term care ombudsman.

"We want people to be able to have a choice on how they're going to live their lives in their later years," she added, "but that choice is being taken away because it's so hard to stay in your home."

People who decide they can no longer live on their own run into their own set of challenges.

Long-term care is expensive: The average cost of a room at an assisted-living facility in Vermont runs about $5,000 a month, with some charging upwards of $10,000.

Medicare does not cover those stays over long periods, and Medicaid, the state-run program, is only available to those who are low-income, forcing people to effectively bankrupt themselves to qualify.

Vermont's patchwork of long-term care facilities is also greatly understaffed. Nursing homes have been relying on armies of travel workers, and a third have received emergency state funding over the past few years.

"We're really in a triage situation right now," said Helen Labun, executive director of the Vermont Health Care Association, an industry trade organization.

As homes get overwhelmed, the quality of care suffers. Kuiper said the longest-serving member of her team has reported a worrisome increase in the number of wound-care deficiencies at Vermont nursing homes.

Short-staffed homes are also more likely to discharge difficult patients against their will. Some older Vermonters wind up blackballed from every nursing home in the state, according to the Office of Public Guardian, and an increasing number of people are now landing out of state, hours away from family.

Capacity is its own issue. Vermont has lost access to some 500 nursing home and assisted-living beds in recent years because of closures and staffing shortages. That has made it harder for hospitals to discharge patients.

One day in January, the University of Vermont Medical Center had 83 such patients, representing more than a quarter of its medical beds.

"Some will wait days, weeks, months — or, shockingly, more than an entire year — for the right care setting with the right supports," wrote Stephen Leffler, the hospital's president and chief operating officer, and Christine Werneke, the president and COO of the UVM Health Network's Home Health & Hospice agency, in a press release last week. The backlog has "devastating" ripple effects, they wrote, leading to overcrowding and longer wait times at the emergency department. They called on the state and federal government to increase funding for the long-term care system.

As it becomes harder to find or afford care, a greater burden will fall to families.

Some 30,000 Vermonters are already providing care to a spouse or relative living with Alzheimer's or another dementia-related illness, a responsibility that has profound ramifications, from financial hardship to declines in their own physical and mental health.

This informal network provides about 36 million hours of unpaid care annually, according to state estimates, for a value of more than $700 million.

Adrianne Scucces, 71, has been providing care nonstop for the past few years — first for her partner, Tom, who died from ALS last year, and now for her 97-year-old mother, who moved in with her after a health scare.

While her mother is still sharp mentally, able to beat Scucces to the answers when they watch "Wheel of Fortune," the elderly woman needs help with daily activities such as getting dressed and bathing. Scucces is managing on her own so far. "I know when I'm pushed to the edge from previous experience," she said. But even if she wanted respite, she's not sure where to find it. A neighbor who helped out with Tom is now tied up with her own familial caregiving duties.

Caring for her mother has led Scucces to think more deeply about her own future as she gets older. With no children, she worries about what will happen to her when she can no longer take care of herself. It's a conversation she's had with other caregivers, she said.

"All of us in that position are wondering, Who's going to do this for us?"

Calling All Flatlanders?

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Eleanor Ahlers of Hyde Park going grocery shopping with the help of Joan Greene of Lamoille Neighbors

Kevin Chu has an ambitious plan to reverse Vermont's demographic slide: growing the state's population. A lot.

Chu is the executive director of the Vermont Futures Project, a nonprofit supported by the Vermont Chamber of Commerce that has spent the past two years spreading a pro-growth message. The goal: boost Vermont's population by some 200,000 by 2035, just over a decade away.

That's a tall order for a state whose population has grown by less than 50,000 since the turn of the millennium. But there's reason to think Vermont could attract more newcomers in the years ahead.

It has been viewed as a potential climate haven, and while last summer's record floods dampened that image, Vermont is still more attractive than many other places. The pandemic-era rise of remote work and the investment in rural internet is also allowing more people to consider small-town life.

Recent state efforts, such as the expansion of childcare subsidies and the now-expired Worker Relocation Grant Program, have also tried to make Vermont a more attractive landing place for families.

Chu thinks Vermont could also do a better job of retaining its young people. Only about 45 percent of Vermont's college graduates stick around after graduation, among the lowest rates in the nation. For starters, Vermont needs to change the "self-sabotaging" narrative that people need to leave to be successful, Chu said.

"I can understand why that story emerged again a decade ago when there were more people looking for work than work available," he said, "but the narrative hasn't evolved to match the conditions of the state."

Some factors, particularly housing, do limit Vermont's ability to grow.

Employers say applicants routinely turn down job offers after fruitless house searches. And testifying before the legislature last week, the directors of Vermont's two refugee resettlement programs said the rising cost of housing has made it hard to secure long-term placements for their new arrivals. That has forced them to reduce the number of people they're placing this year. In some areas, such as Burlington, established new Americans have found opportunities working in the eldercare sector.

State government is now pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into housing construction. But the capacity needed to meet Chu's vision is years off.

As Vermont looks for ways to influence its demographic shifts, efforts are under way to help adapt to the realities of a fast-aging state.

Last month, after a two-year process that featured input from dozens of senior groups and advocates, state officials published the Age Strong VT Plan, a 60-page report that serves as a road map for how Vermont can become more age-friendly.

The plan lays out a long list of objectives that mainly revolve around keeping seniors more active, healthy and financially secure. And it offers specific strategies for how the state can achieve these goals, with the help of communities, businesses and families.

For example, the plan proposes expanding digital-literacy programs for people over 55 to boost the number of older Vermonters in the workforce. It also calls for expanded capacity in the long-term care system and more funding for home health services.

Jane Catton, CEO of Age Well Vermont, contributed to the plan and described it as a good starting point. But knowing what to do and doing it are two different things.

"There's a lot of investment that has to go into our state to make us ready for the next five, 10, 20, 30 years ahead," she said.

Waiting for the day that these gradual, tectonic shifts begin to impact the lives of ordinary people will be "too little, too late," Catton said.

In many areas, however, that day has already arrived.

How did we become This Old State?

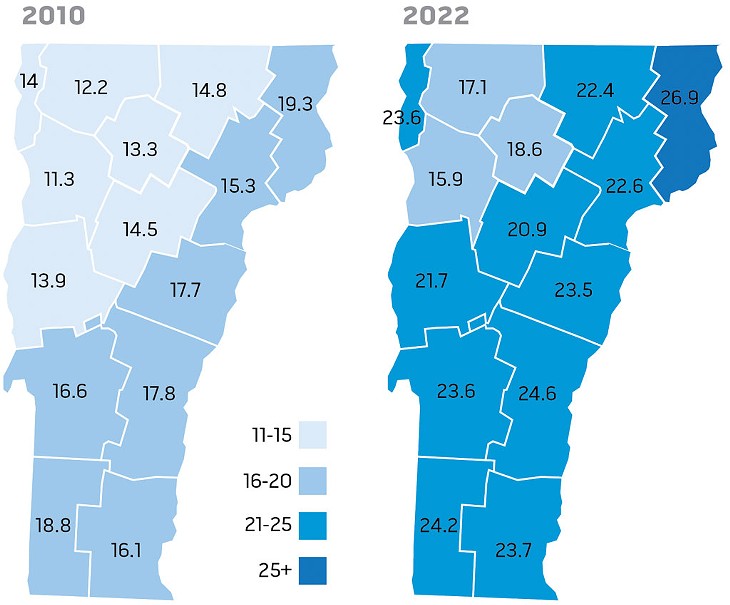

Vermont's median age is 43.2 — the third oldest in the country, behind Maine's and New Hampshire's. The population continues to grow older, and by 2030, one in three Vermonters will be older than 60.

County By County

- Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Vermont Department Of Health, Vermont Agency Of Human Services

Vermont's population is aging more quickly in places such as Essex County. This shows recent growth in the percentage of residents age 65-plus.

Birth and Death Rates

- Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Vermont Department Of Health, Vermont Agency Of Human Services

Vermont crossed the more-deaths-than-births threshold in 2015

Work Force

- Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Vermont Department Of Health, Vermont Agency Of Human Services

The share of working-age Vermonters, ages 25 to 64, was about 54.5 percent in 2010 but dropped to 51.1 percent in 2020 and then fell again in 2022 to 50.5 percent.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.