- Courtesy of Champlain College

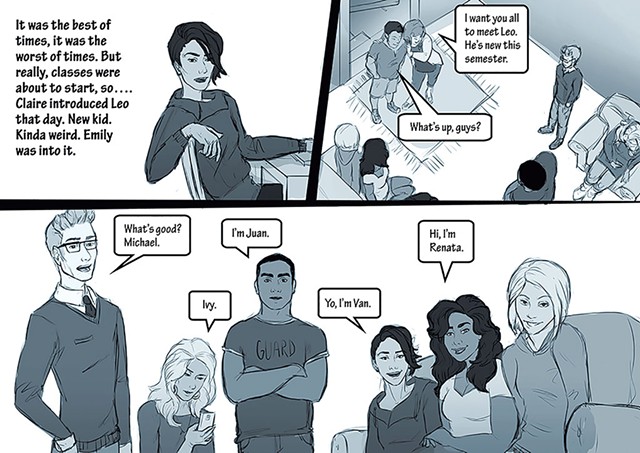

- A comic panel from the Make a Change game

Leo has his eye on Emily, a pretty blond college sophomore. They've gone on one date, but he hasn't heard from her since, despite texting her repeatedly. When he mentions his predicament to Michael, his friend has a suggestion to get Emily's attention: Send her a dick pic.

Leo, Emily and Michael are fictional characters in a new online game from Champlain College that addresses a tough subject: sexual assault and harassment.

Called Make a Change, it follows a group of sophomores from a dorm room to an awkward date to a booze-filled party. Playing the hourlong game feels like reading a graphic novel, with mini challenges embedded in the narrative. Last spring, Champlain's Office of Student Life began using it to educate students about sexual misconduct — taking an unconventional approach to what's become a pervasive issue on college campuses nationwide.

In recent years, student activists have criticized various schools for ignoring the problem of sexual assault. The Obama administration, too, has been prodding colleges to do more. Much of the attention has been focused on how these institutions investigate and adjudicate sexual assault cases. But increasingly, people are also demanding more comprehensive college prevention programs.

Such initiatives, required under federal law, often follow a similar script. Freshmen listen to a lecture, read some material online, maybe watch a skit. Champlain College, a 2,200-student private school known for offering innovative majors such as digital forensics and game design, provides those kinds of activities, too. Its first-years attend a safety talk that addresses sexual assault; the college posts information in its residence halls; and it recently launched what it calls the See, Say, Do Campaign to bring attention to the importance of bystander intervention.

Amanda Crispel, assistant dean for game development at Champlain College, wanted to do more. "The cohort of students that are in game development are primarily male, and we do have instances of sexual harassment," she said during an interview last week.

The gaming industry overall has a reputation for sexism and misogyny. Most notoriously, hackers harassed Zoë Quinn, Brianna Wu and other high-profile female gamers in a 2014 campaign known as Gamergate, sharing nude photos of them online, distributing their personal information and making death threats against them.

Crispel said she became even more eager to address the issue after a student who had been raped — by someone not affiliated with the school — sought her counsel. When Crispel discussed her concerns with staff at the Office of Student Life, they had a suggestion: Make a game about it.

"Initially, I was terrified and said, 'No, that's crazy,'" Crispel recalled. "It's a really, really difficult topic to make a game about. I wasn't certain that we could make a game that was approachable and that would engage people but wouldn't offend people."

But Crispel agreed to give it a try. It took three years to develop Make a Change, and a number of students and staff pitched in. They worked in Champlain's Emergent Media Center, which is equipped with software and prototyping tools — laser and vinyl cutters, 3D printers, a sophisticated-looking sewing machine — for creating interactive media, games and mobile apps.

As they sketched out the plot and began designing the game, they wrestled with how to make it entertaining without trivializing the issue.

Crispel and her team chose not to sanitize the content. The game opens with a trigger warning that alerts players to be prepared for vulgar language, sexual assault and emotional abuse.

The narrative is told through comic panels, drawn by students using Photoshop. They're black and white, which gives them a foreboding feel. Emily is the protagonist, and Leo, who is new to the school, starts pursuing her right away. Things get weird on their first date, when he starts texting her when she's using the restroom. Emily stops responding to Leo's entreaties but stops short of telling him she's not interested.

At the end of the date scene, the player enters a mini-game called Digital Defense.

The goal is to connect icons, which represent homework and other tasks, into chains — the longer the chain, the more points. Distracting the player throughout: Leo's benign but relentless text messages keep popping up on the screen.

It's one of several ways in which Make a Change addresses the relationship between technology and harassment.

In another challenge within the game, the player determines whether or not Leo's behavior toward Emily qualifies as sexual harassment. Leo, who opted not to send that dick pic, barely avoids crossing that threshold.

During another side game, the player has to arrange the characters in an apartment in a way that satisfies them all. It's like solving a puzzle, but instead of pieces, there are college kids, with different desires.

Make a Change culminates with a rape. The crime is implied but not depicted, and it's unclear at first who the perpetrator is. "We used a little bit of a soap opera technique in that you want to have a little bit of mystery," Crispel explained. But they were careful not to overdo it. "The goal isn't to shock," she said. "It's not like watching 'CSI.'"

Information about where to access support resources, what constitutes sexual harassment and why bystander intervention is important is woven throughout the game's main narrative and its mini-challenges.

Last spring, the Office of Student Life introduced Make a Change to students. Groups of them played together in their residence halls. Some loved the platform; others didn't engage at all, according to Danelle Barube, director of residential life. This fall, they offered it to freshmen during the first week of school, when the risk of sexual assault is highest. It wasn't mandatory, but about 200 of them played. "I think that says a lot," she said.

According to Barube, several students "have come forward to a campus resource and said, 'After I played, it made me rethink an experience I had, and now I think I need to get in touch with some sort of support resource, because I'm questioning what happened.'"

Champlain officials stress that they don't consider the game a "silver bullet" or even a stand-alone tool. After students play, staff lead a discussion about it. "I think Make a Change is us attempting to utilize that platform to start a really important conversation that some students would potentially not engage in otherwise. It creates this other entry point," Barube said.

Online games come with another advantage: Because the experience is active, as opposed to passive, "you experience it in your brain in many ways like it's an actual event," Crispel said. As a result, the content is more likely to have a lasting impression.

Nikki Pito, a senior studying game art, was one of several artists who drew the characters in Make a Change. She couldn't recall what kind of sexual-assault education she received as a freshman. It wasn't until playing Make a Change last year that she understood the range of support resources available to students. "I've been lucky enough that I haven't needed to look into them while I've been here, but I wouldn't have known anything otherwise," she said.

Pito said collaborators could opt out of being listed in the credits at the end of Make a Change, in case the game caused a backlash. She kept her name in and hasn't heard from any offended classmates.

On campus last Monday, earbud- and backpack-wearing students walked to and from class. Asked if they'd played the game, responses ranged from "What's Make a Change?" to "I think I saw some posters about it" to "I probably should."

One trio of juniors — two female, one male — had played it. "People had been talking about it, and it sounded kind of sketchy. I was like, 'There's no way a school handled this properly,'" said Tatiana Princivil, a digital forensics major who wore bright red lipstick and a slouch beanie. She continued, "So I played it, and it wasn't bad."

Robin Shafto, a computer science major who was holding her computer to her chest, said she is glad to see the college stepping up its sexual assault prevention efforts: "This game represents a really solid effort."

But they all agreed it could be improved. "It wasn't that exciting," said Christian Fusco, a computer science major who wore a hoodie and a baseball cap. "There were parts that were really easy to do."

As a resident adviser, sophomore Olivia Lyons played Make a Change with a group of freshmen this fall. "I heard some people making fun of it," Lyons said. But she noticed that the game-design majors got into it. "It started a conversation," she said, noting that of the 20 people who played that day, 19 were male. Lyons said she thinks Make a Change has potential as a prevention tool, pointing out that "a lot of kids won't go listen to a speaker."

Crispel and her team are applying for a grant to study the efficacy of the game.

With more schools paying attention to sexual assault, it's easy to envision Make a Change spreading to other campuses. But Champlain isn't releasing Make a Change to the public at this point — it's still in beta-testing on the school's student portal — and is mum about future plans for the game.

In the meantime, Crispel wants to make it more relatable for a wider range of people, by adding protagonists who are male, transgender, lesbian, multiracial and so on. Said Crispel: "This is a story about the human condition, not just about one particular sexual orientation or one gender."

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.