- Courtesy Of Tom Murphy

- Tom Murphy with his daughter Claudia

For any kid who's ever been picked on, Tom Murphy might seem like a real-life superhero. Their first introduction to him, in his standard middle-school presentation, begins with a video montage of the former mixed martial arts expert and star of Spike TV's "The Ultimate Fighter 2" kicking, tackling and pummeling various opponents into a bloody mess, all to the guitar licks of Creed's "Higher."

This bare-chested bruiser, with a shaved head and a torso dripping sweat and blood, has come to their school to teach students how to stop bullies? It seems too good to be true.

Moments later, Murphy jogs into the auditorium — head still shaved but now wearing black slacks, a pink dress shirt and each fingernail painted a different color — and floors his young audience with an unexpected confession.

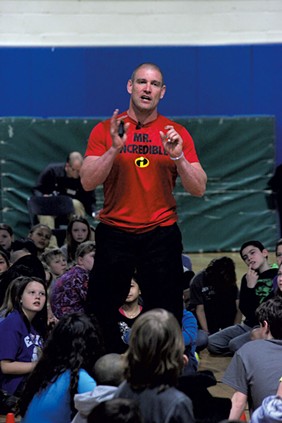

- Matthew Thorsen

- Tom Murphy speaking to fourth and fifth graders at Thomas Fleming School in Essex Junction

"I hate fighting," Murphy announces to several hundred students at Williston Middle School, using what's become his signature line about differentiating between contact sports such as MMA and hate-fueled violence. "There's nothing that I find more despicable on the planet."

And with that hook, the 6-foot-2, 240-pound powerhouse owns the kids for the next 90 minutes. In a video recording of that March 2015 event, they watch him, rapt, as he paces the floor with the restless energy of a caged panther while delivering a simple but powerful message: Everyone has the inner power to protect others from bullies. Murphy's task is to teach them how to "spring into action" — not by fighting, but by tapping a different form of courage.

Murphy suggests that every student at Williston Middle School, like kids at almost every school in America, could probably name two or three classmates who regularly get picked on, as well as who is responsible. Even in our current climate of "zero tolerance" for harassment, hazing and bullying, he says, most of the time the bullies get away with it. Every school has three groups of kids: those who get bullied, those who do the bullying and — the vast majority — bystanders, who are key to solving the problem.

"The world is a dangerous place," Murphy says, quoting Albert Einstein, "not because of those who do evil, but because of those who look on and do nothing."

So the 41-year-old St. Albans resident, restaurateur and father of four is doing something about it. Since 2011 he's delivered his presentation, called "Sweethearts & Heroes," to more than 1 million students, educators and parents nationwide — including to more than 20,000 in the last two weeks alone.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Tom Murphy speaking to fourth and fifth graders at Thomas Fleming School in Essex Junction

Murphy's mission: to make his "ABCs of anti-bullying" as universally known among kids as the "Stop, drop and roll" campaign is to fire safety. He's doing it by recruiting an army of school-based "heroes" who will stand up to tormenters.

"We've taught 50 million students what to do when they catch on fire, for the 135 who actually die every year in fires," he explains later in an interview. "The real reason kids don't jump into action to stop bullying? We've never taught them what to do! We say, 'Stick up for that kid.' But what does that mean?"

At 4 p.m. on a Friday afternoon in March, he spelled out his action plan to several hundred fourth and fifth graders at Thomas Fleming School in Essex Junction. A is for: Get the bullying victim away from the situation. B is for: Become the victim's buddy and show you care. And C is for: Confront the bully. Murphy reassured his young listeners that bullies rarely turn their aggression on the interloper, as they prey on those who are small, weak or different in some way. The key to success, Murphy added, is to act fast — typically within the first 10 seconds.

The Fleming School assembly, which omitted the mixed martial arts highlight reel, was Murphy's second of the day. At 8 a.m. that morning he gave the longer, edgier version of "Sweethearts & Heroes" to several hundred middle schoolers at nearby Albert D. Lawton Intermediate School.

ADL principal Laurie Singer says she invited Murphy to speak because of a series of recent bullying incidents that, "in my 10 years at ADL, I haven't seen before." She didn't elaborate. But her school learned the hard way that bullying can't be ignored. Ryan Patrick Halligan was a student there prior to her tenure. After his classmates cyber-bullied him relentlessly with homophobic taunts, he took his own life in October 2003, at the age of 13.

'Now I Know What to Do'

- Matthew Thorsen

- Tom Murphy speaking to fourth and fifth graders at Thomas Fleming School in Essex Junction

Such victimization is tragic and all too common. Every year, 100,000 kids drop out of school and never return. Another 170,000 routinely skip school because of mistreatment from their classmates. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for youth 10 to 24, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with an average of 5,400 suicide attempts occurring every day.

"Thousands of young people take themselves out of this world forever, and bullying helps them do that," Murphy says. "Most of the time, it's the final thing that pushes them over the edge."

Murphy and his business partner, Jason Spector, a physical-education teacher and coach in South Glens Falls, N.Y., have studied antisocial behavior, drawing from research at Yale, Princeton and Rutgers universities, as well as their own experiences. Spector himself lost four students to suicide, including one of his wrestlers. His and Murphy's partnership began in college, when they wrestled together at the State University of New York's College at Brockport.

The two often invite Rick Yarosh, a retired U.S. Army sergeant and Iraq War veteran, to join them. In September 2006, Yarosh's Bradley fighting vehicle was hit by a roadside explosive, and he sustained burns to over 60 percent of his body. Together, the three men deliver a potent lesson to students about overcoming adversity and accepting people who look different from them.

Yarosh and his service dog, Amos, joined Murphy at ADL. He was in Williston, too, where he told the kids of a tough encounter in a restaurant not long after his release from the hospital. Upon seeing his scars, a little girl halfway across the room stopped dead in her tracks.

When Yarosh said "Hi," the little girl turned around and darted back to her grandfather, who had urged her to introduce herself. Initially, Yarosh was frustrated and dismayed — until the girl turned to her grandfather and said, "Grandpa, he's really nice!"

"This 5- or 6-year-old girl changed my life," Yarosh said. "More importantly, she saved my life. How? By giving me hope."

According to Singer, the feedback about "Sweethearts & Heroes," from students and faculty alike, was "incredibly powerful," and Murphy was "swamped with kids afterward." Several told Singer they "needed" to tell him their own story personally; a few were so moved by the assembly that they had to spend time with guidance counselors to work through their emotions. Murphy also convened several smaller groups of 20 to 30 kids.

"I probably could have found 60 more students who wanted to spend another hour with Tom," Singer adds.

Murphy's website features five pages of similarly glowing testimonials, not just from educators but also from business professionals — he and Spector give motivational talks in corporate settings, too.

But the most important feedback Murphy gets is from the students themselves. During his recent 20-day tour of schools in Hawaii, he spoke to thousands of teens, many of whom belong to the island's indigenous population, are poor and suffer from various forms of discrimination. After one such presentation, a middle school girl handed him an unsigned, handwritten note that read: "I just wanted to thank you for taking time out of your day to come and teach us on making a better change in our school. I know it seems like no one cares, but I do. And so do my friends. This could change the world."

"I've been hearing that kind of stuff for a long time," Murphy says.

As if on cue, three middle school boys from ADL walked into the gym at Fleming School just as Murphy was packing up to leave. All three had heard his presentation that morning and had searched him out after school.

"I loved your presentation today. I thought it was really inspirational," said Alex Aubin, 14. "It really touched me, because I used to have a bully back when I was little."

"Teachers always tell you to stop it, but I've never known how," added Jonah Rice, also 14. "Now I know what to do."

Their classmate, David Amouretti, 13, said that after Murphy's assembly, he noticed an immediate change in behavior from one kid who often picks on him. Amouretti said the boy was "really quiet for a few hours" afterward.

"I think he realized that what he'd done hurt a lot of people," he said, "including me."

Amouretti's mother, Sathya, who also teaches at ADL, accompanied the boys to the gym. She called Murphy's presentation "incredible" and said she sees an immediate need for his message — not just for students but also for some of the current U.S. presidential candidates.

"I was thinking, you should go to political rallies," she told Murphy. "This is not about Democrats or Republicans. It's about, what do you want to be as a human being?"

Underdog's Best Friend

- Courtesy Of Tom Murphy

- Left to right: Jason Spector, Rick Yarosh and Tom Murphy

It's not surprising that Murphy wound up in education, as both his parents worked as teachers. His father was in alternative education, he says, and his mother taught students with special needs.

Until age 12, Murphy grew up in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia. "Not the Chestnut Hill of today," he emphasizes about a neighborhood that's since been gentrified. "We moved out of there because it wasn't a very nice place."

Beginning when Murphy was 7, his parents essentially ran a self-funded mission out of their house, taking in homeless people off the streets.

"My parents gave their only son's bedroom away to someone who didn't have a home," he recalls. "I slept in the bathtub for a year. That was just my life. I thought everyone had homeless people living with them."

As a child, Murphy occasionally saw those houseguests hauled away in handcuffs by the police. On weekends, he and his two sisters would visit these "brothers and sisters" in prison.

"Looking back on it now, I'm like, What were they, crazy?" he says about his parents' open-door policy. "But nothing bad ever happened to us. It was just people trying to get back on the right track."

When Murphy was 12, his father picked up a real estate catalog and spotted a house for sale in Cooperstown, N.Y. He drove Murphy and his mother up there and bought the place for $30,000. The property included a barn, in which his parents built apartments to take in more transients.

Although Murphy wasn't a good student in high school, that changed when he arrived at SUNY Brockport. There, he met his now-wife, Wendi, and Spector, who was a year ahead of him. When Murphy joined the wrestling team, the two became fast friends and, as neither has a brother, saw each other as "psychological twins."

"Tom has always been known for helping the underdog," Spector says. Once, in an off-season tournament, he recalls, Murphy wrestled a kid with special needs who'd never won a match before. Murphy let the kid score points on him, just to give him a taste of success. Although some of Murphy's teammates razzed him about it later, Spector says, "I think we were all secretly jealous and admired his nature."

Murphy and Spector pushed each other hard, and both eventually became all-American wrestlers; one year, Murphy placed second in the nation in his weight class. In 1998, he graduated summa cum laude with a degree in human psychology.

A summer job led him to St. Albans, where Murphy landed a position as a rail traffic control specialist with the New England Central Railroad in March 1999. There he met Charlie Moore, then a regional vice president with RailAmerica, the parent company that owned the New England Central.

At the time, Moore oversaw nine short-line railroads from Nova Scotia to Mobile, Ala. As Moore explains, all were in desperate need of professional train dispatching but couldn't afford it individually. One day, Murphy approached Moore with the idea of consolidating all those rail dispatchers under one roof and managing it remotely from St. Albans.

"It was Tom's baby. He thought of the idea," recalls Moore, who now serves on the Vermont Rail Council, a governor's advisory committee. "He was the brains of that operation."

Although he describes himself as a "young, stupid kid who didn't know anything," Murphy says, "we saved the company about $9 million a year doing it that way."

In January 2004, RailAmerica launched the American Rail Dispatching Center in St. Albans, with Moore as its president and Murphy its manager. Over the next decade, they consolidated train-dispatching services for more than 80 short-line and regional railroads around the country. When Murphy finally left the company in 2014, ARDC employed more than 40 rail traffic controllers in St. Albans.

Though Moore doesn't work with Murphy anymore, he's followed his many pursuits ever since, including "Sweethearts & Heroes."

"I have a special place in my heart for Tom," Moore adds. "He has so much passion and love for his work, it's amazing."

From Trains to Training

- Courtesy of Tom Murphy

- Tom Murphy competing in a mixed martial arts bout in Canada

When Murphy moved to St. Albans in 1999, he was still in fighting shape and wasn't ready to give it up. So he started training in Brazilian jujitsu in Burlington under Julio "Foca" Fernandez, a sixth-degree black belt who helped the sport gain popularity in the United States.

Several years later, Spike TV launched "The Ultimate Fighter," which brought the previously underground — and in many places illicit — sport of mixed martial arts to a much wider audience. A combination of boxing, wrestling and martial arts, it involves gloved and barefoot competitors who punch, kick and tackle each other in an eight-sided metal cage called the Octagon.

After the first season premiered in 2005, one of Murphy's sisters applied to the show on his behalf. He was accepted, landed a spot on Season 2, and spent 40 days in Las Vegas training and competing with some of the world's best fighters.

Jordan Breen, a Toronto-based sports journalist and administrative editor at Sherdog, a website covering mixed martial arts, remembers Murphy's career as brief but impressive.

"Individually, he was a natural athlete, a solid wrestler and a fairly crafty fighter," Breen says. "The only fighter who ever defeated him was Rashad Evans, the future [Ultimate Fighting Championship] light-heavyweight champion." And that was in the judges' decision, after Murphy fought with a badly injured knee.

According to Breen, Murphy's career was plagued by injuries — not just his own but also those of his competitors. Three backed out of high-profile bouts with him, including one in Ireland, which meant that after months of intense training and travel, Murphy didn't make any money from the matches. One opponent, Gary Goodridge, withdrew from their fight in Montréal 30 seconds before it was scheduled to start.

Although he was devastated at the time, Murphy now says he doesn't feel that way anymore. In retrospect, "For me, it was never a job. I just love to train," he explains. His last competitive fight was in 2013.

Ultimately, "I don't think Murphy saw MMA as a long-term viable career for himself," Breen concludes, "especially when he could do other things."

- Courtesy of Tom Murphy

- Tom Murphy competing in a mixed martial arts bout in Canada

Murphy discovered his latest calling, motivational speaking, almost by accident. About seven years ago, he got a call from Spector, who needed an anti-bullying presenter at Oliver W. Winch Middle School in South Glens Falls because the scheduled speaker couldn't make it. Spector asked Murphy if he would fill in.

Murphy started with some video of his UFC fights — and the kids loved it.

"After that, I won them. It didn't matter what else I said," Murphy recalls. "You put me in front of middle schoolers, I'll entertain."

But Murphy also discovered that he has much to teach kids. He and Spector have since honed "Sweethearts & Heroes" based on bullying research and their own experience of what works with kids in school settings. Murphy soon became a regular visitor to Spector's and other schools in the North Country.

In September 2014, Murphy gave his presentation to more than 300 teachers in Greenwich, N.Y., who saw it before their students did. Afterward, one teacher came up to Murphy, grabbed his hand and wouldn't let go.

"'Twenty years I've been watching presentations like this,'" Murphy recalls the man saying. "'This year is going to be different.'"

"As I drove home, that just haunted me," Murphy says. Two days later, he quit his well-paying job with the railroad so he could devote himself full time to "Sweethearts & Heroes."

When he isn't on the road or with his family, Murphy works at Twiggs: An American Gastropub, which he owns in downtown St. Albans. He bought the restaurant six years ago when it was Chow! Bella, and changed the name two years ago. Modeling his parents, he's adopted a homeless Vietnam vet who, depending on the season, sweeps or shovels the sidewalk. Murphy also previously owned a local fitness facility but says he sold it several years ago.

Ironically, students in Murphy's own town still haven't heard his presentation. Last year, he approached administrators at Bellows Free Academy St. Albans about presenting "Sweethearts & Heroes" to their students. The school declined his offer.

"Although we gave the matter careful consideration," explains Chris Mosca, principal of BFA-St. Albans, in a recent email, "we believe that events and activities that are more student-led have a greater impact on enhancing school climate and culture."

- Matthew Thorsen

- Tom Murphy speaking to elementary school students in Essex Junction

Murphy can't say for sure why some schools aren't interested in his message. It's not the cost, he says. He often convinces his corporate clients to foot the bill for local schools that can't afford to pay upwards of $3,000 for a day of trainings and presentations. Murphy bases his fees on a number of factors, including the school's size, the number of students and presentations, and the district's financial wherewithal. Ultimately, if a school can't afford him, he says, "I find a way to make it happen."

Does he face resistance because of the bloody nature of the sport in which he once competed?

"Never," the former fighter insists. "I've seen it many times before. Part of the problem is, some people just don't want to admit that they have a problem with bullying."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.