When I started dating Tim Ashe nearly a decade ago, I never dreamed we’d be in a disclosure statement together. I’m talking about the by-now-familiar disclaimer that often appears in Seven Days, variations of which have cropped up in columns and news stories since he first ran for Burlington City Council in 2004: “Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly.”

“It’s complicated” doesn’t begin to describe the potentially problematic relationship between a politician and a journalist.

“The edict has always been that you can’t have a reporter covering a lover,” St. Michael’s College journalism prof David Mindich suggested in an email after Tim, a state senator, entered the Burlington mayor’s race last fall. “As Abe Rosenthal famously said after firing a reporter who was dating a politician on her beat: ‘I don’t care if you fuck elephants as long as you’re not covering the circus.’”

My relationship with Tim is considerably less acrobatic, but it is indeed a balancing act. We approach current events from opposite directions — he’s legislating, I’m analyzing — but our worlds intersect in late-night discussions about such things as tax-increment financing and health care reform. Then we turn on “The Colbert Report.”

But there are some things we simply can’t tell each other. When Seven Days is pursuing a hot story, Tim finds out when he reads it in that week’s paper. If he has a great tip for a news reporter, he can’t give it to me. The irony: Tim probably gets less ink in this paper than he would if I didn’t work here at all.

Still, the arrangement worked just fine until he decided to run for mayor, and went from being one of 30 senators who occasionally popped up in Fair Game to a candidate in one of the most-watched races in Vermont.

I responded to the news by taking myself out of it. All of a sudden, Seven Days reporters were huddling without me. Nor was I welcome at home, where the Tim Ashe for Mayor campaign was strategizing several nights a week. When Tim and Miro Weinberger tied in the first Democratic caucus, I had to ask myself: What if Tim wins?

“Take a long sail for a long time” was one of the suggestions I got from Mark Zusman, the editor and co-owner of Willamette Week in Portland, Ore. Three months later, Zusman announced that his media company had its own conflict: Judge Ellen Rosenblum, who is married to Zusman’s partner, Richard Meeker, was running for attorney general. Zusman made the tough decision that Willamette Week would not be covering the race or making an endorsement.

Such confessions are necessary in the media business: Readers are entitled to know of any potential conflicts that might alter or slant coverage billed as “objective.”

But plenty of other Vermont couples who are similarly positioned to imperil the public trust aren’t ethically obligated to reveal themselves. Different last names and same-sex relationships make it that much harder to figure out who is with whom in a state where six degrees of separation is more likely to be one or two.

Our editorial team decided to compile a list of dynamic duos whose respective jobs could create conflicts of interest with public policy ramifications. It was easy to think of “power couples” who shared a business or endeavor — Burton Snowboards founders Jake and Donna Carpenter, publishers Margo and Ian Baldwin, Democrat fundraisers Bill and Jane Stetson, to name a few. But they didn’t fit the bill.

Nor did partnerships that qualified as high profile but not potentially problematic: WCAX anchor Darren Perron and Vermont CARES executive director Peter Jacobsen; public-access-television pioneer Lauren-Glenn Davitian and radio-talk-show host Mark Johnson; Vermont Supreme Court Justice Beth Robinson and Kym Boyman, the physician-CEO of Vermont Gynecology.

With a little help from various sources, we came up with a list of seven couples who met our criteria. Four of them agreed to be interviewed — they’re the ones with the photographs in this article. The other people we contacted outright refused, were overruled by a spouse or never called back. So we kept brainstorming. In the end, we decided to include five publicity-shy couples, too, one of which contains Mr. Transparency, Secretary of State Jim Condos. After all, their relationships are public knowledge; many of their high-profile jobs directly affect Vermonters. And Sunshine Week should really never end, should it?

One final disclosure: None of the couples mentioned in this article is pictured on the cover of this week’s Seven Days.

PAULA ROUTLY

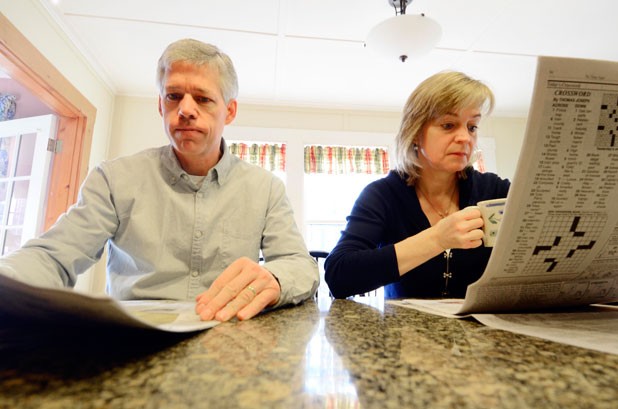

Jennifer and John Hollar

He’s the newly elected mayor of Montpelier. She’s the deputy commissioner of the Department of Economic, Housing and Community Development, which annually awards more than $10 million in grants to Vermont cities and towns for housing, land-use planning and economic development. The couple met through mutual friends on Capitol Hill, where John worked for then-Rep. Mike Synar from John’s native Oklahoma, and Jen worked for an offshoot of the National League of Cities.

Before landing their current jobs, the Hollars spent more than two decades together shaping public policy as statehouse lobbyists with the firm of Downs Rachlin Martin. Over the years, their list of clients has read like a veritable who’s who of corporate heavyweights doing business in the Green Mountain State: IBM, Verizon, FairPoint Communications, Central Vermont Public Service, Green Mountain Power, Bank of America, TransCanada, American Insurance Association, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, MVP Health Plan and Entergy Nuclear, to name just a few. The list includes some warm-and-fuzzy names, too, such as United Children’s Services, the American Cancer Society and the YMCA.

Despite the potential for conflict of interest, the Hollars seem at ease navigating the tricky waters of their current occupations. As Jen points out, John’s code of ethics as a lawyer “makes those lines that much brighter.”

As for Jen’s work with the Shumlin administration, if an instance arises where the city of Montpelier is applying for a grant administered by her agency, she will recuse herself from the process, she says.

That said, John still plans to rely on Jen’s informal counsel when he’s wrestling with one of Montpelier’s thornier municipal messes.

“It may sound a little cliché, but Jen is my closest advisor,” John says. “So when I have a very difficult problem, I’ll always talk to her about it.”

Not to suggest that sticky situations haven’t already come up. For example, since Jen was appointed deputy commish in January 2011, John’s firm has been approached by a potential client to lobby in the legislature on its behalf. Although the client, whom John wouldn’t name, doesn’t necessarily deal with Jen’s arm of state government, he says that “In that world, where we would have been dealing with the same issues but different loyalties, it just seemed too close. So we declined to take that client.”

Have you set formal ground rules for what you will or won’t discuss when you’re both off the clock?

“Obviously, [after] a quarter-century together, we know each other and have our own set of rules and an understanding,” says John. “But we don’t need to spell out a lot.”

How about when your kids were younger and you were both lobbyists?

“By eight o’clock, we were done,” John recalls. “It was partly out of just wanting to be good parents, because we could end up talking politics all night and ignore the kids.” Adds Jen, “They’re not always as interested in it as we are.”

Has anyone ever talked to one of you about the other and not realized you were a couple?

“No,” says Jen. “There aren’t too many Hollars around.”

KEN PICARD

Elizabeth and Eric Miller

Elizabeth and Eric Miller have been moving in Burlington’s legal and political circles for years. But the pair drew public scrutiny for the first time last fall when Sen. Vince Illuzzi (R-Essex/Orleans) took issue with their roles in the acquisition of Central Vermont Public Service by Gaz Métro, the parent company of Green Mountain Power. As commissioner of the Department of Public Service, Elizabeth Miller would play a key role in crafting the state’s response to the merger, Illuzzi argued, while her husband’s firm — Sheehey Furlong & Behm — represented Gaz Métro.

In response to Illuzzi’s arguments, the state hired Michael Dworkin, a former chairman of the Public Service Board, to file independent testimony on the most controversial component of the deal: the governance of the state’s electric transmission utility, Vermont Electric Power Company (VELCO), which is owned by the power companies. Responding to the perception that her department was too close to the utility companies, Elizabeth Miller said in January, “You will find significant disagreements between the department and the utilities,” according to VTDigger.org.

PAUL HEINTZ

Jim Condos and Annie Noonan

Jim Condos and Annie Noonan were already big deals in Montpelier political circles before the 2010 election made them both really big deals. Condos was elected secretary of state that November after years as a state senator representing Chittenden County. Not long after that, Noonan, the longtime director of the Vermont State Employees Association, was named commissioner of labor by newly elected Gov. Peter Shumlin. The coupling created a domestic nexus between two independently elected branches of state government. Noonan is a key member of Shumlin’s cabinet, and Condos oversees election laws — the ones that will apply to Noonan’s boss in this year’s reelection campaign.

That might actually be less thorny than Noonan’s past marriage to Timothy Noonan, who directed the state’s Labor Relations Board while Annie was head of the VSEA — a frequent party to complaints before her husband’s investigative board. Not easy relationships to navigate, but then, labors of love rarely are.

ANDY BROMAGE

Anthony Iarrapino and Joslyn Wilschek

Who says that the law is a jealous mistress? Not Anthony Iarrapino and Joslyn Wilschek, Montpelier residents and up-and-coming lawyers in two of Vermont’s most hotly contested fields: energy and the environment. He’s a staff attorney for the Conservation Law Foundation with a specialty in water and forest protection. She’s an attorney and shareholder with Primmer Piper Eggleston & Cramer, where she focuses in part on public-utility law and shepherds public and private clients through the state’s process for obtaining utility and energy project permits.

On at least one occasion, Iarrapino’s and Wilschek’s respective employers have found themselves on different sides of an issue. CLF opposed VELCO’s proposed Northwest Reliability Project, a transmission upgrade that stretched from West Rutland to New Haven. Wilschek’s firm represented VELCO, and Wilschek worked briefly on a planning docket for the Public Service Board. Iarrapino didn’t work directly on the case; in fact, most PSB proceedings are handled by another lawyer at CLF.

Occasionally, professional matters have paved the way for cooperation between the spouses: When neighbors concerned about Act 250 proposals called CLF for help, Iarrapino — with full disclosure — would sometimes refer the calls to Wilschek and a handful of other private attorneys more suited to the case.

So far, though, Iarrapino says the couple hasn’t encountered a conflict of interest in the true, legal definition of the term — which, of course, is the one that matters to a pair of attorneys. “I’m glad that we haven’t had to confront that issue,” he says. “Whether or not it’s a legal conflict of interest, I think it would make for a difficult situation at home. We just haven’t had to deal with that.”

KATHRYN FLAGG

Tasha Wallis and Kevin Goddard

How’s this for pillow talk? Health care reform! That complex topic may be near and dear to one powerful Vermont couple: Morristown residents Tasha Wallis and Kevin Goddard. Former journalist Goddard is No. 2 in command at Blue Cross Blue Shield Vermont, the state’s largest health insurer, where he is ensconced as the vice president of external affairs. Wallis, meanwhile, has headed the Vermont Retail Association (VRA) since 2007. Previously, she served a long tour of duty in state government, first as former governor Howard Dean’s policy advisor and commissioner of labor and industry, then as commissioner of buildings and general services under governor Jim Douglas.

Both have spent plenty of time at the Statehouse over the years — though Wallis and Goddard didn’t meet until an encounter at a governor’s ball. When they’re not wading into state policy and regulation, the couple have a side gig: a joint photography business.

Both the small business community — which Wallis represents — and BCBSVT are scrambling to make sense of what health care reform will mean for Vermont. The insurance company has angled for a seat in the debate, positioning itself as a nonprofit with experience and wisdom to offer as the legislature hashes out health care exchange regulations. BCBSVT already has a vote of support from one corner. “Other health plans come and go, but for decades Blue Cross Blue Shield of Vermont has remained the gold standard for secure, high-quality health plans,” the VRA website reads. “Thanks to VRA’s special relationship with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Vermont, we offer members competitive premium rates, access to all desirable benefits, and superior customer service.”

KATHRYN FLAGG

Dennise Casey and Neale Lunderville

Love blossoms in the most unlikely places — sometimes even in the governor’s office on the fifth floor of the Pavilion Building. For years, Dennise Casey and Neale Lunderville dated while working side by side for former governor Jim Douglas. She managed Douglas’ 2008 reelection campaign and served as the gov’s communications director and deputy chief of staff. Lunderville ran Douglas’ 2002 and 2004 campaigns and held three cabinet positions, including the all-powerful Secretary of Administration post.

The two are still a couple, but are no longer colleagues. Casey left Douglas’ office to direct the Republican Governors Association’s New England ad buys during the 2010 election cycle; these days, she runs her own political consulting shop in South Burlington. Lunderville took a job with Green Mountain Power, though he briefly reentered state government last fall, when Gov. Peter Shumlin tasked him with directing Tropical Storm Irene recovery efforts.

PAUL HEINTZ

Clare Buckley and Michael Obuchowski

For the first 15 years of their relationship, Clare Buckley had to disclose any gifts she gave her boyfriend, Michael “Obie” Obuchowski, in excess of $5 — and then, when the law changed, $15.

“We just decided early on we weren’t going to disclose our lives to the secretary of state’s office, so I would just not give him anything worth more than that,” she says. “You become very creative when you have that limit.”

But because Buckley was the lobbyist — she’s a partner at KSE Partners — and Obuchowski was the lawmaker — he represented Bellows Falls in the legislature for 38 years, six of them as Speaker of the House — he could give her gifts of any value without disclosure.

“That sort of put me on the short end of the stick,” he recalls.

The pair finally tied the knot in July 2010 and are now the busy parents of 16-month-old twins, Jack and Norah. “They’re the real power couple,” Obie says.

Obuchowski’s job has also changed. In December 2010, he was appointed commissioner of the Department of Buildings and General Services — a position that became a lot more complicated when Tropical Storm Irene rendered much of the 50-buildings state office complex in Waterbury unusable.

As Obuchowski led the Shumlin administration’s deliberations over whether to relocate 1500 displaced state workers elsewhere in the state for good, the town of Waterbury hired Buckley’s firm to lobby lawmakers to keep the workers where they were. But, according to Buckley, she has had nothing to do with that particular issue.

“The firm does represent Waterbury, and obviously Waterbury is a very interested party to what’s happening, but I’m not working on that at all,” she says. “The people of Waterbury wouldn’t even know who I am.”

Buckley and Obuchowski say they avoid conflicts of interest simply by refraining from bringing work home.

“He never talks to me about his work. Ever,” Buckley says. “I know what he’s doing from the newspaper or TV.”

According to her husband, “I work hard and put so many hours into the work side of my life that, when I’m separate from that, I like to escape it.”

After 15 years of living an hour and a half away from each other, what’s it like finally to live under the same roof in Montpelier?

“For me, obviously, with the twins, I don’t know how I would do it if I was by myself,” Buckley says. “You just need two people on the weekend, even if you want to go out to the grocery store. It’s definitely very nice for us to be in the same place.”

Is it difficult for a lobbyist and commissioner to coexist without conflicts?

“Vermont’s a small state,” Obuchowski says. “You can’t help who you fall in love with, and you just sort of find yourself in these situations, and you have to deal with it as respectfully as you can.”

Are Jack and Norah sporting facial hair like their famously mustachioed father?

“That’s what everybody asks me,” Buckley says. “Everybody says that on our Christmas card we should give them mustaches. Not quite yet. At 16 months, you don’t quite get facial hair.”

PAUL HEINTZ

Margaret Cheney and Peter Welch

On January 2, 2009, Vermont’s lone congressman, Democratic Rep. Peter Welch, married state Rep. Margaret Cheney at her home in Norwich. It was a small and intimate affair held in Margaret’s living room, officiated by a justice of the peace and Peter’s sister, Maureen, an Ursuline nun. No congressional bigwigs attended, nor were there TV cameras or a gubernatorial security detail. Headline their story, “Two Houses, One Love.”

To be accurate, Welch and Cheney actually maintain four residences: the one they share in Norwich, Welch’s previous house in Hartland, his apartment in downtown Burlington and his apartment in Washington, DC, where he sleeps weeknights when Congress is in session. This is a second marriage for both. Cheney divorced her first husband, with whom she had three children. Welch’s first wife, Joan Smith, died of cancer in 2004. She had four children and adopted a fifth with Welch.

Welch and Cheney both insist they didn’t deliberately keep their relationship on the down-low — from their constituents or the press.

“It was a combination of things that had much more to do with personal considerations than public considerations,” Welch explains. “Plus, somebody who wants to marry me needs to kick the tires pretty good first.”

“We were certainly public about seeing each other,” Cheney adds. “I guess no one was paying attention.”

Not that there was much reason for either to go public about it. As Welch points out, their work has very little official overlap; her arena is primarily state policy, his federal.

“The issues we have to deal with are completely separate,” Welch explains. “So there’s not a conflict between us in how she does her job to how I do my job. But there’s a mutual interest, and I have an intense interest in what’s she’s doing.”

Indeed. Prior to his election to Congress in 2006, Welch spent 13 years in the Vermont Legislature, where Cheney serves with many of his former colleagues.

Likewise, DC is hardly unknown territory to Cheney. From 1978 to 1989, she worked as editor of the Washingtonian Magazine. And, when she was a child, Cheney’s father was in the foreign service and worked as a state-department official.

In fact, Welch says his wife still has a much better working knowledge of the city than he does — and knows a thing or two about influencing policymakers. On a recent visit, for example, she cooked dinner for five Democratic and five Republican colleagues of Peter’s.

“It improved my respectability quotient considerably,” Welch quips. “They saw that there must be something redeeming about me.”

Margaret, do you ever advise Peter on how to deal with the press?

“He’s so able by himself,” she says. “Hearing him as a former journalist, I’m always amazed that he just cuts to the essence and makes his message succinct. If he weren’t like that, I’d probably be frustrated and advising him all the time.”

Did you ever consider taking his name?

“No, I’ve always been Margaret Cheney. Born that way and stayed that way.”

Has anyone ever complained to you about Peter, not knowing that you’re a couple?

“No, nothing like that,” she says. “Of course, complaints about Congress are so common, so they’d probably happen regardless.”

KEN PICARD

Sandy and John Dooley

He’s a Vermont Supreme Court justice. She’s a South Burlington city councilor. Together, Sandy and John Dooley have probably navigated more potential conflicts of interest than virtually any other couple in Vermont — and have often done so in the public eye.

Case in point: In November 2005, John became the first supreme court justice in anyone’s memory to appear as a litigant in his own courtroom. The case involved the Dooleys’ decades-long fight to stop a development that would have obstructed their view of the Green Mountains. Because of the Dooleys’ involvement, all five justices bowed out and allowed the case to be heard by a panel of replacement judges.

That wasn’t even the first public conflict of interest with which the couple wrestled. In 1999, the supreme court was scheduled to hear Baker v. Vermont, the landmark case that established the right of same-sex couples in Vermont to join in civil unions.

At the time, Sandy was serving on the Vermont Commission on Women, which had nominated the plaintiffs in the Baker case for a regional award — and Sandy had voted in favor of the nomination. As Sandy recalls, she had flown to Vancouver, B.C., to join John, who was there attending a convention. While they were away, somebody from an anti-same-sex-marriage group learned of Sandy’s vote and demanded John’s recusal from the case. The couple returned days later to a deluge of phone messages from the press.

Interestingly, Sandy remembers that a parallel controversy had just arisen involving a Franklin County judge whose wife chaired a local right-to-life committee. The judge, who was scheduled to hear an abortion-related case, faced similar criticisms and calls for his recusal. Fortunately, Sandy says, Vermont’s Judicial Ethics Committee determined that neither spouse’s political activities were sufficient to force their respective judicial spouses to step aside.

“It articulated the independence of spouses to have different roles,” Sandy says. “I would have hated to have felt I had to abstain from the nomination. But I also would have hated for John to have to recuse himself from one of the most important decisions the court ever had to make.”

John, are perceived conflicts of interest harder for you as a Vermont Supreme Court justice because judges are expected to be paragons of impartiality?

“It’s actually easier for judges, because we have a very clear system of what we do and what the ethical limits are,” John says. “You just get used to the fact that, if you don’t sit on a case, you don’t sit on a case. That’s just the nature of a small state. So the land-use policy of the city of South Burlington is her responsibility; it’s not mine.”

Any informal ground rules about not talking shop at home?

“Oh, sure,” Sandy says. “If we have friends over for dinner, I can’t be the only nonlawyer.”

KEN PICARD

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that Jim Condos was on the Senate Government Operations committee while he dated Annie Noonan. This is incorrect.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.