- Paul Heintz

- Calvin Coolidge's birthplace and church in Plymouth Notch

Six days a week, John Donald walks a quarter mile from his Plymouth Notch farmhouse to the hilltop hamlet's tiny post office, where he works part-time as its sole employee. The 73-year-old postmaster's commute bisects the Calvin Coolidge Homestead, a compact collection of buildings that have stood largely unchanged since 1923, when America's 30th president swore the oath of office by lamplight in his childhood home.

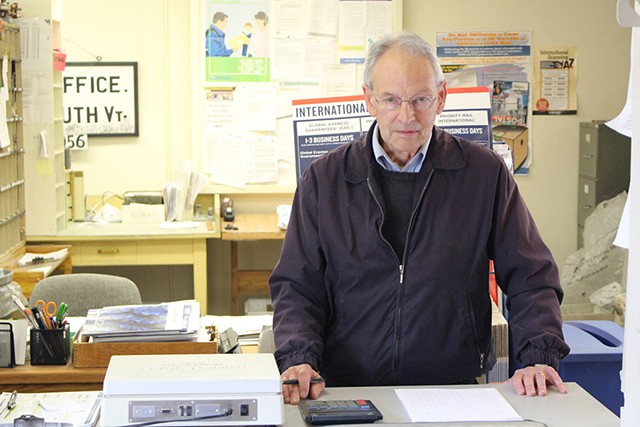

"Being that I've been here just about all my life, I know just about everybody in town," the wiry, bespectacled man said last Friday afternoon from behind the post office counter in the tiny, southern Vermont village, just south of Killington.

Donald couldn't say the same about the conservative donors who, in recent years, have taken over the sleepy historical society once known as the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation. Back when Donald served on its board and his wife, Kathleen, was its executive director, the foundation was a "backroom operation with a very limited budget," focused on preserving the homestead and Coolidge's memory.

These days, the rechristened Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation has deeper pockets and greater ambitions: to become a national institution befitting a former president and to spread his gospel of fiscal discipline.

Now run by two alumni of the George W. Bush Foundation, the Vermont nonprofit has attracted major conservative donors to its board — including one of President Donald Trump's top financial backers, the New York City heiress Rebekah Mercer. Since 2008, she and her father, Long Island hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer, have donated more than $77 million to conservative causes — and bankrolled chief White House strategist Steve Bannon.

Like others in town, Donald bears no ill will toward the reconstituted Coolidge Foundation, whose offices remain just across the road, in the basement of the state-owned Coolidge Museum and Education Center. But the postmaster wonders why the nonprofit has become so "focused on money."

"For folks that were [involved] back in the original time of it, it's almost like night and day," Donald said, recalling bygone board meetings attended by the president's late son, John Coolidge.

- Paul Heintz

- John Donald at the Plymouth Notch Post Office

The foundation's transformation has drawn sharper condemnation from others, including Montpelier historian Howard Coffin, who served on the Coolidge board for two decades.

"It's clearly a partisan, rightwing organization," said Coffin, a former press secretary to the late Republican-turned-independent senator Jim Jeffords. "I think Coolidge would be turning in his grave with what's happening at that foundation."

Former Republican governor Jim Douglas, who has served on the board since 2011, acknowledges that the foundation has "matured quite a lot" in recent years, but he disputes the notion that it has become politicized.

"There's no question it's a different organization. It's a national board. We're raising more resources to support our efforts, so there are growing pains," said Douglas, one of just four Vermonters remaining on a board of 20. "That may make some people uncomfortable, but I don't see any ideological imprint on anything we do as an organization."

Indeed, many of the foundation's programs appear nonpartisan. It continues to partner with the state to provide seasonal educational events in Plymouth Notch. More recently, it has established a high school debate competition that culminates in a Coolidge Cup finale each summer at the president's birthplace. And last year it created a Coolidge Scholarship, which provides four years' college tuition to two to three students.

Its Coolidge Prize for Journalism, however, seems to have a more ideological bent. Awarded annually to those who articulate the tax-cutting ideals of the late president, its $20,000 purse has gone to a regulatory lawyer, a libertarian economist and a Wall Street Journal columnist.

"We're trying to promote the Coolidge values of civil discourse and a robust democracy," said foundation executive director Matthew Denhart.

Detractors and defenders alike credit the same person with reimagining the foundation: Amity Shlaes, a conservative scholar who previously served as a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and as a member of the Wall Street Journal editorial board.

Shlaes was elected to the Coolidge board in 2011 while researching a biography that recast the oft-mocked "Silent Cal" as a tax-cutting hero of the right. Three years later, Shlaes was elevated to board chair and hired as chief executive officer — a newly created position — after the free-market-oriented Thomas W. Smith Foundation committed $1 million to finance her salary for four years.

At the same time, the board also hired Denhart, then a 26-year-old researcher who worked with Shlaes at the Bush Foundation, to serve as executive director.

According to Coffin, no Coolidge employee earned more than $50,000 a year when he served on the board. Cyndy Bittinger, the foundation's executive director from 1990 to 2008, said she earned "a basic salary" in that position.

"It was very modest," the Hanover, N.H., retiree said.

Filings with the Internal Revenue Service show that employee compensation at the Coolidge Foundation jumped from roughly $136,000 to $423,000 the year Shlaes and Denhart were hired. In 2015, the most recent year for which IRS records were available, Shlaes earned nearly $202,000 in salary and benefits, while Denhart made $131,000. That accounted for about one-third of the foundation's $906,000 budget.

Though she was promised an even higher salary when she was hired, Shlaes said she asked the board to redistribute some of it to other employees.

"The bottom line is that while we received a commitment for $1 million for my employment, I discovered I could not take the $250k a year planned without touching our endowments for other outlays," she said in an email after declining multiple interview requests. "My goal was to help the foundation, not the other way."

Unlike Denhart and Coolidge's four other full- and part-time staffers, Shlaes does not work out of the Plymouth Notch office. She lives in New York City, where she serves as a presidential scholar at the King's College, a Christian liberal arts institution once run by the conservative firebrand Dinesh D'Souza.

Shlaes also finds time to advance her political agenda in the press, often invoking Coolidge's legacy and the foundation that bears his name.

In a column last December for Forbes, she extolled "the greatness" of Trump's initial pick for labor secretary, Andrew Puzder — the fast-food tycoon who later withdrew from consideration following allegations that he abused his first wife and employed an undocumented immigrant. In recent years, Shlaes and Denhart have co-authored pieces for the National Review praising then-senator Jeff Sessions as a fiscal hawk and criticizing Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) for proposing a tax plan that "does not go nearly far enough in cutting marginal taxes."

In a speech sponsored by the Charles Koch Institute at February's Conservative Political Action Conference in Maryland, Shlaes drew applause after noting, "Yesterday, right here at CPAC, President Trump promised that the forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer!"

According to Shlaes, her work for the Coolidge Foundation is "national" in scope and requires frequent travel to spread the word and raise money.

"We are like a startup," she said.

Shlaes has certainly found success courting generous donors. In 2011, the year she joined the board, the Coolidge Foundation raised just $160,000, IRS records show. In 2014, when she took over the organization, it took in $409,000 in donations. The next year, that figure jumped to $774,000.

The foundation does not identify its donors, but according to Douglas, all board members are expected to contribute. How much the Mercers give is unclear. Shlaes would not say, and a spokesman for Rebekah Mercer declined to comment.

- Paul Heintz

- Wilder Barn at the Calving Coolidge Homestead

According to the Washington Post, the Mercer Family Foundation has contributed more than $36 million since 2008 to conservative think tanks and other nonprofits, including the climate change-denying Heartland Institute, the anti-Clinton Citizens United Foundation and the court-focused Federalist Society. The family invested at least $10 million in the Breitbart News Network and owns Cambridge Analytica, the data science firm that advised the Trump campaign.

The family has also donated $41 million to Republican office-seekers since 2008, according to the Post. They were among the first major donors to shift their support last summer from Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) to Trump following the GOP presidential primary — and helped install Bannon and Kellyanne Conway as the Trump campaign's new leaders. When Bannon considered resigning his White House post earlier this month, it was Rebekah Mercer who convinced him to stay, according to a Politico report.

In a recent profile of the Mercer family, the New Yorker's Jane Mayer quoted Shlaes praising the clan as "enchanting firecrackers" and Rebekah as "into action."

"The Mercers have strong values, they're kind of funny, and they're really bright," she told the magazine. "Their brains are almost too strong."

When Woodstock resident Mimi Baird served on the Coolidge board, from 1994 to 2012, she said, "We were bipartisan. We made a big point of having people from all stripes be on our board. And we didn't talk politics. We talked Coolidge."

A review of the board's current makeup suggests that's no longer the case. Its members include CaptiveAire Systems founder Robert Luddy, a North Carolina charter school advocate who donated more than half a million dollars to conservative candidates during the 2016 election; Boston private equity billionaire John Childs, who has spent close to $10 million on conservative causes in the past six years; and C. Boyden Gray, an heir to the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco fortune who served as White House counsel in the first Bush administration and ambassador to the European Union in the second.

Like Douglas, Shlaes denied that the Coolidge Foundation has become "a partisan instrument."

"Some of our donors give money to political causes," she said. "But as donors or trustees, they apply no inappropriate pressure."

During Coffin's era, the board was mostly comprised of locals and state political figures. These days, the only Vermonters left are Douglas, former Rutland Herald publisher Catherine Nelson, Manchester consultant Leslie Keefe and Norwich business owner Ann Shriver Sargent.

Coffin said he is most concerned about the foundation's relationship with the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, which owns most of the buildings on the Coolidge Homestead. The foundation owns only the village's Union Christian Church, but it occupies, rent-free, 2,100 square feet of office space in the museum and education center, thanks to its financial support for the building's construction in 2009.

"I don't think that a clearly politically partisan organization should be using that state facility," said Coffin, who helped raise the money to build it in the first place.

"We're aware of the current direction, if you will, that [the foundation is] taking," said state historic preservation officer Laura Trieschmann. "We're aware of their politics."

According to Trieschmann, Shlaes and her colleagues broached the topic of inviting Republican presidential candidates to Plymouth Notch last year, but the state put the kibosh on the idea.

"It's a historic property," she said, emphasizing that the two entities have been able to reconcile their different approaches. "It's not to be used to promote current politics in any way."

Like Donald, the postmaster, Plymouth Notch resident Phyllis Martin has watched with wonder as the Coolidge Foundation has outgrown its roots.

"From what I hear, they're more into getting all the money that they can — the grants and things," she said last Friday outside her home on the outskirts of the village. "I don't know that they have done so much for the town."

Martin, whose family has lived in the notch for at least seven generations, spent three decades working for John Coolidge at the Plymouth Cheese Factory and another two decades as town clerk and treasurer. Her father, she said, knew the president.

- Paul Heintz

- Cedric Johnson, Phyllis Martin and Don Martin in Plymouth Notch

Standing next to a green John Deere tractor beside her husband, Don, and brother-in-law, Cedric Johnson, Martin recalled with nostalgia the years when Plymouth Notch was a major tourist attraction — in the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

"It'd be hard to drive down through there," she said, of the once bustling village. "It's not like it was years ago."

Nor, she noted, were the nation's politics.

"If he was around today," Martin said of Coolidge, "things might be a little different."

Comments (11)

Showing 1-11 of 11

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.