In the years before Hurricane Katrina, Chris Rose penned an entertainment column for the New Orleans Times-Picayune’s “Living” section.

While it was not exactly supermarket tabloid fodder, Rose often riffed on Britney Spears, Jessica Simpson, Sean Penn and other celebrities who behaved badly in the Crescent City.

But after the levees broke, Rose’s prose — and his life — underwent a sea change. His columns became surreal, sometimes darkly comic diary entries about life in post-Katrina New Orleans: street feuds about smelly, discarded refrigerators; waiting in line to fill a prescription; finding a dead body on a neighbor’s porch. Week after week, Rose laid bare his personal pain and foibles, including his descent into depression and addiction.

“We reporters go to other places to cover wars and disasters and pestilence and famine,” Rose wrote in September 2005. “There’s no manual to tell you how to do this when it’s your own city. And I’m telling you: It’s hard . . . It’s hard not to be very, very afraid.”

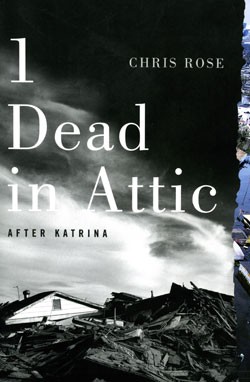

Rose’s words struck a chord with his fellow residents as they, too, struggled to rebuild their shattered lives. His columns, often described as the “voice” of post-Katrina New Orleans, earned him a Pulitzer Prize and were later compiled into a national bestseller, 1 Dead in Attic.

This week, Rose visits Johnson State College to discuss his book, part of JSC’s Common Reading Initiative for incoming freshmen. Seven Days caught up with Rose by phone last week from New Orleans.

SEVEN DAYS: How was the Times-Picayune perceived before Hurricane Katrina?

CHRIS ROSE: We’ve always been a very vital and vigorous part of the community here . . . What did not happen before the storm that happens now is that, when you get introduced as being from the Times-Picayune at a Chamber of Commerce luncheon, people stand up and clap for you. We’re treated as heroes.

Katrina brought back that very poignant, meaningful mission of journalism — like it really, really mattered every day what came down on people’s doorsteps. Suddenly, high school students to folks 90 years old were reading the paper because we were the only ones people could trust.

The storm brought down a quintessential dichotomy in the community: There were those who cut and run, and there were those who stepped up, at great sacrifice. There’s no question, no question, the Times-Picayune stepped up. And in the vacuum of political and corporate leadership, we carried the fucking day in this town.

SD: How’d your readers respond to the transition?

CR: At the beginning, we were all on the same ride together. It seemed that everyone was going up at the same time and coming down at the same time. All I was doing was documenting my own life. And that’s what’s been strange about it, is that, these labels and monikers that have been attached to me — the “voice of the city” and stuff like that — it’s a heavy mantle to wear . . . I’m not an extraordinary man, and I’m not an extraordinary writer. But I live in extraordinary times.

SD: Did the voice of other reporters at the paper change as well?

CR: There’s no question that from the day it came down, the notion of objective journalism was washed away with everything else in this town. I don’t think the paper has ever pretended to be objective since. We write with a really interesting edge and a real gripping tone, which is why I think we’re the most relevant local paper in the country.

SD: How’d it happen?

CR: Let’s put it this way: The writers and the photographers were in the city and management was relocated to Baton Rouge by virtue of our building flooding. You take management and move them 70 miles away from staff, and we win two Pulitzer prizes. You think that’s a coincidence? That’s not only a paradigm shift to follow in journalism, but in any corporate structure.

SD: Tell me about this new sense of mission.

CR: There’s no pretending to be objective. What we’re fighting to save here is our city, our culture, and by extension, our jobs, our houses, our schools. When we write this shit, we don’t just report the stuff and let it fall where it may. We’ve got way too much at stake to be dispassionate observers covering a sporting event and not caring who wins.

SD: What can small community newspapers learn from your experiences?

CR: The truth is, the list of communities that have gone through a communal and broad crisis existed long before us. Take Oklahoma City and New York City. The shit’s coming down, and it keeps on coming down, whether it’s by natural or unnatural causes. The lessons are, you can anticipate it and amp it up now and hope the community goes along with it.

SD: Is the glass half full or half empty in New Orleans?

CR: Or is the glass just broken and lying on the ground? In the early days, the community used to move in one big paradigm shift together. It was optimistic in the times at Jazz Fest and Mardi Gras, and pessimistic during the long, hot summer days when nothing’s going on . . . There are large swaths of New Orleans, particularly those areas most visitors, tourists and conventioneers are used to, that you can percolate through and never see any physical manifestation of the storm whatsoever. Unless, of course, you look too closely into somebody’s eyes.

SD: What keeps you there?

CR: My kids’ school and my paycheck . . . Often I think I’m ready to pack it up, move to a beach somewhere and live a shoes-optional lifestyle. But it’d be hard for me to move to another city or town anywhere [else] in this country because, as I’ve learned, the longer you’ve lived in New Orleans, the more unfit you become to live anywhere else, which is comic but true.

I’ve also realized that the only thing worse than being in New Orleans — when you really have a stake in all this — is not being here. My most troubled and tormented friends and associates are those who were forced to move away and can’t get back. At least the rest of us here have people around who understand.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.