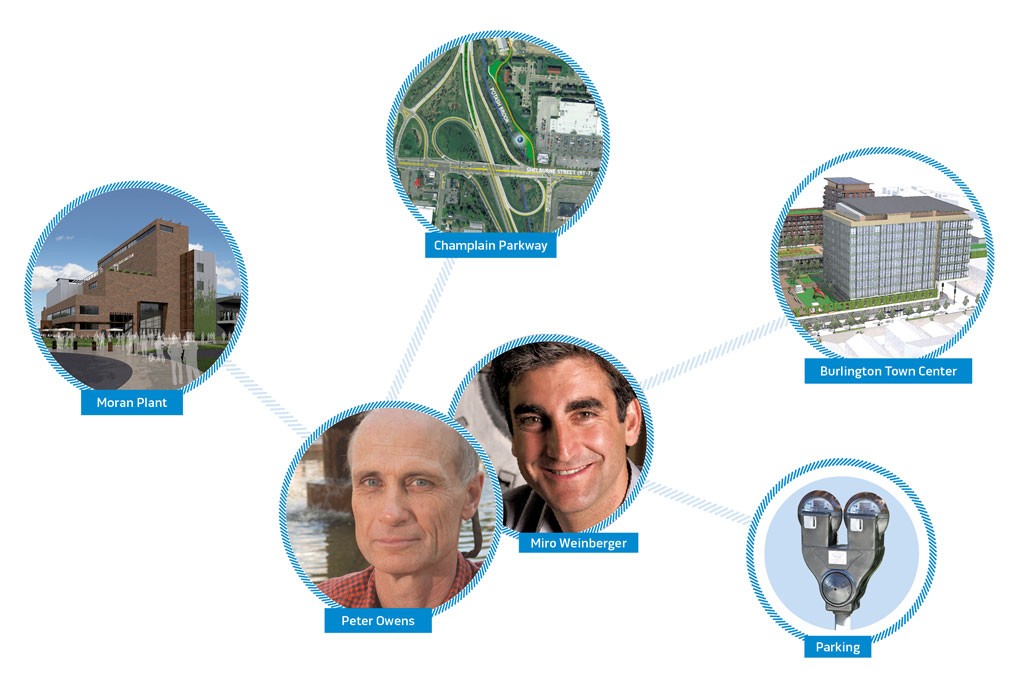

- Owens, Weinberger, Parking Photos File: Matthew Thorsen

In his campaign stump speeches around the country, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders rattles off accomplishments from his eight-year tenure as mayor of Burlington: the Waterfront Park, the community land trust and citywide neighborhood planning assemblies to encourage citizen involvement in government, to name a few.

Many of those initiatives came out of the Community & Economic Development Office Sanders created in 1983. By one vote, the underdog socialist mayor managed to convince a mostly hostile city council to establish the unique entity that would help him bypass political gridlock. Conveniently, most of the department's budget came from federal grants instead of city coffers.

"A lot of people don't understand what CEDO does," observed Beth Truzansky, who recently left after working there for 13 years, most recently as director of a diversity and equity program. But insiders consider the de facto department to be the mayor's activist arm.

Located right next to the mayor's office, CEDO helped carry out many of the hallmark initiatives of Burlington's Progressive era. It invested in underserved neighborhoods and rehabbed North Street. It helped build Burlington's acclaimed affordable housing network by setting up what is now the Champlain Housing Trust — a community land trust that manages and builds affordable housing. It led efforts to create inclusionary zoning and expand tenant rights. More recently, the office nurtured businesses such as Burton Snowboards in the once-barren South End and paved the way for downtown City Market/Onion River Co-op.

In 2013, former and current staff convened at Burlington's city hall to celebrate CEDO's 30th anniversary. Sanders, then a senator, showed up to expound on the department's successes during his time as mayor. CEDO eschewed the "give tax breaks, beg, go to other states to bring companies here" approach to economic development, he said. Instead, "We began by asking the question, economic development for who?"

John Davis, who spent a decade as CEDO's housing director, said the office's work was guided by a maxim that Sanders beat into their heads: "What's in it for the little guy?" It was also defined by "a healthy skepticism about market solutions — skepticism about private developers and private banks doing the right thing without some checks and balances," Davis said.

But now that it's under Democratic command, some city councilors worry that CEDO is in the throes of an identity crisis. Different priorities, staff departures and a proposed restructuring have prompted questions about whether it is losing its way.

City council president Jane Knodell, a Progressive, recalled a time when "it was clear the vision was: We want development but we also want equity, and we want to make sure we don't displace working-class people from the city." Now, she said, "It would be hard for me to articulate the vision behind CEDO."

CEDO's first director, Peter Clavelle, followed Sanders as mayor. When Weinberger took Burlington's top job in 2012, the office had been under Progressive control for all but two years since its creation.

The newly minted Democratic mayor picked Peter Owens, a development specialist with a PhD in environmental planning and urban design, to head up the office. Before coming to Burlington, Owens was the urban design director at a White River Junction landscape architecture and planning firm. He helped redevelop the Presidio, a former military base in San Francisco. Fresh out of Middlebury College in the 1980s, he also did some work for CEDO.

Under Owens, CEDO is leading several public and private infrastructure projects on the waterfront, including redevelopment of the Moran Plant. It's redesigning the city's parking system and promoting dense mixed-use development in the downtown by supporting projects such as the $200 million mall makeover. In the South End, CEDO is planning for the construction of the Champlain Parkway and redevelopment of the nearby rail yard. One of Owens' and Weinberger's more ambitious — and contentious — goals is an 18-point housing plan, which aims to make housing more affordable for middle-income people.

Lately, though, they've been addressing more mundane matters regarding budget and personnel.

CEDO has been wrestling with serious financial challenges precipitated by a steady decline over the years in the federal funding that accounts for most of its budget. For example, Weinberger noted in an interview that the community development block grant, an annual source of money used for a variety of projects, dropped 20 percent due to federal cuts about the time he took office.

"I can't tell you how stressful it's been these last two springs, trying to deal with this budget ... trying to scramble around to find money to pay staff," Owens said. The reporting requirements for the remaining grants have become more onerous, taking up more staff time.

Owens recalled that during his earlier stint at CEDO, the office "had incredible flexibility to do all kinds of things." In today's funding climate, he continued, "We don't have the dollars, and we don't have the flexibility."

Even so, he's adamant that CEDO is on the upswing. "I'm actually pretty psyched," Owens said. Describing it as "the end of a three-year effort to get a solid foundation," he added, "I feel like we are starting to get our mojo back."

Helping to stabilize the situation: The city council agreed to start giving CEDO an annual allocation from the general fund. Roughly $400,000 of its $4.5 million budget now comes from local tax dollars.

Staff turnover has also been a problem. During the past year, roughly a quarter of the 30-person team has left, including holdovers from the Progressive era such as Denise Girard, who left after approximately three decades, 18-year veteran Brian Pine and Nick Warner, who ran the brownfields program for 16 years. When Owens' right-hand man, Nate Wildfire, leaves in August after two and a half years, he'll be the third assistant director to depart in roughly six months. A fourth assistant director, Darlene Kehoe, moved to the clerk/treasurer's office but continues to manage finances for CEDO.

The staff departures, Owens acknowledged, have been hard. But he put a positive spin on the situation, pointing out that CEDO is continuing its tradition of being "an incubator for leaders in the community." And, he added, the departures gave him an opportunity to restructure the office in a way that will make it more effective.

His plan came up for a vote at the June 15 city council meeting as part of the mayor's fiscal year 2016 budget proposal. It was the only sticking point between the administration and the council that evening. During earlier meetings, Owens had explained his logic for the new arrangement, which eliminates the housing division and distributes its work between two other teams, renamed the "sustainability, housing and economic development division" and the "community, housing and opportunity division." He insisted that housing would actually get more attention under the new arrangement because it would no longer be in a "silo" and more people would be working on it. He argued that separating federally funded housing work from city-funded work would make it easier to meet the former's reporting requirements.

One by one, non-Democrats on the 12-member council expressed misgivings about the plan. Despite Owens' assurances to the contrary, they suggested that eliminating the position of assistant director of housing, which oversaw the housing division and was previously occupied by Pine, would weaken the city's response to one of its primary challenges.

"For me the question is, does this diffuse the issue of housing so much that it becomes kind of a demotion?" Progressive Councilor Selene Colburn asked in an interview.

"When everybody is in charge of something, no one is in charge," Knodell later noted.

The councilors ultimately agreed to the change, but the discussion that night hinted at a deeper conflict.

"I think a lot of the criticism of CEDO is really disagreement with the policies and priorities of the administration," said Davis, who started working there in 1984. "CEDO becomes a lightning rod."

Davis was hesitant to criticize the current incarnation of CEDO, noting, "There's always a risk of old-timers looking at any agency of which they were a part and then saying in a very self-serving, self-congratulatory way that those young whippersnappers are doing it all wrong."

But he did say CEDO seems to have a different set of "social priorities" than it did during his time there.

According to Knodell, CEDO is devoting less attention to community development projects that invest in neighborhoods and address poverty-related issues. Progressive Councilor Max Tracy said he thinks CEDO lacks a "comprehensive antipoverty strategy." On the subject of housing, he criticized it for catering more to a 20- to 40-year-old "techie set" than to low-income residents.

Owens and Weinberger vigorously deny the suggestion that CEDO's commitment to helping low-income residents has waned, or that CEDO has drifted from its mission, which Owens describes as "building a vibrant, healthier and more equitable city." But both men acknowledge that they do intend to spend more time addressing the housing needs of middle-income residents.

"We're not backing away from affordable housing one inch," Owens said. "But we are recognizing that there are additional things that we can do in terms of neighborhood livability, student housing and workforce housing."

People such as Tom Torti, executive director of the Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce, welcome the greater focus on young professionals. The mayor and his CEDO staff, Torti said, "are not paralyzed by fear. They are not paralyzed by process."

The mayor also defended CEDO's overall record, saying, "If you look around the city right now, there's a lot going on, and I think that is a demonstration of us continuing to find a way to move things forward, even if CEDO is going through some restructuring."

Are Progressives simply feeling protective of the historically liberal enclave? "That's probably part of it," Knodell conceded. But she doesn't think it will inevitably remain a point of contention. "I think it's a huge opportunity for the mayor to rebuild CEDO to carry out a positive vision for Burlington, and I think it can be done."

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.