- Jordan Silverman

- Allan Hunt

Allan Hunt watches from his front porch on Maple Street as rush-hour traffic inches east toward the most congested four-way stop in Burlington. Staked into Hunt’s greenbelt is a homemade sign with a message to all who pass: “Stop the Champlain Parkway!”

A man driving a silver Toyota Tundra notices the sign and yells out his window to Hunt, “What’s the Champlain Parkway?”

“It’s a highway they want to build down Pine Street,” Hunt answers.

“That would be great!” the driver says.

“Not if you live here,” Hunt replies as the silver pickup roars through the dreaded intersection at Maple and Pine.

Hunt has been planting his signs in strategically placed South End greenbelts in anticipation of yet another milestone for the long-stalled highway project. After 45 years of delays and false starts, the $25 million Southern Connector — since renamed the Champlain Parkway — is in Act 250 permit hearings. If the city clears that final hurdle — and Hunt doesn’t appeal the panel’s decision — road construction could begin as early as next year.

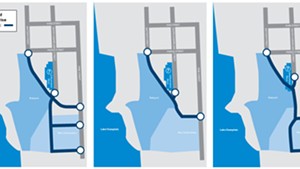

The Champlain Parkway now under consideration is nothing like the grandiose plan envisioned four decades ago. What started as a four-lane, limited-access highway that would zoom alongside Lake Champlain has been downsized to a two-lane, pedestrian-friendly urban boulevard beautified with trees and new sidewalks. The abandoned portion of the original road, which is sprouting weeds off Interstate 189, would be torn up and reconfigured into a gentler road with 30-miles-per-hour speed limits.

But the project’s goal remains the same: to divert traffic — particularly noisy truck traffic — from residential side streets such as Flynn and Home avenues onto a central thoroughfare.

Now that it might actually happen, a small but dedicated group of opponents are speaking out against a road project they view as outdated, expensive and unnecessary. Hunt, who lives at 89 Maple Street and owns a four-unit rental property next door, has given out 30 anti-parkway lawn signs. He also recently hired a lawyer, Frank Kochman of Burlington, and a traffic consultant to counter the city’s experts during the Act 250 hearings. He testified at the first of three, on July 26, and will speak about noise, air quality and traffic impacts at the other two scheduled meetings, on August 23 and 31.

Hunt has opposed the parkway for years. At first, he says, his motivations were self-serving: He worried the road change would worsen traffic and impact his own quality of life. Now Hunt claims to be sticking up for his neighbors, many of whom are low-income tenants in subsidized housing and immigrant families who might not have the time or resources to weigh in on the project.

“Act 250 is not a process for the common guy,” Hunt observes. “You have to have a lawyer and consultants.”

Before he retired, Hunt was executive director of the Vermont Housing Finance Agency, a nonprofit that “finances and promotes affordable, safe and decent housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income Vermonters,” according to the website. Pointing toward King Street from his front porch, Hunt says the blocks that will bear the brunt of increased traffic are some of the poorest in the city — with high rates of subsidized housing — and that higher-income homeowners in the neighborhood may move out if traffic becomes intolerable.

The traffic configuration at the Maple-Pine corner is currently so bad that it gets an “F” in the city’s ranking of local intersections, indicating “extreme delays” for motorists. But the Champlain Parkway solution will barely improve that grade. Even with a new stoplight and turn lane, the city anticipates the intersection would score a “C” grade during the morning commute and a “D” during the afternoon commute. A D grade indicates “long delays” of 35 to 55 seconds to get through.

Still, Hunt isn’t getting much of a rise out of people. The sentiment among many business owners, he says, is: What’s so bad about more cars passing my business? To which Hunt responds, If people think the parkway is too slow, they’ll avoid it altogether.

“Normally in Burlington, you should be able to get people to oppose anything. That’s just the way Burlington is,” Hunt says as a black Chevy Blazer lurches past, blaring Eminem through its tinted windows. “But that’s not the case here.”

Maybe that’s because most Burlingtonians support the idea?

“I’d say it’s because it’s been going on for so long, people don’t believe it’s going to happen,” Hunt replies. “A lot of people confuse it with the Circ Highway, and they think, Isn’t that project dead? The governor pulled the plug.”

Hunt and others challenge justifications for the highway by pointing out that the actual number of trucks driving through South End neighborhoods is unknown. City officials estimate that of the roughly 14,000 daily vehicular trips, 10 to 15 percent — between 1400 and 2100 trips per day — are tractor-trailers hauling lumber, heating oil, stone and salt to industrial areas off Pine Street.

Hunt doesn’t believe the information was deliberately omitted from the application but says, “It seems like we’re missing a key piece of information.”

Public Works engineer Carol Weston, the project’s local overseer, explains that while no actual counts exist, it’s typical to estimate truck trips as a percentage of overall traffic, and that Burlington has done exact counts in the past. “It’s fair to say that there are a lot of trucks,” she says, adding that she believes truck traffic has stayed level over the last several years. “It’s not the majority of traffic, it’s just that their impact is heavier — they’re loud and have loud braking systems.”

Weston stresses that the parkway, which is 95 percent federally funded, won’t increase overall traffic to the city but will simply divert more vehicles — about 2000 per day — from Route 7 and other roads onto the parkway and Pine Street.

How about bikes? Another bone of contention is the lack of dedicated bike lanes, crosswalks and sidewalks on some stretches of the parkway. As submitted, the parkway’s design removes some dedicated bike lanes to build wider shared-use lanes and left-hand turn lanes, plus it leaves gaps in the sidewalk system and shows six intersections without crosswalks, according to Burlington-based alternative transportation group Local Motion.

At the congested intersection of Pine and Maple, for example, a traffic signal will replace stop signs, and traffic lanes will narrow to accomodate a left-hand turn lane for trucks heading to and from Battery Street. Ditto for the intersection of Maple and King.

That could present a problem, because, in order to win Act 250 approval, the city must show that the parkway’s design conforms to its transportation plan, passed by the city council in March. Ironically, that plan designated portions of Pine Street as a “Bicycle Street” intended to give cyclists “priority treatment,” and other sections of the road as “Complete Streets” aimed at “accommodating all travel modes safely and efficiently.”

“Overall, the project is pointed more or less in the right direction,” says Jason Van Driesche, Local Motion’s education and safety manager. “As always, the devil is in the details, and there’s a whole bunch of places where there are critical gaps in how things are laid out.”

Weston says the city will look at the transportation plan and adjust the parkway design to the extent possible to meet the benchmarks.

Who else loses with the new road’s configuration? Residents on Home and Flynn avenues have long complained of rumbling trucks cutting through their neighborhoods from Route 7 at all hours. They’re the potential winners here. Meanwhile, homeowners living near the proposed parkway are likely to inherit that noise and air pollution.

“The mission seems to be to remove excess truck traffic flow from a few neighborhoods,” says Thea Lewis, who lives on Home Avenue near the proposed parkway. “The problem is, it will redistribute a worrisome volume of traffic in a way that impacts even more of the community — effectively throwing a noose of heavy traffic and bad intersections around an even larger geographical area.”

Weston acknowledges the parkway will impact some neighborhoods more than others, but stresses the project’s overall goal: to improve everyone’s driving experience by moving traffic more efficiently in and out of downtown. According to its Act 250 filing, the city’s traffic modeling predicts the Champlain Parkway will decrease traffic on Maple Street by 1300 vehicles a day, while King Street traffic will go up by 1500 vehicles a day. If everything goes as planned, Weston says traffic will move more efficiently through Allan Hunt’s neighborhood — making the view from his front porch look more like a normal city street and less like a parking lot.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.