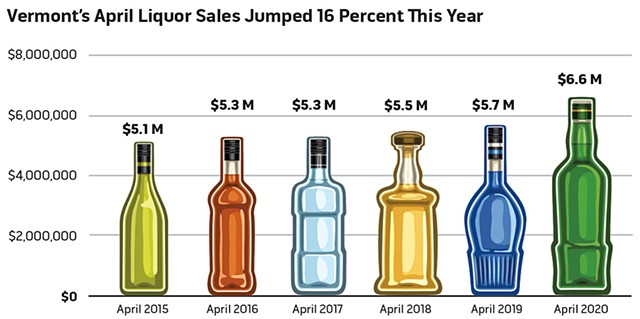

- Source: Vermont Department of Liquor and Lottery

When Gov. Phil Scott's finance commissioner briefed lawmakers last week on a plan to balance Vermont's beleaguered state budget, the news was mostly sobering. But there was a chaser. "For better or for worse," Commissioner Adam Greshin said, Vermonters appear to be boozing it up while hunkering down during the coronavirus pandemic — leading to an uptick in state liquor revenue.

According to data provided by the state Department of Liquor and Lottery, retail sales of distilled spirits were up nearly 16 percent year over year in April — the first full month during which Scott's stay-at-home order was in place. The binge contributed to an unexpected $4.6 million revenue bump in the fiscal year ending next month.

"I would be inclined to say that personal consumption has increased," Liquor and Lottery Commissioner Patrick Delaney told members of the Senate Appropriations Committee later last week. "For all intents and purposes, we're riding the wave."

While some retailers have managed to catch that wave, many in Vermont's sprawling alcohol industry — brewers, distillers, vintners, restaurants, bars and distributors — have been swamped by it. Though emergency orders permitting takeout and delivery have helped some in the sector, the temporary rules have not made up for the closure of more profitable portions of the business, such as brewpubs and tasting rooms.

"It's the big guys who are the winners. It's the premium local brands that are getting hammered," said Bret Hamilton, owner and manager of Richmond's Stone Corral Brewery. "Understandably, shoppers are being very cautious with their money."

Indeed, preliminary state data suggest that shoppers are gravitating toward what Delaney refers to as "value brands," such as Jack Daniels, Absolut and Tito's. They are buying in larger quantities, the commissioner said, to "fill the pantry" during the pandemic. Sales of 1.75-liter bottles were up by close to 29 percent in April compared to last year, while sales of 750-milliliter bottles increased by just 2 percent.

According to Delaney, that's a reversal of a long-term trend toward buying smaller quantities of higher-quality liquor.

"Spirits are an investment," said Ryan Christiansen, president of and head distiller at Caledonia Spirits. "A lot of the more interesting spirits depend on the customer browsing by picking up the bottle, reading more about it and thinking about it." Consumers engaging in curbside liquor pickup are more likely to stick with "the brands that you know the store is going to have in stock," said Christiansen, who serves on the board of the American Craft Spirits Association.

That dynamic has benefited Vermont's better-known beverages, such as Caledonia's Barr Hill Gin, but it's hurt the state's many smaller distillers. "Most of our members are down 50 to 60 percent," said Distilled Spirits Council of Vermont president Jeremy Elliot, who is also the co-owner and president of Smugglers' Notch Distillery. "People are not willing to gamble on something they're not familiar with."

Though the state does not track beer or wine sales, a similar dynamic appears to be taking place in those sectors. "We have definitely seen an uptick in larger-format packaging," said Ryan Chaffin, director of marketing and business development for Farrell Distributing, the state's largest distributor.

Those who used to buy 12-packs of national brands are now picking up 30-racks, he said, while those who favored four-packs of Vermont craft beer are looking for 12-packs. According to Chaffin, boxed wine, such as Bota Box, also "has had a good run."

Vermont's larger brewers appear better poised to weather the storm.

Lawson's Finest Liquids took "a pretty significant hit" when it closed its Waitsfield taproom in March, according to founding brewer and co-owner Sean Lawson. It also lost out when bars and restaurants in the eight other states it serves closed down. "But really the biggest part of our business for distribution is the retail sales, and thankfully those are up at retail stores across all nine states," he said. "Overall, we're holding steady. We're doing OK."

After halting beer production for two weeks in order to reduce inventory, Lawson said, the company has achieved a new equilibrium and honed its drive-through beer pickup system in Waitsfield. "What's remarkable is how steady it's been for the past eight weeks," he said.

At the same time, Lawson fears for his smaller peers. "The ones who are most affected are those that sell primarily through their taprooms and on-site sales," he said.

According to Hamilton, only 25 to 30 percent of the beer that Stone Corral produces is sold at the Richmond brewpub, but it accounts for 75 to 80 percent of the company's revenue. That's because direct sales cut out distributors and retailers. "You have to be able to sell your own beer through your own taps as a small brewery just to be a viable business," Hamilton said.

Brewpubs and distilleries are also important venues to hook future retail customers. Close to 85 percent of those who visit Smugglers' Notch's shuttered tasting rooms in Burlington, Waterbury and Jeffersonville are tourists, according to Elliot. "So if the tourists don't come back, I have some serious decisions to make in the next couple of months," he said.

While liquor sales are up at many of the state's 76 authorized retailers, there appears to be some regional variation. According to Delaney, stores in the Connecticut River Valley are doing better than their counterparts elsewhere in Vermont. He said that could be because some state-run liquor stores in neighboring New Hampshire have closed, while all but two of Vermont's have remained open.

Dan King, assistant manager of Norwich Wines and Spirits, has another theory. "The state liquor stores in New Hampshire are often crowded, especially in the evening," he said. "Maybe it's reassuring to the average customer that we're not letting anyone into the store."

While sales are up at King's store, the Beverage Warehouse in Winooski is having a different experience. Thirty percent of its sales typically are made to restaurants and bars, according to co-owner George Bergin. It also relies on events that draw a crowd, such as weddings and graduation parties. "Without the tourists, without the college kids, without people getting married, the numbers overall are definitely down," he said.

Though food and beverage retailers were never forced to close their doors, many, including the Beverage Warehouse, did so for health and safety reasons. (The store printed black T-shirts to celebrate its designation as an essential business. They read: "The Bevie: Essential AF 2020.")

Co-owner Jen Swiatek said curbside sales helped ward off layoffs but resulted in "four times the work and half the money." The Bevie recently allowed a small number of customers back into the store.

Vermont restaurants, which have been particularly hard-hit by the pandemic, have tried to make the most of the temporary rules allowing takeout alcohol sales. The Great Northern in Burlington's South End is offering its signature cocktails — including the Maple Mad Fashioned — in glass maple syrup containers. Though the to-go booze biz is hardly making up for an overall drop in sales, according to chef and owner Frank Pace, "It helps customers remember what they loved about our bar."

Taco Gordo, in Burlington's Old North End, didn't immediately offer takeout drinks after it shifted to curbside pickup and delivery, according to owner Charlie Sizemore. "We took two, three weeks, sort of figuring out how we were going to manage that in a safe and responsible way," he said.

Now, its Takeout Marg LOL is helping to keep the restaurant afloat. "It's like a life raft that we can sort of sail into safe harbor," Sizemore said. He's hoping the state will allow his and other establishments to continue selling to-go booze through the duration of the economic downturn so that he can avoid opening up his dining room until it's safer to do so.

Lawmakers did express concern about the size of some to-go orders during last week's Senate Appropriations hearing. "I've never seen a 32-ounce cocktail served to someone at a Vermont restaurant or bar," Senate President Pro Tempore Tim Ashe (D/P-Chittenden) told Delaney. "Obviously, you don't know how many people that's going home to."

Delaney responded that his department was worried about restaurants delivering alcohol without checking identification. "In other words, drop the product, ring the doorbell and head back to the vehicle," he said. "That, to us, is a major concern in terms of access to minors."

Sen. Dick Sears (D-Bennington) also noted that an increase in alcohol consumption could lead to an uptick in alcohol-related crime, such as drunk driving and domestic violence.

In fact, early data from the Vermont State Police and other law enforcement agencies using the same records management system show a drop in intoxication and DUI arrests from March 1 through May 15 compared to the same period a year earlier. Police reports mentioning "intoxication," "intoxicated" or "DUI" declined from 624 to 507, according to data provided by Vermont State Police Sgt. Jay Riggen.

Tony Folland, clinical services manager for the state Department of Health, said it was too soon to know how Vermonters' drinking habits have changed during the pandemic and how that might affect their health. Despite the dearth of data, he said he was concerned about those who may be using alcohol to cope with social isolation or preexisting anxiety or depression, as well as older Vermonters who may be mixing alcohol with medications.

"If you're questioning whether it's concerning or you're feeling like there's something wrong, reach out, because there is care available," Folland said.

Those in the booze business, meanwhile, are encouraging Vermonters to spend their money locally whenever possible in order to keep them and their peers in business. Christiansen of Caledonia Spirits noted that farmers rely on distillers and brewers, who rely in turn on bartenders. "There's kind of a ripple effect that begins by taking the bartender out of the equation," he said.

"We are so interconnected," said Swiatek of Beverage Warehouse. "We're not just competitors. Business is not just business in Vermont."

Disclosure: Tim Ashe is the domestic partner of Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly. Find our conflict-of-interest policy here at sevendaysvt.com/disclosure.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.