- Courtesy Of Rob Swanson

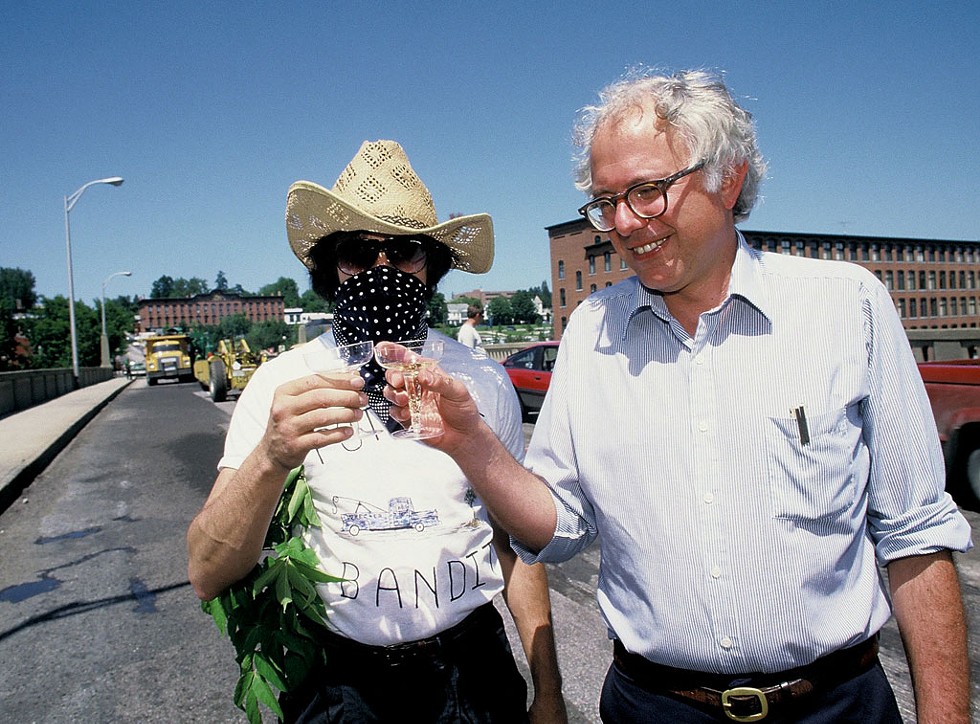

- Pothole Bandit and Bernie Sanders, 1986

It's difficult to pinpoint the year when Burlington began racking up accolades as one of the nation's best cities for X, Y or Z. Townies who've been around a while, however, will generally agree that it was during Bernie Sanders' tenure as mayor that the phrase "quality of life" became deeply etched in the Burlington brand.

I have to confess: In the summer of 1986, in the thick of Burlington's renaissance, I didn't appreciate what Sanders and his comrades were doing for my hometown. I'd just graduated from college in upstate New York. While the speaker at my commencement — an executive from the Rand McNally map corporation — had exhorted my peers and me to "be eccentric and bellow," I hadn't figured out how. I was back home in Burlington, doing temp office work and drinking in the same bars I'd frequented in high school.

- Courtesy Of Rob Swanson

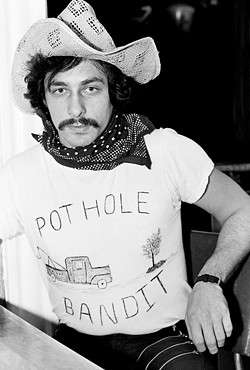

- Pothole Bandit Bruce K. Ploof, 1986

Apparently, I wasn't the city's only restless soul. As I unfolded my copy of the Burlington Free Press one day, a headline below the fold caught my eye: "Pothole Bandit Plants Trees in Protest of Roadway Ruts."

The article reported that, in the wee hours of the previous day, someone had filled three downtown potholes with spruce saplings. The vege-lante left signs reading, "Potholes of Burlington, Beware. (Signed) The Pothole Bandit."

When I looked up from that paper, my city had been transformed into a comic-book setting — complete with its own superhero. Or was he a supervillain? Or was he a she? I didn't care. What mattered to me in that moment was that some eccentric had bellowed. Maybe there was hope for me yet.

Reading on, I learned that the Pothole Bandit was a male — as he had revealed in a call to WQCR DJ Louie Manno on the morning of his road raid. In the year or so that Manno had been on the air in Burlington, he and cohort Jim Condon had developed a reputation for broadcast buffoonery. Their "Leave It to Bernie" segments regularly parodied the mayor.

When the Pothole Bandit told Manno what he'd done, the DJ was skeptical. In a recent interview, Manno recalls telling the anonymous caller, "You're full of it."

But Condon confirmed the plantings — on three city streets — with the Burlington Police Department, which had been fielding calls about them all morning. And Manno sensed an opportunity for live-radio antics. "Any time something had possibilities to put on the air and milk, I would be all for it," he says.

Manno figured the logical, mirthful next step would be to put the Pothole Bandit and police chief Kevin Scully on the air simultaneously. Scully, a pioneer in community-based policing, played along. He called in and upped the ante, proposing that he and his nemesis meet in person.

Manno knew the perfect location for the showdown: Perkins Pier. Out in the open. No ambushes. No funny business. Well, maybe some funny business.

The following morning, a gray day with a stiff wind blowing in off the lake, the lawman and the outlaw faced off. Scully sauntered in from the west. The Pothole Bandit swaggered in from the east — decked out in a straw cowboy hat, sunglasses and a bandana mask. In his holster he carried a tree branch. With Manno, Condon and other media types looking on, Scully and the Pothole Bandit shook hands and began hashing things out.

Their meeting lasted only a few minutes. In WCAX-TV footage acquired for this story, the adversaries look anything but adversarial. According to Scully, the terms of the negotiation were straightforward. "We agreed that he wasn't going to do this anymore," Scully says with a laugh. "Because his insistence on doing this was very likely going to cause an accident. I think there were a couple of close calls."

In the spirit of the occasion, the chief agreed not to disclose the Pothole Bandit's true identity. That reveal would come soon — too soon for the Bandit.

- Courtesy Of Rob Swanson

A couple of days later, the masked man made the mistake of setting up a Free Press interview at the North Street home he shared with his parents. The reporter spotted him as he was putting on his Pothole Bandit disguise, which his mother had helped him make. This was how the name Bruce K. Ploof, belonging to a then-28-year-old cab driver, made its way into local legend.

"That was a screwup," Ploof says now of being caught with his bandana down. "I wanted to play this thing out a little longer."

Whether he liked it or not, the unmasking fanned a media fire that spread to news outlets nationwide. The Pothole Bandit story was one of those quirky, quixotic Vermont yarns that played so well outside the state. And still do. Just ask the Bernie for President campaign staff.

Whatever the Pothole Bandit symbolized on the national scene, locals embraced Ploof's lighthearted brand of civil disobedience. "It was really fun, and it was good-humored, and there were laughs," says City Councilor Sharon Bushor (Ward 1), then public works commissioner. "Everyone in the community got it, and everyone in the community, I think, enjoyed how it ended."

That included Mayor Sanders, a man not known for his sense of humor, at least in public. On July 12 — just a few weeks after the Pothole Bandit's evergreen escapade — Sanders, with Bushor at his side, offered Ploof a mayoral pardon on the Winooski Bridge. According to an article in the New York Times, Sanders also pledged $1 million toward road repairs at the meeting.

The whole episode had a curious effect on me. Like many people, I'd found the Pothole Bandit story kind of enchanting. I stopped fretting about being stuck in Vermont, to coin a phrase, and started appreciating the magic that can happen in a small city where even the big shots aren't too big to poke a little fun at themselves.

Yet when the Pothole Bandit comic-book story reached its last page, I yearned more deeply than ever to know what life was like outside my margins. By autumn, I was bound for destinations as far from Vermont as a person could travel. I'd wander for a decade, long enough to figure out where I wanted to land for good: Burlington.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Bruce K. Ploof with his grandchildren

Turns out, the Pothole Bandit also rode off into the sunset for a spell. Ploof hit the West Coast, and then the Midwest, before family ties — to his daughter Danielle and grandchildren Jaiden, Jocelynn, Julianna and Jasmine — called him home.

When he thinks back to the summer of 1986, Ploof recalls mostly the upsides of his notoriety. "I met a lot of girls," he says. A few beats' reflection reminds him that his momentary fame helped patch up a rocky relationship with his parents. He remembers Scully and Sanders as having treated him decently, and he's quick to call Manno "a good guy."

Ploof is a busy man these days. He works two jobs, one of which — in a twist nearly as implausible as a superhero battling potholes — is with the Burlington Department of Public Works.

He and I are in our fifties now, and the innocence of '86 is a fading shared memory. Only by straining my tired eyes can I see Burlington as a comic-book setting, a municipality in miniature, a microcosm, a metaphor. I accept the potholes, even the worst of them, as inevitable. We fill them without hope of filling them for good, just as we fight other endemic problems: drug addiction, food insecurity, violence against women and every other social ill we wish we didn't know.

Still, the Pothole Bandit's legacy lives on — for me, anyway — in the city's resolve to acknowledge the good things we have going here without taking them for granted. When people outside Vermont ask me what I think of Bernie Sanders, I tell them he was a good mayor full of great ideas whose regard for everyday people could take surprising forms. If they want an example, I share the legend of the Pothole Bandit.

And when I hit a pothole these days, I think of that guy who refused to let the city go.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.