- Caleb Kenna

- Rebecca Ayako Bennette

Middlebury College professor Rebecca Ayako Bennette thinks history has a public relations problem.

Since 2008, the number of undergraduates receiving degrees in history has fallen more steeply than any other major. In 2019, that number reached a historic low, according to the American Historical Association. Bennette doesn't blame students who choose different majors — she herself hated history in high school, when she associated the subject with painstaking memorization.

But as chair of Middlebury's history department, Bennette finds these trends concerning. So she's spreading the word that history is valuable, both to students and the general public. In her new first-year seminar, "History, Representation and the Graphic Novel," she uses comics to teach about historical atrocities, from slavery to the Holocaust. She's also on television. A specialist in 19th- and 20th-century Germany, Bennette is an expert commentator in the new Hulu docuseries "Hitler: The Lost Tapes of the Third Reich."

History, Bennette said, shouldn't be mistaken for a "pie in the sky" field. Insistent that "there are no useless degrees at a place like Middlebury," as she put it, she is a staunch advocate for the liberal arts. As a practical matter, historical pattern recognition can be useful for preventing modern-day human rights abuses, Bennette said. But more broadly, she believes that a liberal arts education can open doors for students in the same way it did for her.

"I grew up in a family with no money," Bennette said. "If I thought I was condemning [students] to a useless education that they were going to pay for, and then no job prospects, that would be morally unacceptable."

Bennette grew up in Youngstown, Ohio, the child of a Japanese immigrant mother. In first grade, Bennette remembers, a boy called her a racial slur. She came home upset and told her mother, who asked Bennette to think about whether she believed the boy's words. The incident was a heartbreaking but valuable lesson in self-worth, Bennette said. It would steel her for her first year at Johns Hopkins University, when her roommate put up a sign in their dorm room that read "No Japs."

"A lot of times, you have to forge ahead," Bennette said. "Even when you're saying things that people don't want to hear, even when people are treating you as if you don't belong."

Bennette is drawn to graphic novels, a medium she sees as giving voice to people who have been largely left out of history textbooks. The form, she said, allows for narrative experimentation that brings new meaning to familiar stories.

Presenting history through the lens of visual storytelling doesn't mean simplifying or trivializing atrocities, Bennette said.

"It's not a dumbing down of what's being taught. It's teaching it in a more accessible way," Bennette said. "If not enjoyable — perhaps that's not the right word when we're dealing with atrocities — it's always difficult, but at least engaging."

Bennette compares historical facts to Lego bricks: No two people will build exactly the same structure with the same blocks, just as history can be interpreted in a number of different ways.

She brought that philosophy to class during a recent discussion of Maus: A Survivor's Tale, a 1986 graphic novel by Art Spiegelman that tells the story of his Holocaust survivor father. Rather than lecturing from the front of the room, Bennette sat at a table with her 16 students and got them to do most of the talking. She asked a series of questions: What are the advantages of graphic novels as a medium for teaching history, and what are the dangers? How did the students feel about the novel's use of humor? If they had to put Maus in a bookstore, what section would they put it in, and for which age group would they recommend it?

The class seemed to agree on 10 years old as the minimum age, though there was disagreement about whether Maus should be classified as memoir, nonfiction history or historical fiction. Students also pointed out that the medium allowed Spiegelman to heighten symbolism through his illustrations.

"This kind of metaphor is not something that you would really be able to employ with writing," said one student, noting the novel's depiction of Jews as mice in reference to the Nazis' association of Jews with vermin.

"Victims of atrocities are humanized in graphic novels," another student added. "You just keep seeing that 6 million statistic [of Jews murdered in the Holocaust], but in the graphic novel, you see people with their families, living their lives."

Bennette also urged students to consider the historical context of the novel itself. Spiegelman initially had trouble publishing his work in the era of the superhero comic, when many critics thought graphic novels were structurally incapable of serious literary expression. But attitudes changed, and in 1992 Maus became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize.

"Now, no one's going to look twice when you teach this," Bennette said. "But when it first came out, people were like, 'It's trivializing. How dare you!'"

- Caleb Kenna

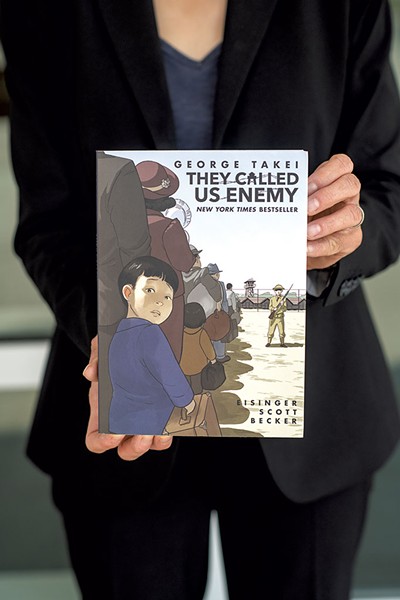

- They Called Us Enemy by George Takei.

Other graphic novels on Bennette's syllabus include They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, a memoir of the Japanese American actor's childhood experiences in an internment camp; Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga by Lee Francis, the story of a group of Native Americans murdered by white settlers in Pennsylvania; and Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, about sexual slavery perpetrated by the Japanese Imperial Army.

Bennette chose these works, she explained, because they highlight underrepresented voices in history. For example, Bennette said, the events of Ghost River have historically been called the Paxton Boys Massacre, named for the perpetrators who were known as Pennsylvania's most violent colonists. Bennette questioned that nomenclature. "They were men who murdered in cold blood a bunch of Native Americans — so why are we calling them boys?" she asked. Ghost River tells the story from the perspective of the Native American victims.

Middlebury first-year River Costello said he doesn't mind reading the dense tomes that typically make up a history course syllabus, but he was excited about studying the subject through graphic novels. He said he was surprised by the breadth and depth of the reading material.

"I didn't really think that there would actually be enough out there to make a class out of studying graphic novels," Costello said.

In class, Bennette asks some questions that do have straightforward answers. "How many of you think that we should try and stop human rights abuses, atrocities and genocides?" she frequently asks her students. Of course, every hand in the room goes up. Students who care about social justice ought to care about history, Bennette said.

She acknowledges that critics might deem her defense of the history degree as elitist or ignorant of the realities of crippling college debt. But she also rejects the idea that a history degree consigns people to a life of poverty. Students often don't end up working in the field they studied, she said, and history prepares students for high-paying careers in business management, education and law.

For college administrators, finances are also part of the programming calculus. Citing low enrollment and a budget deficit, University of Vermont administrators in 2020 proposed cutting more than two dozen academic programs from the College of Arts and Sciences, which includes the history department. The proposal was met with intense pushback, and most of the cuts have so far not been implemented. But budgets reflect an institution's values, Bennette said, and some seem too eager to cut the humanities first.

"It's not about cash; it's about investment," Bennette said. "An institution can have all the resources in the world. If it doesn't care, it doesn't care."

While the undergraduate study of history has taken a nosedive nationwide, some elite universities have bucked the trend. At Yale University, history was the most popular major for the class of 2019. At Middlebury, there are about the same number of history majors now as there were 15 years ago, according to Bennette.

As a first-generation college student, Bennette is no stranger to financial pressure. At Johns Hopkins, she had originally planned to study chemistry until a course on Western civilizations showed her that learning history wasn't simply memorizing a series of disjointed facts.

Education has meant everything to Bennette, who said she feels like an embodiment of the American dream. She was one day shy of accepting a spot at University of Chicago Law School when she decided to pursue a doctorate in history at Harvard University instead. Beyond her passion for the subject, the decision was partly financial: Law school tuition would have required loans, while Harvard paid her to get a PhD.

Higher education is at a crossroads, Bennette said, with the humanities under threat. In order to stay relevant, she said, academia needs to evolve with the times.

Her course is one way to reengage students by "meeting them where we are now, not where we were 20 years ago," Bennette said. "History is a moving target, and you've got to keep moving with it."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.