- Steve Legge

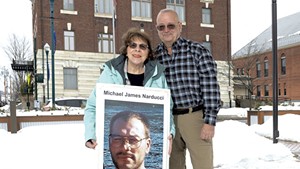

- Chantelle Blackburn

It might as well be midnight, so heavy are the rain clouds over downtown St. Johnsbury. Even the streetlights seem dull under their weight.

Chantelle Blackburn arrives a few minutes before 8 p.m. at the white Colonial overlooking Main Street. She unlocks the front door, slips inside and snaps the dead bolt shut, then ascends a dark stairwell up to the room where she will spend the next 13 hours.

The room is about the size of a dentist's waiting area and somehow less welcoming. Lamplight reveals two desks and a blanket-covered recliner. A countertop holds a microwave, a coffee pot and a sad assortment of snacks: Goldfish, SlimFast bars, Little Debbie chocolate cakes.

Blackburn has spent dozens of nights here over the past year and seems at home. She's wearing her "PJs": black tights and a sweatshirt that covers her tattooed arms. She kicks off her rain boots and drops her bags.

The room is hot and stuffy, but the electric baseboards still hum, controlled by a thermostat in the group home that occupies most of the building. Blackburn cracks the windows to take the edge off, and the sound of tires on wet pavement spills in.

She sits down in a gaming chair, opens her laptop and checks the time. At precisely 8 p.m., a switch flicks somewhere in the digital universe. Just like that, she is thrust back onto the front lines of Vermont's fight against despair, a post she will hold through sleepiness and boredom, until reinforcements arrive in the morning. For now, though, the front is quiet. She unpacks her bags and settles in.

At 9:30 p.m., the phone rings. Blackburn removes one of her earrings.

"Thank you for calling Lifeline," she says, pressing the phone against her head. "This is Chantelle."

'High Risk'

Pause here and zoom out, far enough to see a map of the U.S. in the mind's eye, and the phone that Blackburn answers appears among a constellation of shimmering red dots. Each represents one of the more than 200 call centers that make up 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

The 24-hour service, chronically underfunded since its inception in 2005, received a $400 million federally funded reboot this summer in response to a surge of mental illness in the U.S.

The money allowed the patchwork of call centers that run the hotline to hire more staff and funded the creation of an additional two dozen phone banks. The infusion also allowed the hotline to transition from the 10-digit number that most people know from warning labels on TV episodes to the far easier to remember "988."

Since mid-July, all calls and texts to 988 have been routed to the hotline; federal officials hope the number will one day be thought of as the 911 for mental health crises.

The hotline received 255,000 calls in August, a nearly 50 percent increase over the same month last year. Vermont experienced a similar jump: The 670 calls made in August were double last year's total.

Like all call-takers, Blackburn received training on how to help calm emotional situations over the phone and connect those in acute crisis to more comprehensive supports, including, in rare cases, emergency responders. Calls are routed to local crisis centers based on area codes, then forwarded to national backup centers if they go unanswered. Answering locally is preferable because counselors generally have a better idea of what services exist in their area.

Vermont has two 988 call centers run by nonprofits better known for their work contracting with the state to provide mental health, substance-use and disability-related services. The Northwestern Counseling & Support Services in St. Albans handles all calls and texts from 9 a.m. through 8 p.m., while the Northeast Kingdom Human Services in St. Johnsbury is responsible for any contacts between 8 p.m. and 9 a.m.

Blackburn helps supervise the agency's four dedicated call-takers and fills in herself whenever needed. She's lately worked three shifts a week on top of her day job as an enhanced crisis case manager, a grueling schedule made no easier by the fact that it's impossible to know how each shift will go.

The phone rings so often some nights that she can barely find the time to eat. Other shifts pass by with hardly a call. But even then it can be difficult for Blackburn to relax, knowing that at any moment she might need to talk someone down from the edge.

Roughly half of the 800 calls that Blackburn and her colleagues answered between July and September were deemed "high risk," meaning the person not only expressed suicidal thoughts but also said they had a plan to carry them out. Only 24 calls resulted in the dispatch of police or EMTs, however. Counselors managed to talk down the rest of the callers over the phone, according to Josh Burke, the NEK agency's director of emergency services.

"We have the power of time," said Burke, who oversees the hotline program. "We'll be on with them as long as it takes. Them staying on the phone is a connection to life."

Of course, not every caller is suicidal. Many speak about grief, anxiety, addiction or trauma. Some just want company.

Blackburn can usually tell what she's facing within seconds of picking up the phone.

"You can feel it in their voice," she said.

9:30 p.m.

The first call of the night is from a young woman who has googled "Who to call for a panic attack?" She tries to explain what is wrong but struggles to speak amid sobs and rapid breaths. She apologizes repeatedly.

"It's OK. It's OK," Blackburn softly replies. "Don't apologize. I'm glad you're here."

Blackburn advises the caller to take some deep breaths. "In through your nose, out through your mouth," she says. "Feel the anxiety leave when you exhale."

The technique seems to work: The young woman calms down enough to explain that she is anxious about an upcoming appointment for some unresolved health issues. Blackburn hears her out and asks if she has any coping strategies. She personally finds that listening to classical music helps ease her mind, she tells the caller. The two are eventually laughing. By the end of the 40-minute conversation, the young woman agrees to schedule a follow-up phone call.

Blackburn catches up on work emails, then turns on a Netflix trivia game show called "Bullsh*t," hosted by comedian Howie Mandel. At 10:30 p.m., the ringing phone interrupts the first episode. A young man is worried about a friend who texted him and said she did not want to be alive tomorrow, then stopped responding. But the friend finally texts him back a minute into the call.

"Do you want to call her and see if she'd be willing to talk to us?" Blackburn asks. He says he will. "Great," Blackburn says. "Call back if you need me."

An hour and two "Bullsh*t" episodes later, the phone rings again. Blackburn pauses Mandel mid-sentence. An older woman explains through tears how she lost her husband a few years ago and is struggling with a new relationship. Blackburn listens and tries to validate her feelings: "Your life changed in an instant," she says. "The grieving, the confusion? Those are normal emotions. Don't beat yourself up." The conversation gradually shifts to more benign matters: pets, family, travel. The woman says she feels better. She, too, agrees to a follow-up call. She tells Blackburn before hanging up: "Thanks for helping me — and listening."

To Feel Entirely Alone

Blackburn never planned to get into crisis work.

She worked in hospitals and nursing homes for years, then switched professions and became a civil engineer. A pandemic-era shift to remote work allowed her to move from North Carolina back to Vermont to be closer to her father, who's battling cancer. When her employer mandated a return to in-person work last year, she applied for a job at Northeast Kingdom Human Services, which was just launching its suicide prevention hotline.

The opportunity appealed to her, she said, because she knew better than most what it is like to feel entirely alone in the world.

Blackburn was 15 when she met the 20-year-old man who would become her first husband; she said she experienced verbal and physical abuse during their 15-year relationship. She has since remarried and now strives to support other victims of spousal abuse through a Facebook page she runs anonymously. She's helped other women escape abusive relationships, she said, and is taking psychology classes at the Community College of Vermont with a goal of one day working with domestic violence victims full time. She's also writing a memoir about her experience and has typed out 100 pages so far, with "much more" to say.

"I hope I can empower more women," she said.

1:30 a.m.

Blackburn is in the bathroom when the phone rings again. She hustles back to her desk.

The caller, a young woman, tells Blackburn that she has been having suicidal thoughts and would like to go to the hospital. Blackburn offers to send an ambulance, but the caller wants to first ask friends whether they are willing to take her. A few moments later, voices spill out of the phone pressed against Blackburn's ear, loud enough to be heard from 10 feet away. "What the fuck are you doing?!" somebody yells. "Hang up the phone!"

The line goes silent.

Blackburn can't believe it. "They yelled at her," she says, shaking her head.

Blackburn rests her chin on her thumbs and stares at the paused Netflix screen, weighing her options. "I'm not supposed to call back," she says. "But everything in me is telling me I should." She goes with her gut. The call goes straight to voicemail. She sighs.

"All we can do now is hope that she calls back if she needs us," she says.

She leans back in her chair and resumes the game show.

Seven more hours.

'You just want everyone to be OK'

Blackburn vividly remembers the first time she had to connect a caller with emergency services. An older veteran in southern Vermont called in and said he no longer wanted to live. She heard a click, followed by another. "I can't get this damn gun to fire," the man muttered.

Blackburn thought about her son in the Navy, how he was trained to respond to orders. She told the man in her sternest voice to put down the gun. He complied. She told him to disassemble it. "Yes ma'am," he said. She convinced him to drive to the Veterans Affairs hospital in White River Junction and stayed on the phone until she heard the ER staff take over in the parking lot. She hung up the phone, walked outside and cried.

Turnover has been a constant challenge for suicide hotline call centers over the years, a symptom of the same low-pay, high-stress cocktail that has long plagued their counterparts in 911. Call-takers routinely burn out within a year of taking the job. Many centers have open positions and manage to staff the phone lines only with the help of volunteers.

The switch to 988 this summer raised the stakes. Some centers were forced to create a dozen or more new positions to handle the increased demand. Those unable to quickly fill the new posts reported a spike in the rate of calls sent to backup centers.

The story has been different at Northeast Kingdom Human Services, at least so far. All five of its call-takers, including Blackburn, have worked the line for at least a year. And though calls that come in while they're already engaged get booted to a backup center, they've still managed to answer more than 80 percent of calls since the 988 switchover.

A pay-based retention incentive has helped keep call-takers around. They earn $20 to $25 an hour as a baseline and receive an additional stipend every quarter worth $3 for every hour they worked. That bonus works out to about $6,000 a year for a full-timer.

Blackburn said she has tried to create an environment in which it's OK not to be OK. She talks to her colleagues about compassion fatigue, the psychological phenomenon in which a person trying to help someone through a problem begins to internalize the distress. She accommodates anyone who needs to take time off. "You're hearing crisis every day, every day, every day," she said. "You have to make time for yourself. You have to regroup."

Blackburn has found her own ways of coping. She's part of a Christian women's support group and reads the Bible. She has a nightly routine in which she writes down a single word in her journal to describe a challenge she had that day and how she overcame it. She listens to classical music — lately, Bach.

For weeks after the veteran called, Blackburn worried the phone would ring again and she'd hear another person try to kill themself. A year later, her relationship with the phone remains complicated.

"I want the phone to ring because I want them to know I'm here," she said. "But every time it does, it means somebody's in crisis."

She likes to imagine on the slow nights that everyone is getting along just fine without her. But she knows better. Ninety-three Vermonters died by suicide in the first eight months of 2022, according to the latest state data. The number doesn't yet include the 21-year-old Hazen Union High School athletic director who killed himself in October. Or the 12-year-old boy who died last month after trying to hang himself on a school playground located less than half a mile from the St. Johnsbury office.

Blackburn's hardest moments these days come not during the calls themselves but afterward, she said, when the adrenaline has subsided and she's left alone with her thoughts.

"You just want everyone to be OK," she said. "But you can't control that. You can only control that one call."

3:30 a.m.

Blackburn is back on the phone with the widow, who is struggling again. They cover much of the same ground, but Blackburn shows no sign of impatience. The two speak for another half hour and sound like old friends by the end of the call. "Get some sleep," Blackburn says.

At 6:40 a.m., a young woman calls in from her workplace's parking lot. She is anxious and needs to talk to someone, she says. The call does not last long — her shift begins soon — but Blackburn talks her through a breathing exercise and tells her to call back anytime.

Blackburn remains at her desk, attentive, but the phone doesn't ring again. Sunlight spills in the open windows, followed by the sound of laughter and scuffing shoes — kids on their way to school. The rain that has been falling overnight turns to snowflakes that melt upon reaching the ground.

At precisely 9 a.m., a switch flicks somewhere in the digital universe. Blackburn's night watch is over. She gives the room a final once-over, then walks down the stairwell and through the front door, locking it behind her.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.