- Todd Davis with wife Shelly and sons Nathan (second from left) and Noah in 2007

Whether it's on blogs, in social media comments or playgroup conversations, there's no shortage of public dialogue between moms when it comes to parenting issues. The conversations dads have about raising kids are less conspicuous. What do dads talk about when they talk about parenting? We asked two local men who are new to the fatherhood thing — Sean Prentiss of Woodbury and Conor Stinson of Cornwall — to interview a more experienced father, whom they admire, about being a dad. Here are their candid accounts of those conversations.

— Alison Novak

The Act of Daily Living:

Sean Prentiss interviews Todd Davis

- Sean Prentiss with daughter Winnie

On a beautiful April day, Todd Davis and I strap on snowshoes to hike Solstice Mountain, the backbone of Woodbury, Vermont. Todd lives near Altoona, Pa., and is here to give a poetry reading from Winterkill, the latest of his 14 books. Todd and I met at a writer's conference four years ago. He is primarily a poet and teaches at Penn State Altoona, and I'm a creative nonfiction writer and a teacher at Norwich University. In the years since we met, our friendship has evolved to include hunting, the outdoors and, in the three months since my daughter was born, fatherhood.

As we hike through the shallow snow at the base of the mountain, I think of the time I visited Todd in Pennsylvania in April, exactly a year ago. We biked Lost Mountain and fly fished Bells Gap Run. But mostly I remember his wife, Shelly, and Todd's two sons, 22-year-old Noah and 19-year-old Nathan. I reflect on the way that Shelly invited me into their house and into their family; the way Nathan, then a high school senior, joined us in conversation and acted like a son, a friend and an adult to Shelly and Todd; and the way Noah taught me to fly fish. When I told him that he should go and catch some fish rather than wait around for me to catch my fly on some tree leaf, he said, "I'd rather help you catch a fish than catch one on my own." As I fall into reverie about Todd's family, I think about my own daughter — Winter Eve — sleeping in my wife, Sarah's, arms. I wonder what Winnie will be like when she's a young adult like Nathan and Noah. Can I raise Winnie as well as Todd and Shelly raised their sons?

We pause at White Rock Cascades, spring thaw tumbling its way over stones. "I hope Winnie loves the outdoors like Sarah and I do," I say.

With water chattering, Todd says, "When I was a boy, we had a hundred acres of woods behind our neighborhood. There was an abandoned blueberry patch, ponds, dirt trails to ride, deer trails to follow. I was allowed hours unsupervised to build forts, to run around, and, when I was tired, to lay down and be still, to look at the sky, the stars."

I'm reminded of one of Todd's poems: "How better to drift / toward another world but with leaves / falling, their warmth draping us, / our stomachs full and fat with summer?" And I'm reminded of my own childhood in Pennsylvania — the Delaware River and an old ridge of hardwoods, and time to explore both.

Todd continues, "Where we live, there's a few hundred acres of woods that border the Little Juniata River. Once the boys were old enough and we had talked to them about the potential dangers — rattlesnakes, the river, what plants were poisonous — we let them go. We would worry, but both boys learned about trees and plants, animal behaviors, and wild edibles."

I imagine hiking with Winnie in a year, showing her wild leeks that grow along our vernal creeks, pointing out deer tracks in the mud. "How did you get Noah and Nathan to love the woods so much?" I ask.

As we hike upwards, Todd says, "We took the boys into the woods when they were not a year old yet. We tried to make such excursions fun. Now that the boys are older, they'll ask me to go fish for brookies, to pick raspberries, to explore a water gap, to find a seep. When we are together in these places, we talk about deeper things."

What could be better than to have Winnie ask me to explore? I dream of wandering these woods when Winnie is a teen, talking about trout lilies and trilliums, but also college, dating, her fears, her dreams.

Too soon, we're a third of the way up Solstice Mountain. We can either head down to my woodstove burning back late winter or keep hiking. Todd says, "I always prefer hiking. And this mountain is gorgeous."

I nod. I knew Todd would appreciate Solstice Mountain because his poetry is laced with encounters with animals, deer hunting and fly-fishing stories. His writing shows a man who spends hours each week in the woods. But not only does Todd spend time outdoors, he spends time writing. Todd is nothing if not prolific, which is something I worry about. How can I balance being a father with being a writer?

"Writers are fairly obsessive people," Todd says, as we gaze upon a smaller, more hidden, cascade — and he is right. "We become passionate about something and find ourselves trying to put language to it. But because I wanted to be a good father and husband, I realized I would have to say no to many activities. I couldn't change the fact that I needed and wanted to spend time with Shelly and the boys, wanted to work out regularly, couldn't give up being in the woods. So what could I give up? Going to bars; going shopping; watching television; surfing the internet; texting; being on Facebook. I've never owned a cellphone."

As I watch our little cascade, I wander off into another poem of Todd's that deals not with what he has given up but with what he has found: "the sound / of creek bumping against pushed up gravel: / a change of structure bending, / the plummeting of water slackened, guided / and gilded by slivers of light etched / with hemlock needles and fir boughs, / with a shadow-show of alder cones reformed / into a pool of the coldest clarity."

As we stare into a pool of coldest clarity, Todd continues: "When the boys were little, I did a lot of my writing after reading to them before bed. Once they were in elementary school, in the morning after I put them on the bus, I would sit down to write."

"That's what I do, too," I say. "I write before Winnie and Sarah get up."

"But I must say," Todd continues, "as much as writing means to me, my relationships with Noah, Nathan and Shelly mean more. I would never sacrifice those relationships for writing, so I had to figure out how the two could coexist."

Todd and I continue our ascent. Soon, our trail peters out. As we make the short, steep push to the summit, I ask, "What lessons did you learn as a father that might help me raise Winnie as well as you and Shelly raised your boys?"

"The way your child will become their own person is mysterious," Todd says. "Because you and I like to come up with a game plan that will bring about best possible outcomes, because we believe perseverance pays off, we can fool ourselves into thinking we can 'control' who our child becomes."

Todd continues, "What I've learned is that being in relationship with your child daily, talking with them openly and honestly, that's the key. When they're suffering, they will come to you, as they do each day."

We reach the peak. Solstice Mountain is not a grand mountain, but it is our mountain. We gaze across Vermont, all sticks and twigs and melting snow at the end of winter. Todd resumes, "Instead of assuring Winnie that you will magically make everything alright, talk about ways to address the problem, talk about outcomes. Apologize when you screw up. It's not a sign of weakness."

Unfortunately, Todd has a plane to catch. Fortunately, I have a beautiful baby girl waiting below. So we turn toward home. Before we trudge down the mountain, I ask, "Got any final advice for a new father?"

As we glance down upon Solstice Lake and the small home where Winnie sleeps, Todd quietly says, "The biggest joy is simply to be in our sons' presence, to share with them their struggles and successes, witnessing their transformation into men, seeing that the values Shelly and I hoped to instill in them — care for the earth, care for creatures (human and nonhuman), a recognition of the beauty that surrounds us, humility about our place in the universe — that these values are important to them as well."

Todd, eyeing this landscape, continues. "On a basic level, I take joy in making dinner for them, watching them play basketball, fishing with them, reading a poem aloud to them, or listening to them read one to me. In other words, the act of living daily together is a profound joy."

Todd and I step off the peak. We've got to get Todd to his plane. We've got to get me back to the act of daily living with Winnie.

A Constantly Changing Dynamic:

Conor Stinson interviews Marty Feldman

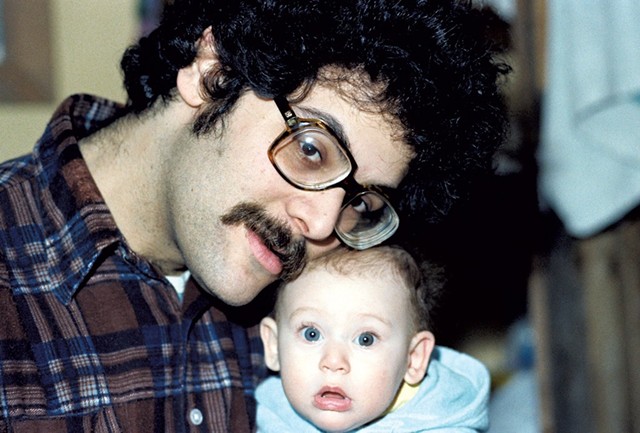

- Marty Feldman with daughter Claire in 1980

I was just getting used to living in Vermont again when I was asked to interview another dad about parenting. I first moved here in 1998 as a teenager and met my wife, Ellen, at Middlebury College. In October of 2015 we became parents to our daughter, Evie. Not long after her birth, we decided to return to Vermont after a decade living in Brooklyn and North Carolina, in part to be closer to my mom and her partner, Marty. Since last March, I have been caring for Evie as a stay-at-home dad. Our transition from an urban to a rural environment means that instead of wandering around city parks, Evie and I pass the days in the yard and woods, playing in puddles, and learning about birds and the art of tick detection.

Marty moved to Fletcher in the late 1970s and has been living in Vermont for close to 40 years now. He and my mom have been together for eight years. He is always generous and willing to share his experience with life, work and family if he thinks it will help. Not uncommon for these times, Marty has two sets of kids from two marriages, separated by about 15 years. It's given him a lot of experience parenting in a variety of contexts. Before our daughter was born, Marty talked with me frankly about the changes from coupledom to parenthood.

Marty and I both love to cook, so we decide to talk while making a meal together. We prepare brunch on a chilly May morning with a simple menu of roast asparagus, cubed red potatoes and onions, and farm-fresh fried eggs. As we dive into the work of prepping ingredients, I ask Marty about the things he remembers from his days just before becoming a parent.

"I was really unprepared for the changes that occurred," he tells me. "This baby came and was the complete central focus of everything in our life," both practically and emotionally. He explains that becoming a parent demanded a greater amount of personal growth than he had ever experienced.

I appreciate Marty's honesty about his relative cluelessness. We chuckle and season potatoes, smash garlic and add rosemary to the mix. He and his first wife moved to Vermont for the beauty of the natural landscape, and they arrived at the tail end of the back-to-the-land movement. "People weren't living in communes, but there were a lot of common beliefs. And one of them was how to parent and have kids," he says. Marty explains that part of that culture included a more equitable, less gendered parenting arrangement at home. This makes me think about my experience as a stay-at-home dad. Both my wife and I liked the idea of having a parent home with Evie, and it made sense financially and practically that it be me. For us, the arrangement hasn't felt like an attempt to buck tradition; having a stay-at-home dad is our tradition.

- Conor Stinson with daughter Evie

In the early years, Marty's work as a photographer allowed him to stay close to home, washing cloth diapers and cooking for his family. After a few years, he says he felt an

"almost hormonal need to provide." This meant leaving behind his craft of nature photography for a more traditional business: a photo lab and printing shop an hour away in Burlington. The 9-to-5 hours and commute meant a fundamental shift in the family's routine and culture, and less time at home with his daughter.

We talk about what happens in a relationship during these new life phases. I comment that transitions seem to bring the most strain to a family. As he cuts cantaloupe, Marty explains that he sees it a bit differently. Parenting is a "constantly changing dynamic," he says, rather than periods of calm followed by periods of transition.

The conversation shifts to the day-to-day work of parenting. I wonder aloud if living life like a project manager, with each detail carefully accounted for in advance, might be the best approach to fatherhood. I pull the potatoes out to stir for an even crisp and ask Marty what he thinks.

He takes a broader view. "I think role modeling is one of the most important things. Kids learn so much by watching how their parents are," he tells me. "They pick up on everything, and it really shapes their lives."

Still in the early stage of parenting, I find myself seeking answers for every problem — a kind of baby-management protocol. But here Marty suggests trying to pull back a bit from the intensity of a kid-focused life and concentrate more on my own behavior. I have to admit that being a thoughtful and self-aware parent seems more reasonable than being a "perfect" one who has all the answers and the best snacks.

As we finish frying the eggs, I ask Marty how being a "new" dad for a second time changed his parenting. "I was much more relaxed and confident, which to me meant stepping back," he says. "With first-time parents and first-time children, it's easy for me to look back and see how it's so intense. What I would wish is that parents could step back and focus on guiding their kids through life until you're ready to let them go into the world. Nature is a strong influence and, as long as I'm a good role model, things are going to work out."

My wife and I are still very much immersed in hands-on parenting. But as Evie grows up, I can see the advantages of trying to be my best self, and hoping my example guides her.

Our eggs sizzle to completion and the conversation shifts to serving bowls and getting plates on the table. We dish up the meal to Mom and Ellen, crammed around the too-small dining table we brought from Brooklyn, while Evie babbles merrily in her high chair.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.