- Kim Scafuro

In the winter, South Hero can resemble an abandoned outpost: a flat, frozen landscape dotted with burger shacks and ice cream stands, all in a state of suspended animation. But in mid-January, there were signs of life at Camp Ta-Kum-Ta, which sits tucked away on a hilltop overlooking Lake Champlain and the Adirondacks.

Inside the main lodge, a 6,000-square-foot mansion strewn with mattresses and beanbags, seven middle-schoolers — attending a winter weekend session at the camp — were trying to solve a series of clues that would allow them to open a locked storage bin. Their postures telegraphed varying degrees of enthusiasm, from somewhat engaged to supine beneath a foosball table. The boys began to drift to the edges of the room.

A casual observer probably wouldn't have noticed anything unusual in this tableau of adolescent apathy. But in the middle of a long lull, one boy turned to another and said, as matter-of-factly as he might have reported what he ate for breakfast, "I really hope my surgery ends up being on a Monday, so I can miss school."

Ta-Kum-Ta is for children and teens who, at some point, have been diagnosed with cancer. Some of the puzzle-solvers were in remission; others were undergoing treatment. But at camp, they're just kids.

"When you're here, you never hear the word 'cancer,'" said Dina Dattilio, Ta-Kum-Ta's program manager. "Here, they're just allowed to be normal and have the childhood experiences that the rest of their peers get to have."

Since 1984, Ta-Kum-Ta has offered a free, weeklong summer sleep-away camp for children with cancer who either live or receive treatment in Vermont. Campers range in age from 7 to 17, although Ta-Kum-Ta often offers spots to kids who are older or younger. In recent years, the camp's calendar of events has expanded to include three winter weekends, multiple sessions for parents and siblings, and year-round programs.

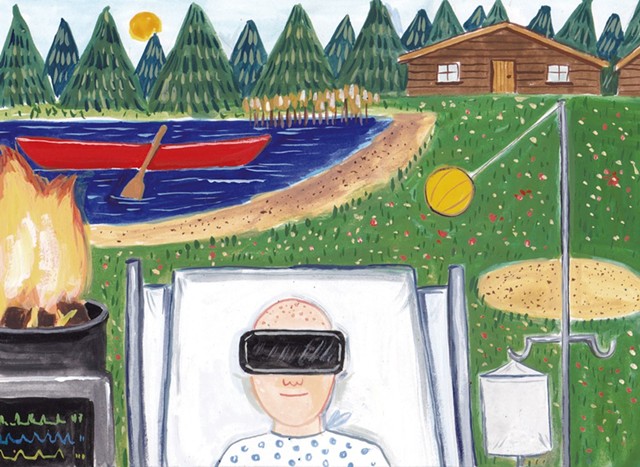

And now, with an assist from virtual reality technology, Ta-Kum-Ta also provides a 3D glimpse of camp life to kids who haven't attended before or can't go in person. In early January, the pediatric oncology team at the University of Vermont Children's Hospital began offering patients VR headsets, queued up with videos of campers swimming, ziplining and lounging in the sunshine.

The goal of the VR program, said Ta-Kum-Ta executive director Hattie Johnson, is partly to encourage new patients to sign up and partly to help them forget, even for just a moment, that they're in a hospital.

VR has become a staple at children's hospitals around the country, including at the Vermont Children's Hospital, which serves approximately 30 new pediatric oncology patients each year. At any given time, about 100 cases are in active treatment, according to Michael Carrese, senior media relations strategist at the UVM Medical Center.

"Time passes slowly when you're in a hospital," said Dr. Heather Bradeen, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at the Children's Hospital. "It's so important to keep kids as relaxed as possible and find ways to keep their spirits up on those long, difficult days."

Jennifer Dawson, a child life specialist at the hospital, said that movies and games can provide a temporary distraction from pain and procedures, but in her experience, VR has been far more effective at reducing anxiety.

"VR immerses them in a completely new environment, which is sometimes exactly what they need," Dawson said. "I can think of one kid who would always wake up from anesthesia in an incredibly agitated state, which was traumatic for both him and his parents. Then, we put VR goggles on him before a procedure, and he woke up totally calm. It was actually amazing."

Ta-Kum-Ta's VR program began with Don Bateman, a multimedia producer who lives in Williston. While riding the ferry to Plattsburgh, N.Y., one day last June, Bateman got into a conversation with a guy who told him about a summer camp in South Hero for kids with cancer. Bateman and his business partner, John Hoehl, son of the late philanthropists Cynthia and Bob Hoehl, had been interested in developing VR programs for nonprofits.To Bateman, Ta-Kum-Ta sounded like an ideal candidate for that kind of project, and Hoehl agreed to provide funding.

"I thought it would be really incredible to be able to offer the experience of a camp like that to a kid who might be too sick to attend," Bateman said.

When Johnson agreed to let Bateman film while camp was in session last August, Bateman had only heard exuberant testimonials about the transformative power of Ta-Kum-Ta. But he said that he wasn't prepared for what he called "the vibe" — the carefree, joyful attitude that seemed to permeate even the most mundane moments. During his visit, a group of kids managed to acquire thousands of tiny rubber ducks, which they dumped all over the place. One morning, at the crack of dawn, the youngest boys released four goats into the oldest girls' cabin.

But Bateman said that intertwined with the shenanigans was an ineffable feeling, simultaneously sad and uplifting. At the beginning of each summer session, the staff holds a memorial service in the Ta-Kum-Ta chapel for campers who have passed away. Johnson said the ceremony isn't about grief, but about healing.

"You just can't understand it until you've been there," said Johnson. "It's a magical place."

"Magical" is a word people often use to describe Ta-Kum-Ta. Dr. Lewis First, chief of pediatrics at the Children's Hospital, believes that going to camp can be a turning point in the treatment process.

"It can be a miraculous experience for these kids," said First. "When they come back from camp, they're dedicated to fighting, and they want to pay it forward."

First is eager to see the impact of the Ta-Kum-Ta VR program on new patients.

"For kids who aren't physically able to attend, the VR program will allow them to experience the magic. And it's going to be a great way for our younger patients to understand what a special place it is," he said.

Patients aren't the only ones who might need to be convinced of the merits of a week at camp, a proposition that can intimidate young children and provoke a knee-jerk refusal from adolescents (who, Bradeen acknowledged, tend to be the toughest sell). For parents, the decision to send their sick child away is often fraught with anxiety. Zack Engler, 27, a former camper who is now Ta-Kum-Ta's youngest board member, said that watching his mother and father worry about him was the hardest part of being sick.

The first time Engler went to Ta-Kum-Ta, he was 9 years old, and he'd only been in treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia for a few months. His mother, he said, was a nervous wreck.

"I remember my dad telling me, 'You need to write her letters like, every single day, so she knows you're OK,'" Engler recalled. "But if the VR program had been around at that point and she could have seen all the incredible experiences I'd be having, I think that the decision to let me go would have been much less stressful for her."

For Engler, Ta-Kum-Ta was life-changing. After that first summer, he returned every year until he aged out of the program, then came back as a counselor for one year while attending college at UVM. For the past seven years, he's been going back to volunteer. Ta-Kum-Ta, Engler said, has provided him with a sense of community that he's never felt anywhere else.

"When I was undergoing treatment, I was on steroids for periods of time, which made me eat a ton and put on weight," Engler said. "At camp, it was never a thing people cared about; I would be heavy one year, not so heavy the next, and it didn't matter at all." When he took off his shirt to go swimming, no one commented on the scar on his chest where his medication port had been.

"The friendships you make there are so profound," he said. "You're connecting with people on a totally different level, even if you're too young to be conscious of it, because you have this thing in common that makes you different from everyone else when you're at home."

Engler has been cancer-free for the last 15 years, but those relationships are still a huge part of his life: This summer, he's officiating the wedding of his best friend, whom he met at camp, in the Ta-Kum-Ta chapel.

If the VR program makes it possible for more people to have the experience he had, said Engler, that can only be a positive thing.

Last fall, 18-year-old Alex Blair went to the doctor for what seemed like just a cold. A few weeks later, blood tests confirmed that she had leukemia. Since September, Blair has spent all but a handful of days at the UVM Medical Center. Being away from home hasn't been easy. She misses her chocolate Lab, Taz. She misses tacos, good salads and anything that isn't hospital food. Most of all, she misses the Cambridge Fire Department, where she's been volunteering since she was 16. Whenever the ambulance from her local rescue squad passes beneath her window, they honk to say hello.

On January 15, the day she returned home for a two-week reprieve — her first break from the hospital in nearly a month — Blair and her father, Craig, became the first people to test out the Ta-Kum-Ta VR program. Even though Blair is technically too old to be a camper, Ta-Kum-Ta often makes exceptions; if she's well enough, she'll have the opportunity to attend this summer.

Blair put on the headset first. For five minutes, she sat on the bed in silence, turning her head occasionally to look at something behind her in the world of VR. She didn't say much. Every now and then, she smiled. Her father never took his eyes off her. It was a surreal moment — a girl wearing massive goggles, taking in another time and place, while the grown-ups in the room anxiously awaited her return.

When Blair removed the headset, she grinned.

"That was cool," she said.

Correction: January 31, 2019: An earlier version of this story misidentified a source of the VR program's funding.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.