- Caleb Kenna

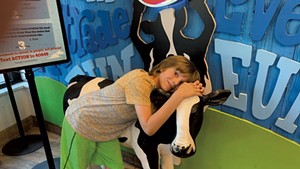

- Cousins (oldest to youngest) Ashlynn Foster, Rowdy and Remy Pope, and Allegra Ouellette visit a calf

On April 1, 1958, Harmel and Lila Ouellette bought 365 acres and 39 cows in the Addison County town of Bridport. It was the only farm they visited after they had decided to buy. "Everything looked good," Harmel recalls. "It had good buildings, good land, so we decided to make a move." At the time, he and Lila had a 1-year-old son, Steven.

The idea that, someday, his great-grandchildren would be working and playing on this land "never entered my mind," he says.

But 61 years later, Harmel, 85, is still driving tractors here on the farm that his late wife named Iroquois Acres. Now owned and operated by five of his descendants, the farm has 700 cows and more than 1,500 acres and employs eight non-family members. It's the site of a cheesemaking business run by another descendant, and it allows Harmel's great-grandchildren to make a claim that fewer than 1 percent of the people in the United States can make: They are growing up on a farm.

Once common in Vermont, and still more common here — 1.6 percent of working Vermonters are farmers compared to 0.9 percent of workers nationwide — farm life introduces kids to hard work and the subsequent pride that comes from a job well done. It instills responsibility and common sense. Kids on a farm quickly learn that life doesn't revolve around their baseball practices or social lives, but milking, chores and cutting hay when the sun shines. If it's the Fourth of July or Christmas or your birthday, you celebrate, then you do chores, though probably the other way around. Life and work are inextricably knitted together here. And when the cows get out, there's even more work to be done — or a great adventure to be had, depending on whether you're 60 or 6.

Harmel Ouellette's five great grandchildren range in age from 19 months to 19 years. They got barn boots before they could walk, and they each get a calf to start their savings accounts, like their parents did. They can sell it or breed it to start a herd; it's their choice. They've never gone to daycare. When they were tiny, they were strapped to their parents in front packs or backpacks or they hung out in strollers and wagons in the barn. Their parents, as children, spent time in baby swings and playpens in the barn, and their grandma tells a story about a cat curling up on one baby's head.

"When they say, 'brought up in the barn,' they really were," says the grandma, Harmel's daughter-in-law, Sherry Ouellette. Now, there's always a parent, aunt, uncle, grandma or cousin around to supervise the youngest children on this working landscape that doubles as a playground. The mournful moo of a cow, the staccato bleat of baby goats and the putt-putt-putt of tractors — that shifts to a higher key when they pick up speed — provide the soundtrack of their lives.

Four-year-old Remy Pope is playing in the deep, muddy tire tracks behind the dry cow/freshening barn, where cows stay when they're not milking and when they "freshen," or give birth. He balances a fat chunk of mud on his head, then lets it roll off the brim of his camo cap and splash into the water that fills the track. He giggles. And does it again.

What's it like to be a kid on a farm?

"Great," says Remy's grandpa, Steven Ouellette. "You get to do a lot of things, drive a lot of stuff that nobody else gets to, and play with a lot of stuff and have a lot of pets and a lot of freedom..."

- Caleb Kenna

When meeting the Ouellettes, a flow chart would be helpful. The family has married into two other dairy families and has members working on three different Addison County farms. But it's actually not that complicated. Steven is Harmel and Lila's only child. He and his wife, Sherry, both 62, live on the farm where Steven grew up and have three children: Nicole (Nicky), who is 42; Aaron, 41; and Stephanie, 37. Harmel lives across the road.

Nicky and her husband, Mark Foster, have two children: Ashlynn, 19, and Colin, 15, who both intend to farm. Mark and Colin work on Mark's family's farm, Foster Brothers Farm, in Middlebury. Nicky owns and operates Bridport Creamery, located here, at Iroquois Acres. Her five-year-old business buys 7 or 8 percent of the farm's milk to make cheese that is sold throughout New England. Ashlynn works at Iroquois Acres. She has an associate's degree in farm management from Vermont Technical College and will study animal science and entrepreneurship at the University of Vermont this fall.

Aaron is one of the farm's owners, along with his parents, his sister Stephanie and Stephanie's husband. Aaron's wife, Jenna, had no prior farm experience. "I was afraid of cows," she says. She works in the creamery a couple of days a week and helps with the kids.

Stephanie and her husband, Seth Pope, have two sons: Rowdy, 6, and Remy, 4. North Wind Acres, a Pope family farm in nearby Shoreham, houses part of the Ouellette family dairy herd.

Rowdy and Remy spend their days here at Iroquois Acres. Rowdy recently finished kindergarten. Every day, when the bus dropped him off after school, he flung his backpack onto the porch, put on his boots and ran to the freshening barn to see how many calves were born while he was away. One June day produced eight, all heifers. Rowdy had never been on a computer before he started school, his mom says. "They were saying, 'Oh, he's going to be behind.' I was like, If that's where he's behind, I'm fine."

- mary ann lickteig

- Remy dances in the mud

Rowdy's paternal grandmother tells a similar story about Rowdy's dad, Seth, one that Cabot Creamery Cooperative uses to promote its member farmers. "When the time came to test him for preschool, he didn't know his colors," Gail Pope says, "but he could tell you which tractor was a John Deere and which was an International. He could tell you the difference between a mower, a rake and a baler and if a cow was a Holstein or a Jersey."

Rowdy can tell when a cow is ready to give birth, and he was upset one day this spring when the family didn't heed his words, and a cow gave birth before she was moved to a maternity stall. He's the kid who flips over his toy cattle to teach the neighbor boy how to tell a bull from a cow, and he relays some eye-popping anecdotes during kindergarten share time.

"So Rowdy's teacher, when you pick them up or drop them off, if she comes and talks to you, there has been an event..." Stephanie says. "And one morning, I dropped him off, and she was waiting by the door." The weekend prior, a cow on the farm had had a prolapsed uterus. During share time, Rowdy was antsy waiting for his turn to talk, Ms. Way told Stephanie. And when he got the floor, he blurted, "My cow's uterus fell out!"

Stephanie and her brother and sister started helping on the farm when they were 6 or 7. Their children have done the same. Rowdy, already a font of farm knowledge — "All of my boy goats are cast-er-ated," he offers — has to be reined in. One of his favorite places is the freshening barn. If he sees wet spots in a birthing stall, he grabs a shovel to scrape them out, then puts down fresh sawdust, his grandma Sherry says. "We've had to correct him on that because there's some cows, that when they have babies, they just want to be left alone."

He also likes to move calves — by himself — from the freshening barn to the hutches where they are milk-fed. On this day, he guides a wobbly 12-hour-old Holstein across the mountainous, muddy tire tracks. They zigzag a bit and Ashlynn offers help: "You want me to push and you guide?" she asks. But Rowdy, with his close-cropped blond hair and sun-kissed face, wedges his tongue between his lips and muscles on. "I got it," he says.

Rowdy seems born to farm, Sherry says. "It's in his blood. He lives and breathes it ... In my house he's got his whole farm set up with gates and pastures. And when he's not out here, he's in there doing that."

Stephanie says she will not be disappointed if her two sons decide not to become dairy farmers. "For my children, I want, obviously, for them to be happy in life, but I also want them to be good people," she says. She and her siblings weren't pressured to farm, either.

"We sent them to college so they could make up their own mind, but they all came back," Sherry says. Stephanie worked as a loan officer in a bank for five or six years, but she fed calves before work and helped out after work and on weekends. Her brother, who has always wondered what it's like to have a 9-to-5 job and who laughs at the phrase "three-day weekend," marvels at another aspect of work off the farm — guaranteed income. "That's another thing that blows my mind," he says.

- Caleb Kenna

- Rowdy feeds calves

So far, the next generation is on track to farm. The oldest grandchild, Ashlynn, who spent school vacations going to sales to buy cows with her grandpa, wants to farm. "When I was getting ready to look at college, everybody — my parents, and my whole family and my grandfather — was like, 'You know you don't have to go for dairy. You're smart enough. You can do anything you want.' And I was like, 'I don't know anything else. Like, this is what I do.'"

And she likes it? "Yes," she says, without a second's pause. "I love it. It's all I know. And I love it. I love my cows."

But dairy farming isn't easy. This is the fifth straight year milk prices have remained below the cost of production. Though starting to rebound, they have dipped to 1980s prices, forcing many farmers out of business. Last year at this time, farmers were selling their milk for $14 or $15 per hundred pounds, well below the cost of production, according to Laura Ginsburg, section chief for the agriculture development division at the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets. Prices are up to about $17 now. Some farmers are making money, Ginsburg says, even though the average cost of production on a conventional Vermont dairy farm is $18 per hundredweight.

Nine percent, or 71, of the state's dairy farms closed between 2017 and 2018. Another 23 have closed this year, bringing the number of dairy farms still operating to 677, one-third fewer than the 1,015 in 2010.

Weather presents another challenge. A wet spring delayed the planting of crops, and Midwest flooding pushes up grain prices here. Still, Vermont produces 60 percent of New England's fluid milk, and dairy farming remains the dominant sector in the state's agricultural economy.

"It's definitely one of those occupations where you keep your fingers crossed and keep moving forward," Ginsburg says.

Steve and Sherry Ouellette say they managed to survive by expanding and being aggressive. "There's a lot of things that have changed, and we've had to change with them," Sherry says. They upgraded to a round baler to make moving hay more efficient; they installed a parallel milking parlor, allowing them to milk 22 cows at a time instead of one; and they added registered Brown Swiss cattle to their herd so they could sell their calves and frozen embryos. Brand new is their automatic calf feeder, which tracks each animal's intake.

The flip side of advancing the farm is sacrifice elsewhere. When Steven and Sherry's kids were growing up, they took just two family vacations. And Sherry has been waiting for a garage for her car since 1979. Whenever she thinks this might be the year, "we put up a barn," she says. They got their first air conditioner — a window unit — about six years ago. "But here our cows have got 40 fans on them," and a misting system to stay cool.

But that's how it is, Sherry says. "The cows come first. That's our living. If you don't take care of cows, you don't have a living."

She doesn't resent that. She has her family around her. She has watched her kids grow up and learn to love farming. So she will wait for her garage. "Buildings are buildings, but the part of farming I like are the memories," she says, like watching Stephanie "wheeling and dealing" to buy calves when she was in middle school and seeing how excited Rowdy gets about calves being born and how Allegra lights up playing with goats. "And smelling hay when you're cutting it," she adds. "That's what's important — and the relationships you build in the farming community.

"What do you put for a price on that?"

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.