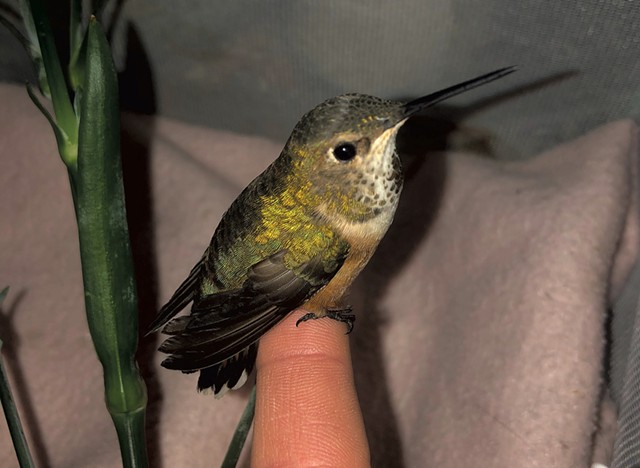

- Courtesy Of Julianna Parker

- Male rufous hummingbird rescued in December 2020

In mid-December, the nonprofit group Green Mountain Animal Defenders issued an urgent call to its supporters on Facebook seeking someone who could drive a rescued hummingbird, which was captured inside an apartment in Bennington, two hours north to a wildlife rehabilitation specialist in Addison.

First, what was a hummingbird doing in Vermont in December, when most of the flowers from which it would feed are dead? And, even if the hummingbird could be nursed back to health, where could it live?

For answers to both questions, ask Julianna Parker. She and her 22-year-old daughter, Sophia, are wildlife rehabilitators who run Otter Creek Wildlife Rescue. For the last decade, the Addison nonprofit has been accepting critters of all shapes and sizes, including possums, squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits and snowshoe hares. About the only animals Parker cannot accept are large mammals, such as moose and bears, and those that are potential rabies vectors, including raccoons, foxes, skunks and bats.

As Parker explained, in order to legally rescue migratory birds, she needed a federal wildlife rehabilitation permit, which she couldn't get without first obtaining a state permit for rehabbing small mammals.

Parker is most passionate about the feathered fliers. In a typical year, she'll rescue 100 to 150 birds. Those that survive get released back into the wild, usually with a "soft release," meaning she'll open an outside door for an hour a day and allow the birds to fly free and then return at night for safety. Eventually, they'll choose to remain outside.

December's rescued rufous hummingbird is one of more than 200 birds Parker rehabbed in 2020, which she called "an insanely busy year" for bird rescues.

Why the huge uptick? COVID-19.

With so many Vermonters now working from home and getting out in nature more often, Parker said, she's had dozens more people flocking to her with injured or lost birds.

Indeed, the list of avian species she rehabbed in 2020 span the ornithological rainbow: blue herons, blue jays, bluebirds, brown thrashers, goldfinches, green and yellow warblers, red crossbills, red-bellied woodpeckers, red-eyed vireos, red-winged blackbirds, rose-breasted grosbeaks, ruby-throated hummingbirds, white-breasted nuthatches, white-crowned sparrows, yellow-bellied sapsuckers, and yellow-billed cuckoos.

And those are just 2020's rescued species with colors in their name. The list doesn't include the chimney swifts, owls, pigeons, seagulls, starlings and wild turkeys that recently rested at Parker's roost.

Parker had no formal training in animal rescue when, at 19, she found a baby starling that had fallen out of its nest. Unsure what to do, she called a friend at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, who told her to dig up some worms and feed it every 20 minutes.

Parker did so and carried that baby starling everywhere she went for more than a month, earning a reputation as "that crazy bird lady." Later, whenever friends or family members came upon a crashed cowbird or wounded warbler, they'd bring it to her. (It helps that Parker's husband, Dale Whitlock, is a state game warden.)

She has since taught herself each species' diet, nesting habitat, migration schedule, and ideal release time and place.

- Courtesy Of Julianna Parker

- Male rufous hummingbird rescued in December 2020

Once, after rescuing three raven hatchlings, Parker noticed that the birds kept landing on the ground and walking behind her, which is unnatural behavior for ravens in the wild. The birds hadn't learned from raven parents where to land, so Parker climbed a tree to show them. The following day, the ravens began perching on tree branches.

Years after their release, Parker's ravens still come back to visit her.

"And they bring their kids," she added. "Every summer, they'll nest out a bunch of babies, and they'll teach that next generation that this is a good place to come if you're hungry or in trouble."

This year, Parker is overwintering a dozen birds, including the rufous hummingbird, five pine grosbeaks and a hairy woodpecker, the last of which, she says, "is destroying my porch at the moment."

Parker can't say why the hummingbird didn't fly south for the winter. She suspects it's a first-season bird that got separated from its family. She's found no evidence of an injury and doesn't think an older "hummer," as she calls them, would have missed its migration.

"He flies like an angel," she said. "He whizzes around the wildlife room like, well, a hummingbird!"

Her challenge, however, will be getting him through the winter in an unfamiliar environment. Hummingbirds can't be kept in conventional birdcages because their wings beat so quickly that they can break from hitting the bars of the cage. She allows this one to fly loose in an indoor aviary and wildlife room.

Food is also an issue. Because so many store-bought flowers are treated with pesticides and herbicides — and hummingbirds can't survive on low-nutrient sugar formulas alone — Parker knows of other bird rehabbers who have inadvertently poisoned rescued hummingbirds. If she can find a local flower supplier that she's 100 percent sure is chemical free, she'll give the bird daily doses of natural nectar. Otherwise, she said, she'll keep feeding him fruit flies and nectar she buys from a zookeeper organization. For now, she said, the hummingbird seems happy, healthy and well fed.

Parker's other big challenge: Because she's battling leukemia in the midst of the pandemic, she can't have volunteers at the house to help, due to her compromised immune system.

But in that regard, she said, her daughter has been a godsend. The hummingbird loves to land on Sophia's finger and drink from a dropper she holds. Sophia learned animal rehab when she was just a child, Parker noted, and is now a natural at it. In fact, Parker used to host a summer wildlife camp at which she taught kids as young as 5 how to rehab animals.

"Children have such a natural desire to help animals in need," she said. "It's so great to train their minds and their hands to do what their hearts want to do anyway."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.