In June 2012, a 3-year-old boy attending the Ed-U-Care Children’s Center, a licensed daycare provider in Essex Junction, walked off the premises and wandered across four lanes of traffic on Susie Wilson Road. Luckily, an approaching motorist spotted him in the middle of the road and pulled him out of harm’s way.

According to a subsequent investigation by the Vermont Department for Children and Families’ Child Development Division (CDD), Ed-U-Care staffers never notified authorities that the boy was missing, as is required by law whenever a child disappears from a regulated daycare program. As a state official remarked later, “Someone just didn’t count heads.”

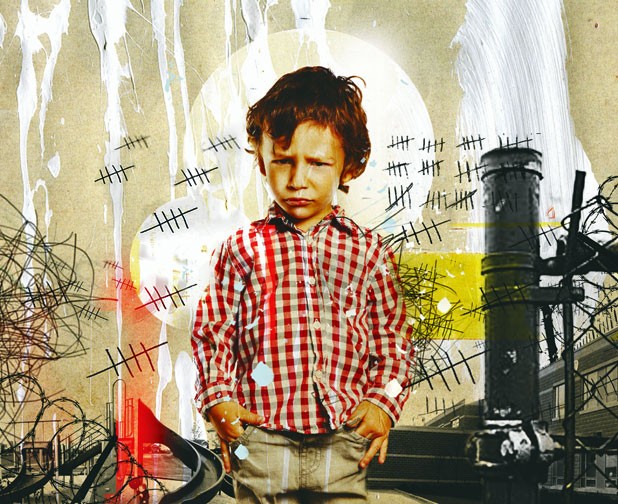

Stories like this would give working parents nightmares — that is, if they knew about them. Often, they don’t. By law, daycare centers must notify the parents of children in their care about any serious violations on the premises. But anyone else researching daycare options will find it difficult to learn about a facility’s checkered past.

Parents can look up a daycare’s regulatory history on the Bright Futures Child Care Information System — an online portal for information on all licensed and registered daycare programs. There they’ll see that Ed-U-Care was cited for 15 violations between February 2006 and June 2012.

But they won’t read an account of the June 2012 incident on Susie Wilson Road — or details of any other problems, for that matter. The write-up of the June 2012 incident reads: “Each child shall be visually supervised at all times in person by staff (except sleeping infants who are subject to in-person checks every 15 minutes) … Children must be visually supervised while napping/resting.”

Based on that assessment, a parent wouldn’t know whether a staffer merely left a toddler napping for a few minutes to change another child’s diaper — or, in this case, a child walked out the front door and into traffic. State field reports about such incidents are considered public information. But a parent has to know enough to ask for them — from either the provider or the state. It can take days, or weeks, to receive the information, by which time that daycare slot may already have been filled.

DCF officials admit they have too few people in the field inspecting daycare programs to ensure that they’re safe, clean and obeying the law. But there’s also a shortage of childcare facilities — and their numbers are actually dropping — that puts pressure on the state to keep as many places open as possible.

The problem isn’t new. In February 2012, the DCF official in charge of overseeing Vermont’s nearly 1600 regulated daycare facilities told a Senate committee that the licensing system “does not provide a reasonable threshold of safety for all children in regulated, out-of-home care.” Former CDD deputy commissioner Kim Keiser told lawmakers that the situation caused her to “lose sleep at night” because “I know we did not have the capacity to even stay abreast of situations that were directly putting children at risk.”

In retrospect, Keiser’s year-old warning was prescient.

Ed-U-Care owner Judith McKenzie describes the incident last June as “an unfortunate accident” but also an isolated one. She points out that the child was known as a “wanderer” and that the staffer responsible for his disappearance was fired.

“It was a terrible thing that happened, but it could happen to anybody,” adds McKenzie, who’s been in the daycare business for 26 years. “I’ve suffered terribly from this, as has everyone in the center.”

But the state didn’t revoke or suspend Ed-U-Care’s license. Why not?

Because the state licenser didn’t find a “pattern of neglect,” such as unsecured doors, broken fences or inadequate staff-to-child ratios, explains CDD Deputy Commissioner Reeva Murphy.

“Certainly, if we had kids walking away from the same place more than one time, we might suspend,” she adds. “Kids have walked off the premises even in five-star places … We just have to make those judgments.”

Too Few Inspectors

Officials at the CDD acknowledge that they lack the staff and funding to visit every daycare program in the state once a year, as the law requires — making it virtually impossible to observe any patterns of violations. Some facilities, especially registered home-based programs, can open for business and operate for years without a licenser ever setting foot inside to make sure it’s free of safety hazards and has operable smoke alarms, fire extinguishers and carbon monoxide detectors.

Each day, about 39,000 Vermont children, ages 6 weeks to 12 years, attend some form of regulated daycare program. The state has just seven licensing field specialists to oversee and inspect 1577 regulated programs statewide. That’s a caseload of 225 programs per licenser — the highest ratio of any state in the country.

The situation could change this year. The state’s budget for fiscal year 2013 includes funding to hire two more licensing field specialists, which would bring CDD’s total to nine and reduce the average caseload per licenser to 178 programs. But Murphy says she’d need a total of four more licensers to be able to visit every program in the state at least once a year.

Licensed programs, which are larger and have stricter rules than registered in-home daycare programs, are far more likely to be inspected. Currently, 90 percent of all licensed centers are inspected annually, but only 47 percent of home-based programs are.

Elizabeth Meyer is executive director of Child Care Resource in Williston, a nonprofit that helps connect parents with daycare providers. Last year she told the Senate Committee on Appropriations that, all too often, her staffers are “the only professionals who lay eyes on a Chittenden County program in a given year.” According to her own statistics, in the previous year, licensers visited just 55 percent of all regulated programs in Chittenden County. One program had gone more than five years without an inspection; 14 percent — or 44 programs — had no recorded state visits at all.

One Colchester daycare went without a license for almost a year — and essentially had its record of violations expunged — because of what the owner called a “miscommunication” with the state. The license for Muddy Hands Enrichment Center expired in April 2012 and was not renewed. State officials assumed the daycare had closed and removed it from the Bright Futures database.

The facility didn’t show up again until this reporter asked about it. Shortly thereafter, the state’s database indicated that a new license had been issued on December 30, 2012. However, 11 prior regulatory violations — from minor things such as missing job references to more serious ones, including the absence of staff trained in infant CPR — had been wiped clean from its record. Why? Because the new license was issued to different owners under a slightly modified name: Muddy Hands Preschool & Child Center. One of the new owners of Muddy Hands, Naomi Salls, says the state never received license-renewal paperwork from the previous owner.

“I had a little talk with my staff about that one, making sure our i’s are dotted and our t’s are crossed,” says Murphy, “because that’s a huge liability issue.”

There were no resulting regulatory ramifications for the center, which operated without a license for almost a year.

By law, Child Care Resource and its counterparts around Vermont are prohibited from telling parents about problem daycares even when they are aware of them; they can only make referrals, not recommendations. Lee Lauber of the Family Center of Washington County says her staff is sometimes conflicted about what it can and cannot reveal to parents. As long as DCF has granted a program the legal right to operate, she says, it’s considered “an interference” to share information with prospective parents that might paint the daycare in an unflattering light.

Lauber calls it “a very interesting conundrum.”

“There have been times when many concerns have been raised and some of them have been addressed and others still remain, and the program stays open,” she says. “That can go on for years.”

Not a Pretty Picture

In some instances, the state has allowed daycare centers to remain open despite violations so egregious they put kids at risk of serious physical or emotional harm. Feels Like Home Playschool, a licensed daycare center in Essex Junction, racked up 16 violations in 2012, several of which were serious enough to warrant mandatory notification letters home to families.

Here’s what the Bright Futures database says about the rules broken: “Derogatory or humiliating remarks made by staff in presence of children or families are prohibited”; “Infants shall be held during bottle feedings unless they are able to hold their own bottle and wish to do so”; and “No employee, volunteer or parent shall use any form of inappropriate discipline or corporal punishment.”

The state licenser’s seven-page field report, dated November 6, 2012, paints a far more disturbing picture of the care Feels Like Home provided. That report indicates that a staffer “grabbed and squeezed a child’s face with one hand, followed by pushing the child away because the child walked into a puddle.”

Another entry indicates that, “staff frequently yell[s] at children in an abrupt, harsh tone on an almost daily basis. A staff member was observed yelling at a crying child while face-to-face with this child.” That same staffer was later seen “changing to a positive, friendly tone upon a parent’s arrival.” Still another employee was overheard telling a child, “If you hurt that baby, I swear to God you’re gonna sit outside until your mom gets here!”

According to the report, the “derogatory or humiliating remarks” included “staff call[ing] children names such as hog, retard, moron, idiot, stupid and momma’s boy.”

Other entries in the report suggest that physical and emotional abuse occurred, such as “staff engage[s] in threatening behavior that is frightening for children.” In one instance, a teacher “motioned quickly toward the child’s head with the back of her hand as if to hit the child, followed by kissing the child on the head.”

The licenser further documented that “one teacher held a preschool-age child by the ankles, swinging the child like a bat at a dodge ball thrown at the child by a second teacher … hitting the child in the chest area several times. The child’s arms flailed and the child appeared to be upset.”

The licenser also observed potentially life-threatening bottle-feeding practices. In one case, an infant was observed sleeping in a portable crib with a “boppy pillow placed under the infant’s head, with a blanket wrapped around the sides to hold the bottle in the infant’s mouth.”

The licenser immediately notified the facility’s managers and staff that such practices put infants at risk of choking, as well as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The managers’ response? According to the report, she stated that her staff has been “repeatedly” warned not to do this, but that supervisors “don’t know what else to do when staff do not follow directions.”

The report also indicates that information provided to licensers on five previous site visits was determined to be “false and designed to impede and deter CDD investigations.” In other words, the operators of Feels Like Home evidently knew that what they were doing was wrong — if not dangerous and illegal — but did it anyway, then tried to cover it up.

Were it not for independent video footage provided to investigators — footage which the state now says is no longer available, in response to a reporter’s records request — many of the more dramatic violations documented by the licenser might have gone undetected and unaddressed.

Nonetheless, Feels Like Home Playschool continues to operate.

“No corporal punishment was observed,” says Murphy by way of explaining the decision. Staff behavior “was what we considered inappropriate guidance behavior.” She says the licenser spent four days at the facility afterward, which she calls “a long time” — a typical visit lasts a few hours. The owners notified parents and made staff changes, and regulators increased their surveillance with repeated follow-up visits.

“[Our staff] had this huge discussion at the time that kids should not be subjected to this every day, that these people are just mean. And I agreed with them 100 percent,” Murphy says. “But again, if I’m going to shut this place down because these people are unpleasant, do I have a valid [reason]?”

A spokesperson for Feels Like Home, who agreed to talk to a reporter on condition of anonymity, claims that many of the findings in the state’s report were untrue. She says the allegations about derogatory and humiliating language were actually uttered by parents, not staff. She admits that a child was once held by his feet but claims the child “giggled.” She denies that a dodge ball was ever thrown at the child.

The only allegation she admitted to was the most serious one: that a child was left sleeping in a crib with a bottle propped in his mouth.

“Yeah, we deserved that,” the spokesperson admits. “It was wrong of them to do it, because we always told them not to.” However, she claims there was always a staff person nearby.

But such denials run contrary to what several former clients say about Feels Like Home. Six parents whose children attended the Essex Junction daycare pulled their kids out prior to the state’s visit in November. All say the state’s report is consistent with their own children’s experiences there.

One mom, who declined to be identified, says her daughter attended Feels Like Home for about five months. She says the girl, who has a speech impediment, often came home crying and complained that the staff made fun of her because of the way she talked.

Another mom, Teeshia Farmer of Essex, claims she once arrived to pick up her 9-month-old son “on a cold, 40-degree fall day” and found him outside in an Exer-Saucer, soaking wet and crying. She says she never went back. As she puts it, “I refused to pay for my son being neglected.”

Melissa Barrows of Westford says she once found a “handprint” on her child’s arm that clearly showed “three fingers and a ring.” She says a staffer admitted to having restrained the child but downplayed the injury by saying that some kids bruise easily. Barrows says her child also came home complaining that the daycare people were being mean to her and called her names.

“I couldn’t get my child out of there fast enough,” Barrows says. “I can’t believe this place is still open.”

Feels Like Home currently cares for about 20 children, with openings for an additional dozen. By law, Child Care Resource, the designated childcare resource agency for Chittenden County, must refer parents there unless the center is subject to an active investigation.

Supply and Demand

Regulators “walk a fine line” between protecting children and maintaining an adequate supply of providers to meet the demands of working families, according to Murphy.

“Our most important responsibility is to protect the health and safety and well-being of kids in the program. That’s number one,” she says. “But, number two, we also want to build a vibrant system so that when parents are looking, they have good choices to make. So we want to increase supply. We don’t want to just be shutting people down.”

License revocations, she adds, happen “very rarely — maybe only four or five times a year in center-based programs.”

In fact, CDD revoked only two daycare licenses in 2012. In the first case, a registered in-home daycare provider, whom Murphy declined to identify, had its registration suspended because an adolescent living in the house was a “prohibited person” — that is, someone with a criminal record involving violence, assault or sexual misconduct. Murphy says state authorities entered the home, immediately notified all the client families and waited on-site until the last child was picked up.

In the second case, the state revoked the license of the Village Play Station in Pittsford for its “spotty compliance history,” incomplete documentation and “false information” provided to licensers — not for any health or safety violations. But Village Play Station appealed its suspension and has been allowed to remain open until that is resolved.

As of press time, the Bright Futures database showed no listing for Village Play Station, which means its regulatory history is invisible to the public. A phone call confirmed that the center is still accepting new clients.

In a third case, the state persuaded an in-home daycare provider in St. Albans to voluntarily surrender her registration after inspectors found “way too many kids” for the number of adults on site — 17 children for one adult, including six children under the age of 2. By law, a registered in-home provider cannot have more than two infants.

“License revocations tend to be messy,” Murphy says. “Sometimes it’s much better for us, and more timely for parents and kids, if the provider voluntarily goes out of business.”

When they don’t, she says, mandatory parental-notification letters “allow the parents to say, ‘Wow! That’s the last straw for me!’ And then the market takes care of the problem, because you can’t stay open for long if your parents are leaving.”

Murphy says her agency prefers to work with daycare providers to improve their practices rather than shutting them down. As Lauber points out, when a program closes, voluntarily or otherwise, it causes tremendous disruption, especially in more rural areas of the state. As she puts it, “If 30 to 50 kids suddenly need a place to go by the following Monday morning, the system cannot absorb it easily.”

Change on the Way?

If the childcare situation appears dire, relief may be in sight. Vermont is in the midst of a comprehensive review and overhaul of its rules and regulations governing daycare programs. Last year, the state hired an outside contractor, the National Association for Regulatory Administration, to go through its current procedures and recommend best practices based on what other states are doing. For the last nine months, those rules have been under discussion with a diverse group of stakeholders, including daycare providers.

According to Murphy, the newly proposed rules will be made public and presented to the legislature in the next few months. The public will then have an opportunity to weigh in and offer comments and suggestions on how they could be further improved.

In the meantime, child-welfare experts urge parents to ask potential childcare providers plenty of questions, such as: “Are you registered with or licensed by the state of Vermont?” “Have you ever had any documented complaints by the state?” and “If so, what were the problems and how did you correct them?”

Parents can also turn to their community childcare-support agencies, which can help parents identify providers, look up their regulatory track records and explain other ways of measuring quality.

One such method is with DCF’s voluntary rating system called STARS — STep Ahead Recognition System — for childcare, preschool and after-school programs. Providers who choose to participate in STARS have shown a willingness to go above and beyond the state’s minimum requirements. The one- to five-star rating system provides parents with one way to gauge programs and the qualifications of their staff.

But even the STARS system isn’t perfect. After all it’s been through, Ed-U-Care still maintains a three-star ranking.

A version of this story first appeared in the February issue of Kids VT, Seven Days’ free monthly parenting publication.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.