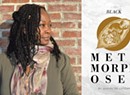

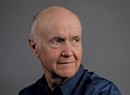

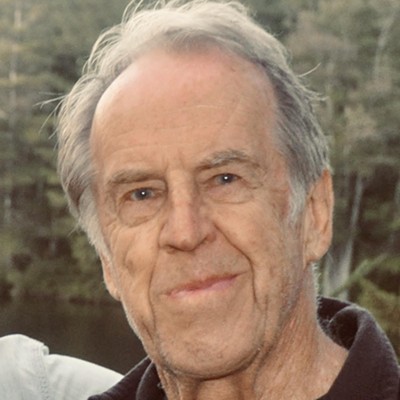

- Courtesy of Katherine Wolkoff/Steven Barclay Agency

- Louise Glück

From a young age, Louise Glück (April 22, 1943-October 13, 2023 ) aspired to be a great poet — but not in the sense of becoming a household name during her lifetime, which she viewed, with characteristic asperity, as a form of failure. "When I'm told I have a large readership, I think, Oh great, I'm going to turn out to be Longfellow," she said in a 2009 interview. "Someone easy to understand, easy to like, the kind of diluted experience available to many." Glück's ambitions were longitudinal: She wanted to write for the ages.

Glück, who lived and wrote for many years in central Vermont, pursued this calling single-mindedly, often at a profound psychic cost. Over six decades, she wrote more than a dozen books of poetry, prose and criticism and, as it happened, won almost every major honor available to a poet on this earth, including the Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award and, in 2020, the Nobel Prize in Literature. She died of cancer in Cambridge, Mass., on October 13, at the age of 80.

Glück frequently used her own life as source material, rendering autobiographical facts with dispassionate precision. Her poems are at once accessible and remote, marked by plain diction, jarring directness and a vague sense of foreboding. The words "austere," "bleak" and "oracular" have all cropped up in reviews of her work over the years, but she could also be wickedly funny. "I had a dream: my mother fell out of a tree. / After she fell, the tree died: / it had outlived its function," she wrote in "Fugue," a poem from her 2006 book Averno. Greek mythology often figures prominently in Glück's work, but she was mainly interested in bringing the gods down to earth. "Persephone is having sex in hell," reads another verse from the same book.

She didn't find transcendence in high places; for Glück, the sublime was something that filtered in through the cracks of everyday existence. Even then, it was usually suspect. "Only a poet susceptible to authentic rapture makes an art out of hunting down its counterfeit," Dan Chiasson wrote in a 2012 New Yorker review of her collected works.

Glück served as Vermont's poet laureate from 1994 to 1998 and as United States poet laureate from 2003 to 2004, duties she fulfilled with no great enthusiasm. "She didn't like the demands of having a mass of people to relate to," said Chiasson, a poet and a professor at Wellesley College, who met Glück in Cambridge in the late '90s. "Whether it was a poem or a dinner, she wanted it to be intimate, one-on-one, and she had that relationship with perhaps dozens at any given moment, over the years hundreds. We all felt singled out."

On and off the page, Glück was uncompromising in her sensibilities. She was so religious in her preference for emotionally intense dialogue with just one person at a time that many of her closest confidants never met each other.

She didn't drive, due to epilepsy, and often mentored younger poets in exchange for help with errands. Chiasson used to bring Glück meat from her favorite gourmet butcher in Boston in return for feedback on his poems. This arrangement came to a sudden end, he said, when he failed to check the weight of a game hen, as Glück had instructed him, and arrived at her door with an obese bird.

For most of the past two decades, Glück divided her time between Cambridge and Berkeley, Calif., while teaching poetry at Yale and Stanford universities, but she never lost her deep sense of connection to Vermont. "The place was always a solace, no matter how difficult my life was at a particular period, or how flourishing," she told the Nation in 2022. "I felt that it took care of me in some way, was seeing to me."

After she won the Nobel, she used some of her $1 million prize money to buy a house in Montpelier across the street from one of her closest friends, novelist Kathryn Davis. When Glück learned she had cancer, in early October, she and Davis thought they would have at least a year in which to process her dying together. As it turned out, they had less than two weeks. Glück died at her home in Cambridge one day before Davis had planned to visit her.

- Courtesy Of Henri Cole

- Louise Glück (left) receiving the Nobel Prize in the backyard of her home in Cambridge, Mass.

"Louise was not the kind of person who ever stayed somewhere she didn't want to be," Davis said. "I think she knew that whatever was going on, if she hung around, was not going to be great. She really did just leave the room."

Glück was born in New York City in 1943 and grew up on Long Island. Her father, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant son with unfulfilled literary ambitions, cofounded the company that invented the X-Acto knife, a metaphor so on the nose that Glück herself would have rejected it. Her mother, a homemaker, had studied French at Wellesley. As children, Glück and her younger sister, Tereze, sought their mother's approval — which, in Glück's eyes, was rarely bestowed.

As a teenager, Glück became severely anorexic. Her rejection of food, as she wrote in an essay, "Education of the Poet," was both an assertion of independence from her mother and a primal scream for her attention: "Like most people hungry for praise and ashamed of that, of any hunger, I alternated between contempt for the world that judged me and lacerating self-hatred."

Too frail to attend college, Glück spent seven years in psychoanalysis while taking poetry workshops at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University, where she studied with Léonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz. She published her debut collection, Firstborn, in 1968, at the age of 25. Her early work bears little resemblance to what she produced soon afterward, mostly because it sounds more like Sylvia Plath or Anne Sexton than Louise Glück ("O innocence, your bathinet / Is clogged with gossip"), but she was already zeroing in on her big themes — family, desire and its humiliations, the alienation of the body from the mind.

Following a brief marriage to Charles Hertz Jr. and a demoralizing bout of writer's block, Glück accepted an invitation to teach at Goddard College in Plainfield, in 1971. Around this time, Davis, then a student at Goddard, met Glück for the first time at a poetry colloquium.

"Very early on in our conversation, I was telling Louise how miserable I was in my first marriage, how I thought I would just leave and move to the Hebrides Islands, where I thought I'd like to live for some reason. I felt comfortable telling her all of this," Davis said. "Anything generalized did not interest her. But the particulars of you, your life — she was very interested. And she really listened."

To Glück's surprise, she loved teaching at Goddard, and poems began coming to her again. "I feel better, feel closer to myself, than I have in years," she wrote in a letter to her parents in fall 1971.

Her notebooks from this period, housed at Yale's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, document the familiar anxieties that roiled beneath this newfound happiness. Between winter 1972 and spring 1973, she existed in comorbid states of self-doubt ("It is so hard for me to work up some belief in what I do"); obsessive guilt ("General worry pertaining to weight and poetry, a terror of misplaced abundance"); general malaise ("I do not enjoy writing"); and an almost Calvinist sense of predestination ("[Mark] Strand said, 'No one is great anymore; you and I, if we're lucky, will be of the thousands.' I stubbornly reject that judgment").

"When you first start out as a young poet, you think you're going to set the world on fire," said Glück's longtime friend and fellow Vermont poet Ellen Bryant Voigt, who met Glück soon after she arrived at Goddard. "But she knew it. She felt called to it."

In 1972, Glück met Keith Monley, a carpenter who was working on Voigt's house in Cabot. "The first complete sentence I can remember Louise addressing to me was 'My, what wonderful genes you must have,'" Monley recalled. Less than a year later, they had a son, Noah. When Noah was a toddler, Glück and Monley broke up. (Noah, now a sommelier in San Francisco, declined to be interviewed; Monley, who lives in South Hero, reconnected with him and Glück in the mid-'90s and remained a close friend of Glück's until her death.)

In 1977, Glück married John Dranow, who founded the summer writing program at Goddard. Over the next two decades, she published the works that would establish her reputation as a major American poet: Descending Figure (1980), The Triumph of Achilles (1985), Ararat (1990) and The Wild Iris (1992).

By the early '90s, Glück's relationship with Dranow was unraveling. Her 1996 book Meadowlands refracts the end of their marriage through The Odyssey — the husband cast as a philandering Odysseus, the wife a bitter, though surely not blameless, Penelope. The poems in Meadowlands are often ruthlessly funny, featuring a husband and wife who lob little grenades back and forth. "I said you could snuggle," she writes in "Anniversary," in the voice of the husband. "That doesn't mean / your cold feet all over my dick."

Another couple, the Lights, appear throughout the book as a foil to Glück's faltering union. "I wish we went on walks / like Steven and Kathy; then / we'd be happy," Glück writes in "Meadowlands I." "You can even see it / in the dog."

In real life, Steven and Kathy Light lived next door to Glück and Dranow in the village center of Plainfield. Their houses were close enough that the Lights could hear opera music wafting from Glück's open windows in the summer, and Glück could hear the Lights practicing in the evenings with their klezmer band. Steven would often see Glück standing motionless in her yard, staring into the distance.

"I always thought, She looks really involved in something. She must be thinking about her poems," he said. Occasionally, he would see her drying the salad greens she grew in her garden by whipping them around violently in a mesh bag attached to a string.

By all accounts, Glück was a brilliant cook, having sublimated her need to control food through anorexia into mastery of another art. The recipes she invented, still beloved by many of her friends, were usually quite labor intensive. Around Christmas, according to Voigt, Glück was fond of making a mousse that involved roasting large quantities of chestnuts, then peeling them until her hands were raw.

- Courtesy Of Henri Cole

- Glück in her garden in Cambridge, Mass.

Along with Voigt and her husband, Fran, Glück and Dranow founded the New England Culinary Institute in 1980, which operated in downtown Montpelier for 40 years before closing in 2020, due to long-standing financial troubles. When Glück and Dranow divorced, their business relationship also imploded, and Dranow left the school's board of directors in 1998. He died in 2019.

After Glück moved to Cambridge, in 1998, she entered the most prolific period of her career, publishing four books in a little more than a decade. She also continued to teach — at Williams College, Stanford and Yale. If she was a maternal figure to her students, she played the role as her own mother had: disabused of sentimentality, with an uncanny ability to cut to the quick.

"You would give your heart up, and it would be weighed," said Noah Warren, who studied with her at Yale and Stanford. "Her voice was so inevitable, and her judgments were so hard to ignore. The seriousness of that attention — to feel read with such scarifying intensity — is so rare." The force of Glück's appraisal, Warren said, was "the defining experience of my education." To sustain her interest was to feel chosen.

For all her insistence upon being in control in virtually every other part of her life, Glück relished being a passenger. In March 2022, she and one of her friends, the poet Henri Cole, took a road trip from San Francisco to Claremont, Calif. She brought along a picnic and a few opera CDs, to which she sang along without inhibition. "I was so surprised to see that part of her," Cole said. "It was this totally relaxed, girlish side." This may have been a small but genuine regression. In "Children Coming Home From School," from her 1990 book Ararat, Glück inhabits the perspective of a girl longing for an irretrievable state of dependence, which manifests as jealousy of her younger sister in her stroller: "I walked very slowly, to appear to need nothing. / That's why my sister envied me — she didn't know you could lie with your face, your body / ...She wanted freedom. Whereas I continued, in pathetic ways, / to covet the stroller. Meaning / all my life."

Glück often found herself incapable of writing. Her silences sometimes lasted months and even years, agonizing periods in which she feared she would never write again. As Glück said in a 2014 interview with Poets & Writers, "When I'm not writing, all the old work becomes a reprimand: Look what you could do once, you pathetic slug."

When Glück was writing, she tended to work feverishly. "The silences were her listening for a new voice, a new pattern," Cole said. "When it comes, you want to record as much of it as you can before it ceases." The poems in The Wild Iris, which won the 1993 Pulitzer Prize, emerged in a spasm of fluency over just a few weeks, following two years in which Glück wrote little and read nothing but garden catalogs.

Partly out of superstition, partly out of her reflexive distrust of mainstream popularity, Glück had a habit of turning against her most acclaimed and anthologized works. She craved validation, but she was often skeptical of it when it came. "It made me really nervous to praise her," Chiasson said. "What she wanted was accurate analysis. What she wanted was to be understood."

When Glück found out she had cancer, according to Davis, she absorbed the news with surprising equanimity. "I've had a good life," she told several friends in an email. In her Nobel Prize lecture, which she delivered five months before she died, Glück talked about a particular verse in William Shakespeare's Cymbeline that she had loved as a young girl, "understanding probably not a word but hearing the tone, the cadences, the ringing imperatives, thrilling to a very timid, fearful child: 'And renownèd be thy grave,'" she said. "I hoped so."

In the spring, Glück will be buried in Montpelier's Green Mount Cemetery, in Davis' family plot. A bench inscribed with the verse from Cymbeline — "Quiet consummation have; / And renownèd be thy grave" — will honor her memory.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.