A bold and affecting show at the Vermont Folklife Center pairs 35-year-old photos of African American prisoners in New York with contemporary audio narratives by young Vermonters returning to society after serving time.

Visitors to the Middlebury gallery are given headsets to listen to an hour’s worth of excerpts from interviews conducted at Return House in Barre by East Calais-based audio producer Erica Heilman. But the main attraction is a series of portraits shot by Neil Rappaport in the early 1970s at a maximum-security prison in Comstock, N.Y.

It’s better to experience the words and images separately, despite curator Gary Sharrow’s claim on a text panel that “the experiences of both groups of men are in some ways remarkably similar.” The audiotape and the photos both warrant full attention; besides, as Sharrow also states, “These are markedly different populations from different eras and different locations.”

Rappaport, who died in 1998, taught photography to inmates of the Comstock facility, which was fewer than 10 miles from his home in Pawlet, Vt. He had volunteered to share his skills immediately following the 1971 uprising at Attica prison in upstate New York. That four-day revolt ended in a bloodbath that took the lives of 33 prisoners and 10 of the hostages they had seized.

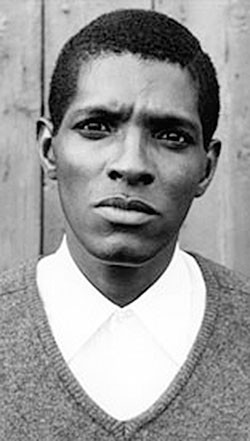

During his three years at Comstock, Rappaport made more than 300 black-and-white portraits, about 30 of which are on view at the Folklife Center. Most were shot against a plain background because the authorities would not permit photographs of the prison’s interior. The show does include a few distant views of the penitentiary shrouded in clouds and ringed by barren ground, looking like a dungeon in a Hitchcock movie.

Rappaport’s almost exclusively African American subjects strike a variety of tough and tender poses. Shirtless musclemen glower erotically in some of the shots, while in others Nation of Islam members wearing their trademark bowties stand stiffly in military formation. There are also smiling saxophone players, two jailhouse artists showing off their paintings, and an inmate who cups a pair of pet pigeons in his hands.

Susanne Rappaport, who has maintained her late husband’s portfolio, aptly describes the Comstock photos as theatrical and expressive. These portraits, she adds in a text panel, can be read as “a form of resistance,” with the prisoners appearing “free for the moment.”

In Heilman’s tapes, half a dozen young Vermonters offer matter-of-fact accounts of reckless and sometimes violent behavior. Like the photos, they’re alternately touching, funny and frightening.

One of the men interviewed at the Barre halfway house tells of his transformation in jail from “little bitch” to big bully. Upon his arrival, the ex-inmate recalls, “Everybody in that jail tested me. They’d take my stuff. I was coming off heroin at the time and was really sick.”

He came to act on the understanding that in jail it’s beat or be beaten. “Progressively,” he says, “I fucked everyone up. Everybody respected me.”

The same speaker adds in a later excerpt that he occasionally misses the predictability of life behind bars. “It’s nowhere near as hard as being out here,” he says.

Another of Heilman’s sources tells her he wears a tattoo of his mother’s name. “She’s the only woman on my body,” he says. “I love her.”

The man’s mother came to visit him once a few weeks before his release. “She was drunk,” he relates, then quickly adds, “It’s the thought that counts.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.