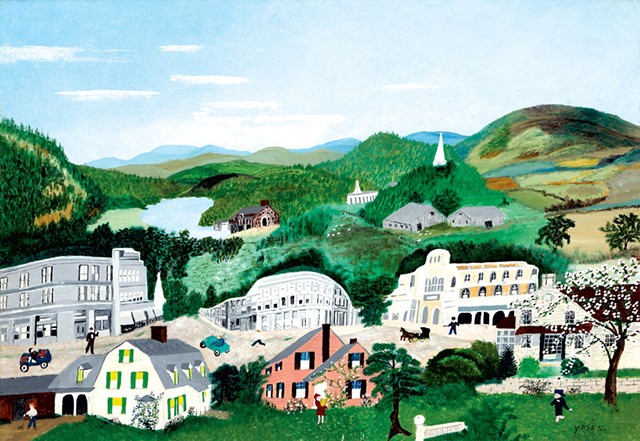

- Courtesy of Shelburne Museum/Bennington Museum

- "Bennington, 1945" by Anna Mary Robertson "Grandma" Moses.

One of southern California's most iconic art destinations is Salvation Mountain, a singular work permanently installed outside the small desert town of Niland. Some 50 feet high, the "mountain" is made of adobe and candy-colored paint and emblazoned with, among other things, the simple declaration "GOD IS LOVE." This is the life's work of the late Leonard Knight, a Vermonter who grew up in Shelburne Falls.

Having made his way across the U.S., Knight channeled his religious fervor into the monument, tirelessly adding to the exuberant creation until his death two years ago at age 82. Knight was widely recognized, and beloved, as a so-called "outsider" artist.

Salvation Mountain is splendid, but Vermonters don't need to cross the country to see brilliant examples of "outsider," or self-taught, art — or to participate in debates about its various definitions. Three concurrent summer exhibitions in the Burlington area provide provocative and diverse access points: "Grandma Moses: American Modern" at the Shelburne Museum, through October 30; "Amazing GRACE" at the Amy E. Tarrant Gallery, through September 3; and "Exaltations: Grassroots & Vernacular Art" at New City Galerie, through July 26.

As Bennington Museum curator Jamie Franklin put it, "It's rare you can go to a city the size of Burlington and see three world-class exhibitions of self-taught and folk artists."

Long associated with idealized rural life, Vermont is a particularly fruitful place from which to consider the booming popularity of self-taught art. The genre is inextricably linked to ideas of physical, cultural and psychological isolation, as well as of "authenticity." Another descriptor frequently used for this work, "grassroots," likewise resonates in Vermont's environmental and political arenas.

While the timing of these exhibitions may be coincidental, examining them together reveals that tiny Vermont has strong connections to this nebulous — but increasingly visible — corner of the art world. The exhibits may also challenge how art making itself is defined.

Was Grandma Moses a Modernist?

Anna Mary Robertson Moses, aka "Grandma Moses," is considered one of America's most popular artists of the last century. Though she lived and worked in Eagle Bridge, N.Y. — about 15 miles west of Bennington — Moses maintained strong connections during her life with both the Shelburne and Bennington museums. The latter is home to the largest public collection of Moses' works, and Shelburne director Tom Denenberg asserts that most people think of her as a Vermont artist.

Moses painted cheerful rural landscapes and depictions of activities such as sleigh riding, quilting bees and social gatherings. New York art collector Louis J. Caldor "discovered" Moses in 1938 when he found and purchased some of her paintings in a Hoosick Falls shop during a trip upstate.

"Grandma Moses: American Modern" is groundbreaking for bucking the paradigms that have historically defined the artist's career — namely, she is typically seen as either a singular icon of American folk art or an over-popularized stereotype. Organized collaboratively by the Shelburne and Bennington museums and curated by Denenberg and Franklin, this exhibition boldly suggests that Moses and her work exist within the modernist tradition that was taking shape during her career.

"Our goal from the beginning," Franklin said, "was to help people understand that Moses wasn't this random phenomenon."

During a recent gallery visit, Denenberg commented that folk art is "an invented art historical category" that emerged from the Depression to fill a need for identifying "what is native, good, right." At that time, he said, many saw it as epitomized by the "northern New England small-town democracy" that Moses pictured.

The show includes dozens of Moses paintings, along with ephemera such as mass-produced housewares and textiles bearing her designs. Viewers can also see landscapes by her contemporaries, such as Scottish American genre painter James Hope, and by fellow self-taught artists Joseph Pickett of Pennsylvania and Polish-born Morris Hirshfield.

While Moses did paint idyllic country scenes, exhibition text and catalog essays make clear that she did not merely paint what she saw around her. For example, in "The Battle of Bennington," Moses included the Bennington Batttle Monument, which was built more than a century after that 1777 conflict. With its bright greenery and wayward perspective, the painting renders the violence of war as an innocent product of her imagination.

The exhibition describes Moses' stash of "art secrets" as an important source of inspiration. Her collection of clipped popular imagery included an ample selection of inexpensive Currier & Ives prints, which appealed to the American public of her era. Several of these prints are on view, including "Home to Thanksgiving," in which a family is seen performing various activities at their country homestead.

Moses' gleaning and borrowing pave the way for the exhibition's presentation of works by artists Joseph Cornell, Miriam Schapiro and even Andy Warhol. The juxtaposition encourages us to draw parallels between Moses and these artists' decidedly "contemporary" practices of assemblage and artistic appropriation; it was, after all, with bald-faced appropriation and practices of mass production that Warhol made his name.

Like Moses, Cornell was self-taught, yet his box assemblages have moved through history free of the restraints accompanying the label "folk art." For example, WikiArt categorizes Cornell's shadow box "Cassiopeia 1," which is on view at the Shelburne, as "surrealism."

Schapiro, who died last year, was a Toronto-born feminist-art pioneer. In the 1970s, she introduced the concept of "femmage" in an essay considering women's practices of combining disparate elements into unified assemblages such as quilts and scrapbooks. Her work "Patience" at the Shelburne Museum features a delicate white apron laid over a quilted textile background. By including it, the curators suggest that Schapiro's piece is in dialogue not only with Moses' use of collage but with the apron that constituted the latter's uniform of sorts, which is also on view.

While the exhibition works to blur the lines between "traditional folk" art and modernism, new interpretations of Moses also attempt to illuminate her links to grassroots art. Franklin joined the Bennington Museum in 2005 and has since spearheaded efforts to grow and strengthen the institution's collection of contemporary self-taught works. Aside from his professed personal passion for the genre, he aims to keep the museum's main draw — Moses — relevant and dynamic.

"Seeking to provide a broader context for understanding Moses' creative output, the museum recently began to actively collect the work of modern and contemporary self-taught artists with ties to the region," Franklin wrote in a fall 2015 essay for Antiques & Fine Art magazine. Such artists include the late Gayleen Aiken of Barre; Larry Bissonnette and the late Paul Humphrey, both of Burlington; and embroidery artist Ray Materson, who lived in Vermont from 2009 to 2011.

The most prominent public milestone of this ongoing initiative was perhaps Bennington's 2015 exhibition "Inward Adorings of the Mind: Grassroots Art From the Bennington Museum and Blasdel/Koch Collection." On view July through November last year, the show emerged from Franklin's collaboration with married Burlington collectors Gregg Blasdel and Jennifer Koch.

'In Another Realm'

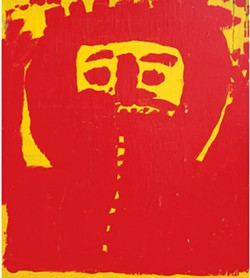

- "Untitled" by Mary T. Smith

"Exaltations: Grassroots & Vernacular Art" at New City Galerie features works from Koch and Blasdel's collection, along with those of William L. Ellis and Julie Coffey. The show presents a strong core of southern, African American self-taught artists. A selection of 10 untitled works by the late Memphis artist Hawkins Bolden lines two walls of the gallery. Each is labeled "Scarecrow." Yet, while they're made from humble materials, these objects are in no other way like a typical scarecrow.

Bolden's totem-like constructions are made from scrap metal and other detritus, including tin cans, a hubcap, a cookie sheet and slices of hosing. Rough-edged holes puncture the metal at seemingly random intervals. Decidedly abstract, the works are "anthropomorphic in name only," as collector Ellis puts it. Bolden, who was blinded after a childhood traumatic brain injury, initially began creating the works as yard sculptures meant to keep away birds.

Also on exhibit are Jesse "Outlaw" Howard, Mary T. Smith, Rev. George Kornegay and Ed Root, as well as works by Vermont artists Christy Clapper and James Patterson.

What all of these artists have in common is their designation as grassroots artists — a term coined by Blasdel in a 1968 Art in America essay. In the words of the "Exaltations" curators' statement, "The work of the Grassroots artist is unfettered, ignores current fashions, and rarely draws from the traditions of Western art history."

As the show's title suggests, many of these works have a religious undercurrent, in keeping with outsider art's frequent association with otherworldly or spiritual directives. Three abstract portraits by Kornegay are titled "Black Jesus," "Jesus" and "Moses." Kornegay was an Alabama minister who grew up sharecropping and dived into art upon retiring at age 66.

"What I love about all these folks [is that] they make us see the world in a way we never saw it before," said Ellis, "which all great art should do." He began collecting works by self-taught artists during his time as a music writer in Memphis.

Ellis moved to Vermont in August 2011 to teach at Saint Michael's College after receiving his doctorate in ethnomusicology. He curated "This Was Me," an exhibit of works by artists affiliated with Hardwick community arts organization GRACE, at the New City Galerie in 2013; and "Looking Out: The Self-Taught Art of Larry Bissonnette" at the Amy E. Tarrant Gallery in 2015.

Blasdel's study of self-taught artists began at a young age. A Kansas native, he took an interest in the state's "outsider environments," he recalled. After graduating from the University of Kansas with a degree in painting, he received funds from Cornell University and the Whitney Museum of American Art to research and document similar environments created by self-taught artists around the country.

Blasdel initially came to Vermont in 1974 to finish a book about the outsider environment of Woodstock, N.Y.'s Clarence Schmidt. That book, titled simply Clarence Schmidt, was cowritten with then University of Vermont professor Bill Lipke and published in 1975 by the Fleming Museum of Art.

Blasdel remained in Vermont for a teaching position at Saint Michael's College, where he noted that his students tended to prefer self-taught art over "establishment" contemporary art. Asked why, Blasdel offered, "Perhaps because it's fascinating. It's so different; it's so out there. It's so in another realm."

Koch began collecting in the early '90s when she and Blasdel first got together. She's attracted to "the rawness of the vision," she says. "It's really contemporary art. I don't see a difference between self-taught and 'regular' contemporary art."

The couple's collection now includes hundreds of pieces, including more than 100 face jugs — the rough-hewn clay vessels first made by African slaves in South Carolina. Nine of them are on view at New City Galerie.

"It's been really fun to present the collection in a new way, to let it see the light and continue the dialogue," said Koch.

Innately Artistic

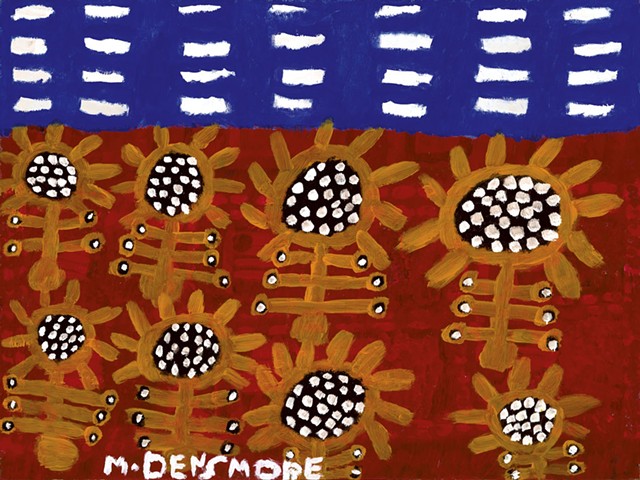

- Courtesy of GRACE

- Untitled painting by Merrill Densmore. Photograph by Paul Rogers Photography.

Just as "Grandma Moses: American Modern" works against the idea of Moses as a lone art-historical relic, so "Amazing GRACE" at Burlington's Amy E. Tarrant Gallery revels in presenting art as a demystified community practice. The exhibition offers 53 works by more than 20 GRACE participants, past and present, and celebrates 40 years of the center's nonprofit programming.

"Often art is a very personal, private thing," said GRACE executive director Kathryn Lovinsky, "but in GRACE workshops, [art] creates a larger community." The center offers 500-plus classes and workshops per year in nursing homes, mental health centers and adult day centers.

Now housed in an 1885 former firehouse in Hardwick, GRACE began in 1976 under the leadership of Don Sunseri. The artist, who died in 2001, wrote in a 1980s GRACE exhibition catalog that he came to Vermont in the early '70s to "get away from the competitiveness and hustle of the New York art scene."

Franklin identified GRACE as one of the "earliest progressive art studios in the country." In its mission to foster art making among community members who typically lack access to such activities, GRACE is a peer of other well-established studio art organizations around the country.

"Don believed very strongly that art is innate in everybody and just needs to be brought out," recalled GRACE creative director Kathy Stark, who joined the organization in 2000. "His vision was to have a mixture of people."

A broad swath of GRACE artists is represented at the Tarrant, but shared themes do emerge. Many works take the form of bird's-eye-view maps, such as Mary Paquette's intricately detailed, untitled pen-and-ink drawings; and Rowena Burnor's untitled watercolor. Human and animal figures populate both works on a flat plane among strictly demarcated areas: garden, building, road. Amid the not-to-scale scenes, both Paquette and Burnor insert a prominent human figure — perhaps the artist as viewer and documentarian.

Animals frequently dominate the exhibited works. In two untitled pieces from the 1980s, Phylis Putrain places birds within a series of brightly colored geometric marks and borders. The agglomeration of minute marks as a framing device resembles the technique developed by Dot Kibbee to border her tranquil landscapes. Curtis Tatro's blue colored-pencil drawing "Hazel the Horse" is uncannily similar to the work of Bill Traylor, the late canonized self-taught artist.

Many Vermonters are familiar with Aiken's quirky, energetic interpretations of her life in Barre, her passion for nickelodeons and her penchant for detailed captions. Stark recalled that Aiken used to refer to GRACE's headquarters as "The Gayleen Aiken Museum." Three of her small drawings are on view, along with five of her many cardboard "Raimbilli cousins."

Another artist popular among collectors is Merrill Densmore, a Northeast Kingdom painter who died in 2006. From GRACE's vast trove, several works were selected for exhibition here. Densmore's drawings alternate between detailed, mixed-perspective landscapes and more graphic compositions that approach abstraction. Many are rendered in loud colors, and all have thick, imprecise lines, reminiscent of the blocky, fantastical forms of Knight's Salvation Mountain. Franklin notes that he hopes to add work by Densmore to the Bennington Museum's permanent collection.

Flourishing in Vermont

Each of these exhibitions embodies the broad conviction shared by enthusiasts of the self-taught genre: that art is not just for the few, and that space for creative expression exists beyond the slim canon of art history and the market.

In a late 1980s essay on GRACE, art critic Lucy Lippard wrote, "Caught between the vulgar commercialism of mass-produced art on the one hand and an incomprehensible avant-garde on the other, between ubiquity and scarcity, people have to make their own art. In doing so, they comment on the failings of a culture that often fails them."

Grandma Moses capitalized successfully on the idea of Vermont's geographical and cultural isolation in the mid-20th century. In the 21st, commentators still invoke the rural nature of Vermont when considering work by its self-taught artists.

Andrew Edlin, a New York gallerist who took over that city's Outsider Art Fair in 2012, offered this: "Vermont is a place where there are so many isolated pockets and tiny little towns ... This is a fertile ground for outsider art and folk art to flourish, because people make art for their own reasons, without the audience necessarily being an important factor."

Edlin graduated from UVM in 1983 and now sits on the board of the Fleming Museum. He first became interested in self-taught art in his thirties, when he endeavored to sell art by his uncle, Paul Edlin, who was born deaf. Reportedly, attendance at the outsider fair has tripled under his leadership.

"I've seen this work go from zero to 100 in no time at all in terms of the market value," said Blasdel.

Collector Ellis noted another aspect of the Green Mountain State that fosters grassroots art: "There is a certain perspective in Vermont that appreciates the off-brand, the eccentric, the idiosyncratic."

The downside of self-taught art's mainstream acceptance, he added, is that "it has inspired a lot of faux folk art."

Vermont's exhibitions of self-taught art are important entries in the continuing conversation about whose creative production is valued, and how. Clearly, the state's art historians, collectors and makers are not isolated in the least.

Language Barriers

In a talk titled "Outsider Environments" at New City Galerie last month, Gregg Blasdel discussed the controversial nomenclature of self-taught art. He quoted Jean Dubuffet, the French grandfather of the genre, who dubbed it art brut: "Art does not lie down on the bed that is made for it; it runs away as soon as one says its name. Its best moments are when it forgets what it is called."

The history of outsider or self-taught art contains a dizzying array of art-world categories. Some other euphemistic terms used for it are "raw," "naïve," "vernacular," "visionary" and "intuitive." Many agree that "outsider" — a term introduced by British professor and author Roger Cardinal in his 1972 book Outsider Art — is potentially offensive and not particularly useful. But selecting more accurate alternatives has been challenging.

The effort is a long-standing one. Four years before Cardinal's book, Blasdel himself coined a different term in an article for Art in America magazine titled "The Grass-Roots Artist." The Burlington artist told Seven Days that he originally borrowed the phrase from abstract expressionist artist Alfonso A. Ossorio (1916-90), who signed a check with the note "For grass roots art."

Decades later, in 1993, art historian Jennifer P. Borum wrote in Raw Vision magazine, "Today it is virtually impossible to discuss a non-mainstream artist without wading through a perilous minefield of definitions." Borum suggested "self-taught" as a possible alternative.

At New City, "Exaltations" co-curator Bill Ellis offered his advice: "Do not get lost in the definitions — get beyond [them] and focus on the art."

Kathy Stark agrees. The creative director of Hardwick-based GRACE said that she "really hates labels," and expressed her hope for a world in which "we can just call it art."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.