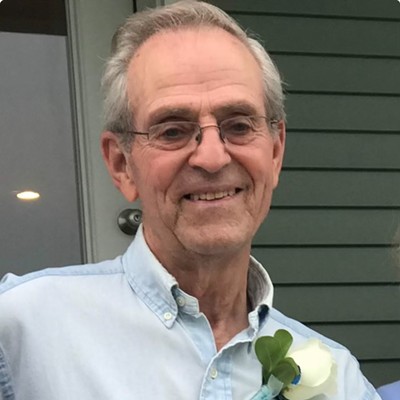

- Courtesy Of Lindsay Raymondjack Photography

- From left: Caitlin Walsh, Ry Poulin, Stefanie Seng and Aleah Papes in Translations

Woven throughout Brian Friel's 1980 play Translations is the profound matter of language itself. But the viewer's experience of the production is more likely to focus on the 10 characters whose hopes and foibles propel the play's comedy and drama. The story unfolds in the small County Donegal village of Baile Beag in 1833, and the period comes to life through the rustic set, evocative props and expressive clothes. Friel captures the satisfying rootedness of people whose identity is built on where they live, and director Cristina Alicea emphasizes their warmth and humor.

The setting is a rural hedge school for adults, a quasi-illegal operation at a time when England only permitted Anglican schools. This one is in the barn of the schoolmaster, Hugh, and his son Manus. The curriculum runs deep into Latin and Greek, the better to give Hugh occasions to quiz students on word origins and to afford the aged, perpetual student Jimmy chances to lose himself in the stories of Athena and Dido.

The story begins with language conjured from a woman with a speech disorder. With lovely patience, Manus coaxes Sarah to say her own name. Manus teaches in his father's shadow and keeps his Irish nationalism quiet as the Protestant and Catholic tensions simmer.

Britain's political initiatives reach the village in the form of an army ordnance crew that arrives to map the district and translate the Gaelic place-names into "the King's proper English." Friel uses a historical event to distill England's effort to subjugate Ireland, erasing names and thereby erasing history, memory and a cultural sense of self.

With the army comes Owen, Hugh's other son, now serving as the military's translator. Owen left the small village for the stimulation of Dublin and returns in fashionable clothes and with an ability to justify his work for the British, imagining he's staying one step ahead of his bosses.

The British Captain Lancey, his very mustache stiff with protocol, speaks English with a clipped cadence, so unlike the serpentine rhythms of the Gaelic-speaking residents. Lancey never cares that he doesn't know their language, but his lieutenant, George, finds the language and the countryside beautiful. George shows the humility of an outsider, not the bravado of a conqueror.

Owen's translations minimize the threat to the village that the army poses, a point not lost on Hugh and Manus, who speak both languages. Though Homer and Virgil are spoken in their native tongues, Friel's use of English for both Gaelic and English speakers presses the viewer to keep track of who can comprehend what. The audience is always privileged to know what's said but can't experience the exclusions that a language barrier creates.

The play's most powerful scene evokes the pain of not being understood. George not only adores the Irish landscape but falls in love with Máire, the dairymaid who wants to learn English and move to America. George and Máire express all the power of first love, relying on huge and heartfelt gestures to bridge their linguistic distance.

The romantic scene is passionate because both characters have only emotion, not words. But it's also funny, and Alicea and the two actors accomplish something powerfully human by mixing comedy and desire.

Alicea moves the large cast with assurance and creates a merry atmosphere onstage. The pace, however, can be too brisk for viewers to follow the curlicues of Friel's language and the unfamiliar accents and diction. Exchanges onstage are usually bright and clear, but descriptions of what's outside or abstract ideas can be hard to grasp. When in doubt, count on the atmosphere and the crisp, engaging performances for meaning.

The actors are always at ease in their surroundings, with a weight of truth to their characters amplified by costume designer Suzanne Kneller's excellent clothing. The Irish accents are convincing, thanks to dialect coaches Jordan Gullikson and Rover Sherry.

Quinn Post Rol is earnest and affecting as Manus, and Stefanie Seng brings a raw, feral power to Sarah. Harry Sheeran plays Owen with pure sparkle and a little edge of Irish sorrow.

As George, Zach Stark uses his height to proclaim the character's gangling shyness while also expressing a sense of wonder. Caitlin Walsh is a powerhouse as Máire, with the strength to survive and a deep ache to face life with courage.

Ry Poulin is perfectly mischievous as Doalty, a terrible student who's also terribly clever at sabotaging the army surveyors. As Jimmy, Mark Stephen Roberts is delightfully swept up by myths. Aleah Papes plays the wily Bridget with appealing pride.

Hugh is equal parts drunk, blowhard and aesthete, but Timothy Barden sometimes blurs these states together, leaving the character's thoughts fuzzy at critical points. As Captain Lancey, Kyle Ferguson conveys satisfaction with his work and has no trouble writing off those who stand in his way.

Jeff Modereger's set combines the sumptuous realism of painted texture with the stylization of boards and beams floating in space. Lighting designer Dan Gallagher by turns bathes the characters in a Rembrandt glow, then lets neon-green light leak through the chinks in the rough barn boards. The overall effect is otherworldly danger and instability intruding upon a bare-bones barn.

The play is a meditation on language as communication, identity and imagination. Jimmy swims in worlds described in Greek and Latin, eyes popping as he thinks of Athena, who's more real to him because of the language she emerges from. The logic George and Owen use to convert Gaelic place-names to English ones is ultimately arbitrary. As language keeps changing, history gets erased. What survives is the human spirit, and it's the people viewers will remember in Vermont Stage's production of this play.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.