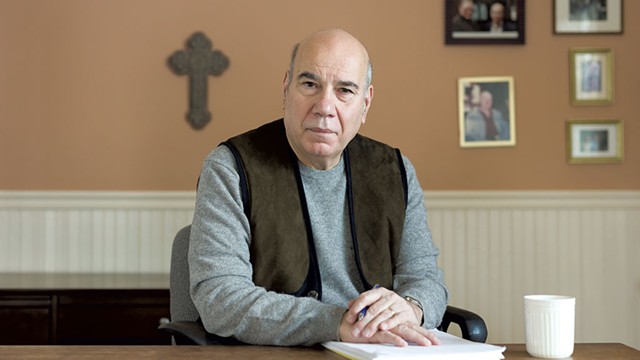

- File: Oliver Parini

- Jay Parini

"I think Weybridge may now have more writers than cows," speculates George Bellerose, the administrator — and multi-year winner — of the Weybridge Haiku Competition.

He just might be right. According to Bellerose, the number of entries to the contest has increased by a whopping 278 percent since it began in 2018. The U.S. Census Bureau puts the Weybridge population at 821; the poets among them keep coming out of the woodwork.

Held virtually by necessity this pandemic year, the previously local competition opened to, essentially, the entire world, and it drew entries from as far away as Croatia. Still, most of the poems came from Weybridge itself.

The delightfully eccentric competition was the brainchild of two residents who, in addition to teaching at Middlebury College and serving as co-poet laureates of Weybridge, also happen to be literary luminaries. Author Julia Alvarez received the National Medal of Arts from president Barack Obama in 2015; Jay Parini is a Guggenheim Fellow whose best-selling novel The Last Station was adapted into an Oscar-nominated film. (One of the most interesting details on Parini's résumé: driving Jorge Luis Borges around Scotland while evading the Vietnam draft, which became the subject of his latest book, Borges and Me: An Encounter.)

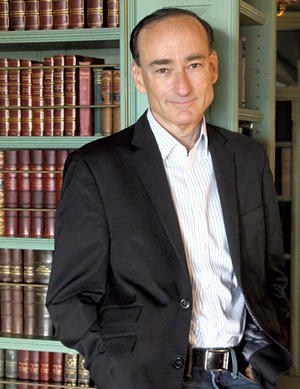

- Courtesy Of Bill Eichner

- Julia Alvarez

In the past, the winning haiku would be recited at the annual town picnic in July, an occasion that also included live music and a barbecue. This year's winning entries have been announced early, in conjunction with National Poetry Month. Following the perhaps inevitable contest theme, "Life During the Pandemic," the haiku also serve as a poetic document of our plague year. In clear, concise language, they record grief, isolation, hope and solidarity.

Ellen and Erika Bodin, of North Chittenden, took home first prize in the Vermont Winners category of "Best Mother/Daughter Duet Haiku-Writers" — one of 26 amusingly specific categories devised by Alvarez for each of the entrants. Ellen wrote the first, Erika the second:

the sparrow singing

its heart out — neither of us

with places to go

I am dancing and

you are the song though sometimes

I cannot hear you

Though Alvarez and Parini will remain as consultants, 2021 marks their last year as judges. Next year, another member of the Weybridge literati, novelist and journalist Chris Bohjalian, will take up the mantle. Best-selling author of 20 books translated into dozens of languages, he'll team up with one of this year's first-place Vermont Winners, Martha Winant, and Narges Anzali, a high school student and new youth poet laureate of Weybridge.

What exactly is haiku?

- Courtesy Of Victoria Blewer

- Chris Bohjalian

If you answered, "A three-line poem written with five, seven and five syllables per line," you'd be correct, but only as defined by the broad and somewhat arbitrary interpretation of Japanese literature that most of us were taught in elementary school. In fact, there's much more pleasure to be had in writing haiku than simply counting and dividing up syllables.

As a longtime lover and occasional practitioner of haiku — and something of a haiku truther — this writer feels obliged to provide a more expansive definition than the reductive 5-7-5 format. First of all, Japanese and English are so different linguistically that the units of sound counted in Japanese, called on, do not equate to English syllables, either mathematically or rhythmically. For example, in Japanese poetry, the word "Tokyo" counts as four on.

Traditional haiku also employ a kigo, a seasonal word, and a kireji, a "cutting word," which is used to separate the two images that the poem depicts, sometimes paradoxically. The 17th-century haiku master Matsuo Basho wrote:

In Kyoto,

hearing the cuckoo,

I long for Kyoto.

Rules, of course, are made to be broken. And we aren't in Edo Period Japan. However, reducing a thousand years of a culture's literary tradition to 17 syllables is a double-edged sword. To be sure, it provides a welcoming entry point into poetry for anyone who might be intimidated by longer rhyming forms such as the sonnet. Yet by focusing solely on syllable count, the whole essence of haiku — juxtaposing two concrete images in order to convey a complex idea or emotion without describing it directly — gets lost.

For anyone interested in contemporary haiku in English, online magazines Modern Haiku and Frogpond provide plenty of background on the nuances of the tradition and its evolution.

But this is not to say the Weybridge Haiku Competition doesn't adhere to tradition: The form itself evolved from haikai-no-renga gatherings in Japan, where people would collaborate and compete with linked verses. Basho was a haikai master, holding contests at his hut when visitors congregated there. It's a testament to the power of poetry that his spirit has lived on, manifesting centuries later across vast oceans, to guide the citizens of a small Vermont town.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.