- Gary Causer

CONGRATULATIONS to Jeremiah Cook of Burlington for taking top honors in the 2002 Seven Days Emerging Writers Competition, co-sponsored and underwritten by the Professional Writing Degree Program at Champlain College. His story, “The Ventilator,” is printed on these pages. He will also take home a $250 cash prize, proving that writing fiction can pay, however modestly.

The runner-up this year is Roberta A. Harold of Montpelier for her story, “In the death of the soul there are no suspects,” and close behind in third place is Eli Trudeau of Burlington for “Love Song.”

All three are strong and well-written tales, and they represent the quality and diversity of this year’s entrants — among them is writing good enough to buoy our faith in the future of the printed word.

We’d like to profusely thank everyone who bravely shared their fiction, and their aspirations, with us. To you we say: Write on.

Last but not least, we extend a warm thanks to those whose collective works remain an inspiration to us all — our esteemed judges:

• Philip Baruth teaches English at the University of Vermont and is a commentator on Vermont Public Radio. He has published a book of short stories and two novels. He also recently co-edited, with Burlington writer Joseph Citro, Vermont Air: The Best of the Vermont Public Radio Commentaries.

• Shelby Hearon is a Burlington novelist whose latest book is Ella in Bloom, recently out in paperback.

• Elizabeth Innis-Brown is the author of two books of short stories and the recent novel, Burning Marguerite. She teaches writing at St. Michael’s College.

• Tom Paine lives in Charlotte and teaches at Middlebury College. His book of short stories, Scar Vegas, was published in 2000. His first novel, The Pearl of Kuwait, is due in February.

• John Rubins is the Bristol-based editor of the online fiction monthly, Tatlin’s Tower (www.tatlinstower.com). His own writing has appeared or soon will appear in Surgery of Modern Warfare, American Journal of Print, The Southeast Review, elimae and Seattle Weekly.

The public is invited to a reception and reading with Jeremiah Cook, Roberta Harold and Eli Trudeau this Thursday, June 27, 7 p.m., at the Morgan Room in Aiken Hall, Champlain College, 83 Summit Street, Burlington. The event is free.

The fall that I was nine years old, the oil furnace in our house on West Church Street in Hardwick broke down. Over Saturday breakfast, my father announced that he’d struck a deal to buy us a used woodstove. This explained why he’d come home with two cords of cut and split hardwood the evening before.

“It’ll save us a bundle on heating costs,” he said.

“Where are you getting this woodstove?” my mother wanted to know.

“Up on Bridgman Hill,” said my father. “Guy named Prew.”

“Bruce Prew?” asked my mother. My father nodded.

“Prew’s a Buddhist,” she told him.

“Don’t care what he is,” said my father, getting up from the table.

After he’d left the kitchen my mother turned to me. “Never buy a woodstove from a Buddhist,” she warned.

I nodded solemnly. I didn’t want her to know that I wasn’t sure what a Buddhist was.

At ten o’clock that morning, a pink and gray Volkswagen Microbus pulled into our yard. A huge, tan, metal box stuck out lengthwise about a foot and a half beyond the bus’ open sliding side door. The driver was a tall, thin man with a long, scraggly beard and hair pulled back into a ponytail. He shook hands with my father and winked at me. He had gentle, light-blue eyes.

“This is my boy, Lester,” my father said.

“Hi, Lester. I’m Bruce,” he said.

Bruce the Buddhist, I almost said. I nodded instead.

“How the Christ’d you get that sucker in there?” my father asked, looking in at the stove through the windshield.

“I had some help loading it in last night,” explained Bruce. “I think the two of us can manage it if we take it easy.” I liked the soft, easy way he spoke.

My father was a small, balding man. He was shorter than Bruce and definitely no heavier. The stove looked heavy and cumbersome. I could tell it was going to be a production to get it into the house. My father had a quick temper, which usually came out whenever there was any kind of important, heavy task to be done. My mother and I brought out two folding metal chairs and set them up on the porch to watch. It was October, but it felt nice sitting next to my mother with the sunshine on my face.

Just getting the stove out of the Microbus and onto the ground took them about fifteen minutes, using two-by-fours as levers. Once the woodstove was about halfway out, my mother and I began to see what it looked like. It looked like an old-fashioned stereo console, the kind where you opened the wooden top to get at the record player and knobs inside. The face of it was a mesh screen made of a lighter colored metal than the rest of the stove. The screen looked like a large speaker. At the top of the metal screen there was attached a thick chunk of chrome that announced the stove’s name. VENTILATOR, it read.

My mother looked down at me. “Ventilator means maker of wind,” she told me. “Never buy a woodstove whose name is derived from Latin.”

I nodded my head slowly to show that I was in steadfast agreement with this wisdom.

By the time they had the Ventilator on the ground in front of the porch stairs, my father had started cuss-mouthing a mile a minute. At one point Bruce interrupted his curse words and said, “Hey, hey, hey.” It was like he was saying, watch your language, pal; I’m a Buddhist over here.

I whispered to my mother, “Never swear in front of a Buddhist.” She made a tight-lipped smile at me.

My father and Bruce spent a while walking around the stove and discussing whether or not it would go through the front door. My father seemed to think it would; the Buddhist was pretty sure it wouldn’t.

“I think there’s a tape measure in the kitchen drawer,” I called down to them. “If that’ll help.”

“What’ll help is if you keep your damn trap shut,” said my father.

“Hey, hey, Clare,” said Bruce. “Take it easy, huh.”

My father’s name was Clarence. I believe the Buddhist was the only person who ever called him Clare, like a kind of shampoo, or a girl’s name. My father didn’t care for it. By the time they had the Ventilator up the stairs and blocking the front doorway, which was three inches too narrow to take the stove, my father had cuss-mouthed more in ten minutes than I had heard him do before in the entire nine years that I’d known him. He stood, red-faced and sweaty, looking at his woodstove. “Piss hole!” he shouted at it, then he kicked it.

“Hey,” went Bruce the Buddhist, “just take it easy. We’ll work it out.”

“Don’t you gimme none of that tofu,” snapped my father. He pointed a finger at Bruce, not so much at his face as at the tip of his long beard. “I ain’t in the mood for it. See what I’m saying?”

“Not in front of Lester,” scolded my mother, clapping her hands over my ears.

Bruce saw what my father was saying. Without a word he turned and descended the steps, climbed into his bus, and backed out of our yard. That pink and gray Microbus, with its sliding side-door that he’d forgotten to shut, put me in mind of a big clown with his mouth hanging open.

“How much did you pay him for this?” my mother asked my father, tilting her head at the massive Ventilator trapping us outside of our house.

My father was on the other side of the stove. He would have had to crawl over the top of it if he wanted to use the stairs. He let himself over the porch rail and jumped down. “Don’t really matter, does it?”

“Doesn’t really matter! Doesn’t really matter!” shouted my mother, holding her hands over my ears. My father dismissed her with a wave, and stomped off to the other side of the house to open up the bulkhead to the basement so we could get in.

When my mother took her hands from my ears, I finally got to say something I’d been dying to say. “Never point at a Buddhist,” I said. My mother leaned in and kissed my forehead.

My father ran chainsaw for a living. He worked on Marsilius Malagigi’s cutting crew, clearing power lines mostly. Two of the biggest guys on the crew were Bump Putvaine and Lou Mosse, who’d both been chums with Clarence back in high school.

After he got inside the house by way of the basement bulkhead, my father called them both. Next, from inside, using a hammer and chisel, he went to war with the front door. I came in to watch.

“Where’s your mother?” he asked.

“She went to Aubuchon’s.”

“What for?”

“She said an electric space heater.”

He snorted. “Well, ain’t that just pissing money into the wind.”

Instinctively I reached up and covered my ears. My father gave me a look, then whistled at me and went back to work.

By the time Bump and Lou arrived, my father had pried off the entire doorframe, then taken his Husqvarna to the wall itself. He’d fired it up right there in the living room, then hollered out, “Boy, we’re getting a new door!” Then he’d gone ahead and sawed an extra three inches into the front door opening, shooting plaster and shreds of wallpaper all over the place. If my mother had been home, there might have been words.

“First thing,” he told Bump and Lou when we met them outside, “that big box whore is going in.” He pointed at the Ventilator. Bump and Lou were enormous men. They made Clarence look like a dwarf. The two of them had big, powerful arms. Bump had a short red beard and he wore a cap that said, Don’t argue with your wife, just dicker. Lou had a big black mustache. Watching Clarence was like watching a gnome point out a UFO to two confused giants.

“Where’d you get that?” Bump asked my father.

“Guy up to Bridgman Hill. Saw a sign for it, so I went and checked it out. It ain’t brand-new, but it’s supposed to give off heat slick as shit.”

Unable to stop myself, I reached up and squeezed my ear lobes. Then I tried to help explain things. “He got it off a Buddhist,” I told them. They both looked down at me like I was out of my mind.

It took my father’s huge chums about a minute to get the stove in. With the two of them lifting it, the Ventilator looked much smaller, more like a cedar chest or a breadbox. My father had them put it against the chimney that ran up through the living room from the basement. When Bump and Lou set it down it looked big again, making the living room seem crowded.

“See?” said my father. “There’s already a flue cut into the brick.” He pulled the six-inch tin circle cover from the face of the chimney, exposing a dark, crusty hole. “Alls I need is a length of stovepipe and an elbow. Bang, done. Free heat.”

“You’ve still got your central oil for backup?” asked Lou.

“Ain’t gonna need it,” snapped my father.

Bump and Lou both looked down at their shoes. I pretended to dig at wax lodged in my ears.

My mother came in through the door to the basement carrying two brand-new electric blankets wrapped in clear plastic. She took one look at the Ventilator and frowned. She shook her head at Bump and Lou, as if it was all their fault, and went to the stairs. She paused in front of our hacked, splintered, naked, door-less doorway for a moment before going up.

The Ventilator had to be plugged in, because there was a fan beneath the firebox that was supposed to blow the heat out of the metal screen and into the room. The firebox door was at the side of the stove. My father was displeased to discover that the opening to the firebox was smaller than a lot of the hardwood he’d cut and chopped over the past week. He spent a while opening and closing the firebox door and cuss-mouthing into the stove’s belly. It had been a day of openings that were too small.

That evening, once he’d installed a length of stovepipe and an elbow, my father went about lighting a fire.

“Did you ever make a fire in a stove before?” I asked him.

“Any peckerwood can light a fire. It’s keeping it stoked right what’s important.”

“That’s important,” corrected my mother from the couch, not looking up from her reading.

My father whistled at her and began crumpling up sheets of old Hardwick Gazettes into little balls. He placed ten of these inside the belly of the stove, then, on top, he put ten pieces of dried kindling wood. He lit a match, touched it to the newspaper, closed the firebox door and cried, “Ya-hoo-boy!”

The growing fire inside the stove sounded like a chugging locomotive, and after a few minutes I could feel the heat starting to come from the metal screen. My father was practically jumping up and down. After another minute he shouted, “Here we go!” and reached down behind the Ventilator to hit the switch for the fan. There was a terrific grinding noise followed by a steady plume of black smoke pouring out of the metal screen and into the living room. My father turned off the fan and stayed crouched down behind the stove trying to get a look at what was the matter.

My mother coughed, got up from the couch and said, “That’s pleasant.” Then she carried her reading out to the kitchen.

I woke up Sunday morning to the sound of my father on the telephone. “You puke, Prew,” he roared. “You come and take this smoke box today, and you give me back what I paid you. And I don’t mean no check, neither. See what I’m saying?”

It was a sunny day outside, but as I lay there beneath the brand-new electric blanket my mother had spread over me the night before, I could just make out the steam of my own breath dissolving in the air above me. There was a breeze blowing. I knew this because I could hear the flapping noise made by the sheet of plastic my father had staple-gunned over the front doorway.

When the pink and gray Microbus pulled into our yard at four o’clock that afternoon, I became nervous about what might happen. I hid around the corner of the house listening but unable to watch. I felt sorry for Bruce Prew. I thought he meant to sell us a good stove. My father was just unlucky around mechanical things, though he could never accept this fact. I liked the Buddhist, with his soft eyes and calm way of talking about things. I was afraid my father would hurt his feelings.

“Clare,” said Bruce, “I can’t tell you how sorry I am about this.”

“Well, not hardly so sorry as I am. Christ, the thing blew smoke like a fart in a chokehold. What the flying crap am I supposed to think?”

I summoned the courage to take a peek. Bruce stood about five feet away from my father, looking devastated. When he stepped forward and began counting bills into my father’s open palm, I got a sick feeling in my stomach that stayed there the rest of the day.

“I don’t think I’m up to trying to move the stove today,” said Bruce. For a second it looked like he might cry.

“When, then?” said my father.

“Tomorrow morning?”

“Got to work in the morning.”

“Bright and early, then.”

“You do that.” My father crossed the lawn and climbed the steps. Earlier that day, he’d taken a knife and cut a slit down the length of the plastic over the doorway.

“Hey, Clarence,” Bruce called from over by his bus. My father turned. “I really am sorry.”

“Yeah, well…” said my father. He shrugged, then passed through the slit and into our house.

When Bruce Prew did not show up the next morning, my father cuss-mouthed all through breakfast, then went to work. That evening, he tried to call but there was no answer. Over dinner, my mother urged him to discuss what we were going to do about heat, and he told her he was too agitated to get into it.

The Ventilator sat cold and quiet in our living room for two weeks, during which time we had two light snows.

On the Saturday that I was awakened by all sorts of racket — clanging, banging and swearing, which seemed to come from all over the house — I leaped from bed and ran downstairs. The Ventilator was gone. Through the living room window I could see Bump and Lou and my father loading the stove up onto the bed of Bump’s big blue F350 pickup. Parked in front of Bump’s truck was a white van that had Fosters Gas and Oil written on the side in red cursive. I ran into the kitchen, where my mother was at the range in her bathrobe making scrambled eggs.

“What’s happening?” I asked her.

“They’re fixing the furnace,” she told me, not turning around. “Your father and his dancing bears are loading up the woodstove so they can take it to the dump.”

“The dump? Can I go?”

“Is that how we ask for permission to do things?”

“May I please go to the dump?”

She set down a plate of eggs in front of me. “We’ll see,” she said.

The Hardwick Landfill was one of the most wonderful places in the world. There were acres of smelly trash. There were tons of neat stuff that nobody wanted anymore, like Radio Fliers missing wheels, and Six Million Dollar Man dolls with no arms. There was a huge yellow front loader that drove around smashing the things that were already smashed.

The man who ran the dump and drove the front loader was an old guy who smoked a pipe, walked with a limp and talked like a frog. My father and Bump and Lou all called him Popeye. When we pulled in and stopped at the little shack next to the gate, my father and Lou got out to talk with him. “You wait here with Bump,” my father told me.

After a little while Bump revved the engine impatiently. He looked down at me sitting next to him. “How’s your marksmanship these days?” he asked.

“I guess pretty good,” I said, having no idea what he meant.

After my father and Lou came back, we drove deep into the landfill, past the great piles of green garbage bags, past the scrap wood area, past the scrap metal area. When we stopped, we stayed in the cab a while looking out over a flat muddy section at the very end of the dump. Beyond it there were only pine trees. I sat squished between them keeping quiet while they drank cans of beer and talked about work.

Finally Bump started the truck. He drove out into the muddy clearing, made a circle and brought us back to where we were, only we were facing up into the dump.

When we got out I could smell the dump in full force. I knew it was supposed to be a bad smell, a rotten smell, but I liked it. There was something right about it, the same way there was something right about the smell of cow shit whenever we went to visit my Uncle Burt’s dairy farm.

My father and I watched as Bump and Lou pushed the woodstove over the edge of the tailgate. It landed on its face with more of a thud than the crash I was expecting. Then the three of them did something I couldn’t understand. They got down and lifted it upright. There was a big dent in the screen, and a lot of dirt had lodged into the mesh. I thought about going up to it and wiping away the grime with the sleeve of my jacket, but Bump was already back in his truck pulling forward slowly.

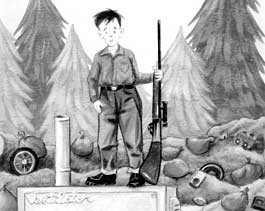

“Come on,” my father said to me, and we tagged along behind the truck. When we caught up, Bump had shut it off and was pulling three long canvas bags out from behind his seat. These, I knew, were rifles. A few years before, my father had had a rifle that he kept in a canvas bag, but he sold it so he could buy his new Husqvarna. Why were they going to shoot the Ventilator? I wondered.

“Now you stand clear, and don’t try anything cute,” my father warned me once we’d all climbed up into the bed of the pickup. I had never been close to guns being fired before, and I was startled by how loud they were. It was like they were in a race to see who could shoot the most times. Quickly the stink of the dump was replaced by the burnt-chemical smell of gunpowder. In no time they’d shot the woodstove full of holes. Each time a small piece of it went flying off, somebody whooped like they’d done a great thing. Then they all stopped and opened fresh cans of beer.

“Lester, you want to give it a try?” Bump asked me.

I didn’t say anything at first. I looked at my father. He looked at me, then at Bump and Lou, then back at me. “Okay,” I said.

“Well, all right,” said Bump. Lou gave me a slap on the back. I saw my father wink at the two of them.

We got off the back of the truck and went much closer to the stove. The metal screen had dozens of holes shot into it. Someone had hit the chrome VENTILATOR sign, shot off the end of it, so that now it only read VENT.

Bump handed me the smallest of the three rifles. It felt hot and heavy in my hands. “When you lift the rifle,” said Bump, “put the butt in snug against your shoulder,” he said, “not against your arm. Steady it nice and easy, and tilt your head in to line your sight.” He showed me how to do it with his own gun. “Don’t forget to breathe,” he told me. “When you take your shot, don’t herky-jerky it, just squeeze it off nice and slow. See what I’m saying?”

Looking down the length of the gun, I got a funny taste in my mouth, unlike anything I’d tasted before. I aimed for the chrome VENT. I heard them slurping their beers above me. I thought of the Buddhist, and how seeing his stove all shot up would make him feel. Then I shot. I don’t know which surprised me more, that the rifle pushed me backwards or that I shot the VENT clean off.

“Jesus, Clarence,” said Bump. “Kid’s a better shot than you are.”

There was laughter. Lou handed me his beer to sip. My shoulder was sore.

“You ought to take a week off from school next month, Lester,” said Lou. “We’ll get you up to deer camp.”

“Mom won’t let me,” I said.

“Yeah, well…” my father said, trying to laugh.

We were cut off by a loud diesel engine coming up behind us. We stood and watched Popeye drive the front loader up to the ruined stove and bring the bucket down onto it three times. He crushed it against the earth so that you could not tell what it had once been. Then he scooped it up, gave us four a wave, and drove off with it in the direction of a pile of junked refrigerators and washing machines.

Part of me wanted to whoop for joy, like a man who’d just climbed a tall mountain. Another part of me felt sick inside. The Ventilator had meant no harm.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.