- Rachel Elizabeth Jones

- Cameroon water buffalo mask

At the beginning of the 2018 box office hit Black Panther, a young African man stands before a glass case of West African masks and weapons in the (fictional) Museum of Great Britain. "How do you think your ancestors got these?" he asks the prim white curator. "Do you think they paid a fair price, or did they take it, like they took everything else?"

As museums around the world increasingly become the sites of heated public debate on colonial histories, an exhibition at Burlington's Amy E. Tarrant Gallery offers a more nuanced and exceptional story of collecting, and sharing, African art.

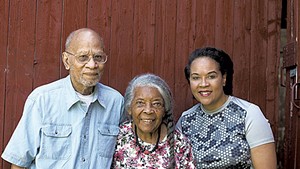

"The Intrepid Couple and the Story of Authentica African Imports" opens a window onto the life of Jack and Lydia Clemmons, a trailblazing African American couple who purchased a Charlotte farmstead in 1962.

- Rachel Elizabeth Jones

- Jack and Lydia Clemmons

The exhibition was curated by Lydia and her daughter, also Lydia Clemmons, with the encouragement of former Flynn Center for the Performing Arts executive director John Killacky. It uses a selection of African art and ceremonial objects, accompanied by text and recorded family storytelling, to celebrate the path the Clemmonses wove between Vermont and Africa.

Collected over several decades, the works on view range from a Cameroonian water buffalo mask to Tanzanian butterfly-wing "paintings" to West African trade beads and Ghanaian kente cloth.

The Clemmonses first traveled to Africa in 1984, when they were in their sixties. Jack, a pathologist at the University of Vermont, was offered a position researching the then-mysterious HIV virus at what is now the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre. Lydia joined him, working as a nurse anesthetist. Thus began the couple's 20-year era of travel throughout the African continent, which led to the incidental birth of the first African retail mail-order business in the U.S.

- Rachel Elizabeth Jones

- Authentica shop sign

"They worked in the hospitals," recalled daughter Lydia, "and then, being who they are, on the weekends they wanted to go explore." Lydia Sr. said of their white counterparts: "They were afraid of the population. At first my husband and I listened to them, and then we looked at each other and said, 'Wait a minute. We're just like these people, so what are we afraid of?'"

By that time, the couple already had experience traveling in an arguably more dangerous place. One section of the exhibition is dedicated to their 1953 honeymoon journey, a road trip from Madison, Wis., to Los Angeles and back. Segregation was legal; with limited options for lodging for black Americans, the Clemmonses camped. Though The Negro Motorist Green Book had been published a few years earlier, exhibition text explains, the Clemmonses did not know about it.

- Rachel Elizabeth Jones

- Tanzanian butterfly wing painting, detail

On the gallery's western wall hang two colorful sisal-fiber bags, a popular item in Kenyan marketplaces. According to the Lydias, these totes "started it all": Lydia Sr.'s UVM hospital coworkers loved them and ordered more through her. "They just went off like hotcakes," said Lydia Jr. "They sold so quickly when Mom came back — and suddenly there were containers coming."

What began as an informal exchange among friends at the Clemmons family's kitchen table grew into a full-fledged business; Jack transformed the 18th-century blacksmith's shop on the 148-acre farm into a rural storefront. They named the business "Authentica" after a young Kenyan woman who had become a business partner and friend.

As Lydia Sr. explains in one of several audio recordings at the gallery, it was important to her that her imported goods be of "museum quality." "Every single piece was so lovingly collected through the adventures of my parents [and] their relationships with vendors," said Lydia Jr.

Operating as both a gallery and store, the shop became a popular destination for local elementary school classes, as well as for Africans and African Americans feeling isolated in Vermont, historically one of the country's whitest states.

As Lydia Jr. put it, "[Imagine you] see fabrics from Africa and then see this black woman there who looks like your mother! It was just such a relief that such a place existed ... A lot of Africans who may have been customers, but more [often] became friends and collaborators, fell into my mom's arms."

- Rachel Elizabeth Jones

- Photograph of Jack and Lydia Clemmons, circa 1953

Though Lydia Sr. closed the store in 2012, the Clemmons Family Farm has continued to grow into its role as a hub for black Vermonters and African American culture. In 2017, the farm received a $350,000 grant from ArtPlace America's National Creative Placemaking Fund to aid its transition from a private, family-owned farm to a nonprofit cultural center.

"We actively promote the deeper understanding and appreciation of African American and African diaspora history, arts and culture," says the center's website. Lydia Jr. noted that she hopes the Tarrant Gallery exhibition will help serve this mission, "especially [for] African Americans who don't know a lot about their own history.

- COURTESY OF JOHN Y. FLANAGAN

- Fang tribe wooden mask, Southern Cameroon, circa 1800s

"Our position is that no object is as important as the story and people behind the object," she continued.

The story that stands out in this show is the extraordinary path of Jack and Lydia, a couple who made their life an adventure — a luxury that a white-centric society made it hard for African Americans to afford.

"[My parents] were constantly doing things that were not usually done," said Lydia Jr. "They approached Africa the same way, with bold optimism and eagerness and love and, I think, a lot of good luck — because they were never hurt, which was a real possibility."

Though she travels far less than she used to, Lydia Sr. remains as engaged and upbeat as ever. "I'm having a wonderful time in my nineties," she said, "because I read and do whatever I want."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.