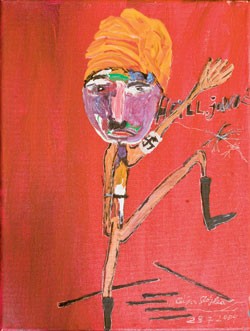

- "The Dance on the Swastika"

Ceija Stojka cannot forget her traumatic childhood; as an artist, she has reason to remember. A touring exhibit of her paintings, currently at the West Branch Gallery, illustrates the horror of her early years.

Stojka is a Holocaust survivor. In 1933, the year she was born, Nazi leaders began to actively persecute her people, the Lovara, a traditional horse-trading tribe of the Roma. Two years later, the German government determined that the “Gypsies” had “foreign blood,” and by 1938, Roma children in Austria were forbidden to attend school.

In 1940, Stojka’s family was taken in by Viennese friends, but within a matter of months her father was arrested and sent to Dachau. A year later he was murdered at Tiergartenstrasse 4 in Berlin, where Nazi doctors performed euthanasia experiments.

Stojka was 8 years old when she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the first of three concentration camps she survived, along with Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen. By the time the war was over, young Ceija, three siblings, her mother and aunt were the only living members of their erstwhile 200-member clan. She attributes their survival to her mama’s injunction to eat anything they could get their hands on — dirt, grass, leather and bark.

The authors of The Holocaust Encyclopedia estimate that 220,000 Roma, or one-quarter of the total population of Europe’s nomads, were killed during the Nazi occupation.

Stojka, now 76, has dedicated the last 20 years of her life to telling her people’s Holocaust story through poetry, autobiographical writing, painting and drawing. Though her work has been shown in Austria, where she lives, and elsewhere in Europe, she had not exhibited in the United States until this year. Dr. Lorely French arranged for Stojka’s work to be shown at Pacific University in Oregon, where she teaches, at Sonoma State University in California, and at the West Branch in Stowe.

Stojka’s acrylic paintings and pen-and-ink drawings are visceral re-creations of her experiences in the concentration camps. Her nightmarish tableaux are replete with images from her torturous memories of gun-toting SS henchmen, children dying around her, and the naked, emaciated figures of Roma women.

She writes, “I, Ceija, say Auschwitz lives and breathes still in me today.”

The constant torment of the living hell in her mind takes haunting form in her crude style: Stojka uses her fingers and toothpicks instead of brushes to apply the paint and ink. This lends the work an eerie, childlike quality that makes even more horrific her depictions of the day-to-day anguish of living under constant threat of dying from starvation or the gas chambers.

The specter of Hitler pervades Stojka’s work. The Führer is there in glossy black knee-high boots, in her finger painting titled “The Dance on the Swastika.” His demonic spirit possesses her depictions of the blond, whip-wielding prison guards in “Binz.”

Stojka’s image of Hitler is garish and otherworldly. He is a stick figure with an oversized head, and he stares owl-like at the viewer while his body goosesteps in the opposite direction. The background of the painting is blood red; guns litter the ground beneath his feet.

Stojka, who is self-taught, didn’t begin to make art until she was 56. She suddenly felt compelled to paint and draw and used the materials at hand — pieces of cardboard, glass jars, postcards and salt dough. “I work with everything that comes between my fingers,” she writes.

On good days, Stojka paints flowers — roses, sunflowers, strawberries and fields of wildflowers — or depicts her memories of living out of a horse-drawn caravan with her family before and after the war. On bad days, when she thinks about her father or her brother, who died in one of the camps, memories of the cattle cars, the smokestacks at Auschwitz, and Nazis corralling women and children pursue her.

Stojka’s work is rooted in German expressionism and folk art. In “Dying Children,” the faces of babies, toddlers and teens float in space, like spirits lifted from a clouded memory. In one of her more lurid scenes, “Women’s Camp Ravensbrück,” a wagon is loaded down with bodies, and the faces of the dead already look like skulls. A woman raises her arms and appears to call out to a young boy in the foreground who holds the body of a dead child. Nazis with dogs watch the scene, and a dirty snow covers everything — the low-slung barracks, large pine trees, brambles and the strings of barbed wire that appear in nearly all Stojka’s works.

These scenes are not easily forgotten.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.