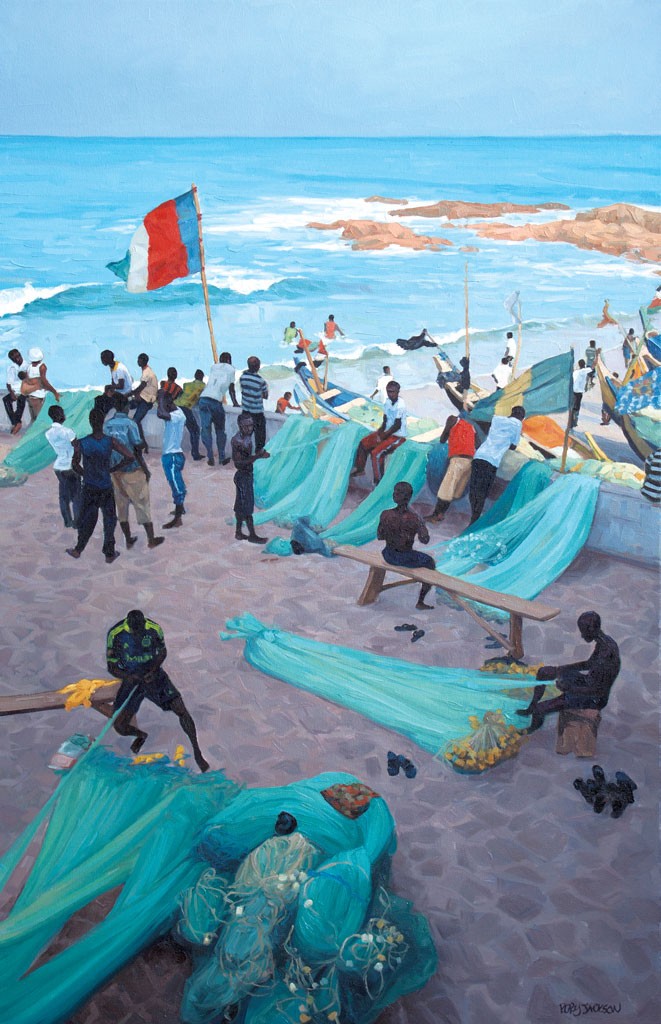

- "Waiting for the Black Star Liner"

Rory Jackson first traveled from Vermont to Ghana at age 14 on a transatlantic field trip sponsored by Mount Abraham Union High School. His aim was to study percussion with African master drummers, but by that time he was already turning his attention to painting.

Visual artistry runs in the family. Jackson's uncle, Woody Jackson, created the image of lazily grazing Holsteins reproduced on Ben & Jerry's ice cream packaging and trucks. Rory's mother, Anne Cady, paints stylized Vermont landscapes in fauvist colors. And one of his three siblings, Bristol-based furniture designer Josiah Jackson, built the handsome frames for a set of six paintings of coastal Ghana that Rory completed this year.

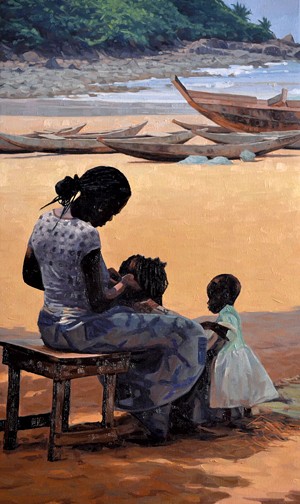

Middlebury's Edgewater Gallery, which represents Rory Jackson, offered those pieces for sale at last week's Affordable Art Fair in Manhattan. In a technically deft realistic style, they depict fishermen repairing nets, setting out to sea and relaxing on a boat. Another painting in the series shows a woman braiding the hair of a young girl while a toddler in a long, white dress looks on. In yet another scene, pastel-colored towels and laundered bedsheets dry on a clothesline and a lawn. Each of the images is aglow with a tropical radiance.

For much of the past two decades, Jackson, 32, has straddled the culturally and climatically dissonant worlds of Addison County and West Africa. He lives mainly in Lincoln with his Ghanaian wife, jewelry maker Rita Agyemang, and their two children, ages 9 and 6. Jackson paints local landscapes in his studio in Bristol, where he offers weekly instruction in figure drawing. The family travels regularly to Ghana to visit relatives. They also check up on the vocational and academic high school Jackson founded eight years ago in Cape Three Points, a remote, impoverished area with long, empty stretches of sandy and rocky beach.

- Rory Jackson

The waves on the cape often break in thunderous funnels — a key motivation for the dreadlocked artist and surfer dude to build his school on a ridge overlooking the ocean. Jackson was on this side of the Atlantic last week — on a surfing vacation in Costa Rica — when Seven Days spoke with him by phone.

SEVEN DAYS: So, which is more important to you, Rory — surfing or painting?

RORY JACKSON: They're different realms, man. Surfing for me is like getting everything released. I don't have to work for anything when I'm out there, except for my survival. Painting is where I have to work to survive in all sorts of ways. It's hard to make a living as an artist.

SD: How did you get started as a painter? Was Woody an important influence?

RJ: I learned art as a little kid at an after-school program in Middlebury run by my mother. She also taught my brother, Josiah, and my younger sister, Justine. It provided an artistic lens for all of us.

I did a lot of work on my own in high school. My art teacher at Mount Abe told me to just go out on my own and do it — that I got the basics.

I also took some classes at the Art Students League in New York, particularly with Max Ginsburg [a painter of realistic, often politically inflected urban scenes], who I still study with. His approach with color and brushwork felt like the direction I wanted to go. He's very much a hands-on teacher who helps you learn the tools. There's no BS.

Woody is an important influence because he's quite successful in the arts, as well as a close relative. He pushed me to keep focused on art, always encouraging me and saying I was better at it than him.

SD: You didn't have much formal training as a painter. At the risk of sounding boastful, would you say you're naturally talented?

RJ: I look at painting like cooking. Some people have to measure everything out and go carefully; some just grab ingredients, taste what they're making and revise it as they go along. That's the way I paint. But I know I've got a long way to go. And you're never going to get entirely to where you want to go.

- Rory Jackson

- "Weaving Us Into Life"

SD: Where do you want to go as an artist?

RJ: I want to be fluid and fresh in all my work. I want to be able to describe with paint the time of day and the light you can't capture in words or photos.

SD: Do you work from photos? And please tell us your method of painting.

RJ: A lot of the work I do in the studio is from photos. But I much prefer working outside. The sound of the birds, the waves, people talking, I find really soothing. But it's hard to paint a large-scale piece from start to finish outside.

It takes me about two weeks to complete a painting. Some are easier, especially the ones with a lot of open space that's sand or sky. But then you get into the color of a kid's dress, and you're there for some time.

I start by drawing or underpainting with sienna wash, then block in my colors, let it sit for a couple of days, then start working on it with linseed oil mixed with paint.

I feel like every line is malleable. And if you allow that to be true, you're never stuck; you're working from the outside in and the inside out.

SD: Outside in? Inside out?

RJ: You want to express your truth from your inner artist. At the same time, you have to paint with a view to an audience that will support you.

SD: Your figures are as well executed as the places where they're set. Do you ever do portrait painting?

RJ: I've done a bunch of studies. It's interesting to pick out and put across the qualities in a face. But I don't do full portraits because much of that is commission work, and it feels to me like being put in a box.

SD: How did you come to be so involved with Ghana? What made you want to start a school there?

RJ: After that first trip, I went back a couple of times after high school. I built a little mud house in the Volta Region [in eastern Ghana], near a very poor community. I'd ride my bike around, and the local kids would hang out with me. I helped them with homework, made sure they would go to school. I was kind of a big brother to about a dozen kids.

Another time, I did a walkabout along the coast for a couple of weeks and came upon Cape Three Points. It was a piece of paradise in my eyes. I built a house there, and the same thing happened, with kids hanging out at my place. I wondered what I could do to help them pursue their dreams, or at least find work. I asked community elders what would be the most beneficial thing, and they said a high school, trade oriented, would be the best.

[The 20 or so students who attend Trinity Yard School at any given time receive a free secondary education with a focus on English language skills, reading comprehension and math. They also take part in a variety of vocational workshops, including one that teaches traditional kente weaving. The students receive career counseling, with the school helping place them in senior high schools, vocational institutions and apprenticeship programs of their choice.]

SD: It's been a pretty brutal winter in Vermont. Are you tempted to live full time in Ghana?

RJ: If I was in Ghana full time, I would miss my family in Vermont, miss seeing my mom, miss seeing my brother's kids grow up. I have a very close relationship with my mother. I see her every day.

Our kids are part of the community in Lincoln. When we go back to Ghana, they're treated like the princes of Cape Three Points. It would be harder for my kids to have equal relationships with their peers there.

But I do love Ghana, man. There's this kind of electricity in the air — you can almost touch the energy. I love the culture, the music, and I met a woman there who I fell in love with.

So the plan is to live in Vermont and go back to Ghana part of the time. The aim is to stay free and not acquire too many things. I feel like I've acquired too many things in Vermont.

SD: How does your wife like living in Lincoln?

RJ: She likes it for the most part. She likes that the kids are happy and doing well in school. But she doesn't like the cold.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.