- Courtesy

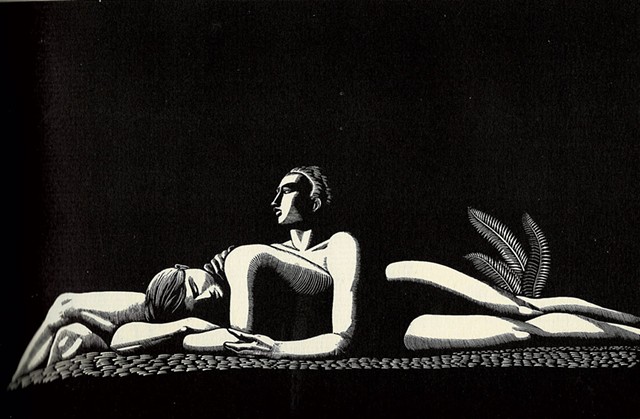

- "The Lovers"

Rockwell Kent's spare, iconic 1928 wood engraving "Flame," now on view in the University of Vermont's Fleming Museum of Art, can have the effect of engraving itself on the viewer's mind. A nude on his back, one bent knee in the air and the other folded over a ledge in the lower foreground, reaches a yearning hand to the night sky. The vertical gesture is backlit, so to speak, by a single flame, sinuous and towering, that emanates remarkably fine lines of light for the medium.

Kent (1882-1971), an admired American landscape painter in his time, found public fame and commercial success with his wood engravings and lithographs, which he began creating in 1919. The Fleming now hosts a selection of these mainly black-and-white works, titled "Rockwell Kent: Prints From the Ralf C. Nemec Collection," that range from Kent's first wood engraving to a 1948 lithograph.

Nemec, of Deer Park, N.Y., chose the traveling show's 49 works from his collection, the world's largest, to illustrate the artist's breadth of work, said the collector by phone.

- Courtesy

- "Flame"

In addition, the exhibit includes a reproduction of a pen-and-ink poster by Kent from the Fleming's archive, which the artist made to look like a wood engraving; a selection of prints by Vermont printmakers of the era including Ronald Slayton; Works Progress Administration-sponsored instruction boxes on how to make wood cuts, wood engravings and lithographs; and illustrated books from UVM's Special Collections, including special editions of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, Voltaire's Candide and Kent's own books, all illustrated by him.

Alice Boone, Fleming curator of education and public programs, wrote the numerous panels. Part of the enjoyment of the show is reading about Kent's work as assessed by Boone, who has a doctorate in English and comparative literature and curated an exhibition at the New York Public Library on Candide in 2010.

Kent, born in Tarrytown, N.Y., trained with the Art Students League of New York during college summers and eventually left an architecture degree program to attend the New York School of Art. There, he studied under William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri; Edward Hopper and George Bellows were among his classmates.

His sensibility was decidedly leftist. Kent joined the Socialist Party in 1904 at age 22, supported workers' causes and was later blacklisted as an alleged communist by senator Joseph McCarthy. He took up wood engraving and other reproducible image making for the democratic potential these mediums offered to make art accessible. In this, Kent was of his time; all over the world, in the 1910s and '20s, revolutionary artists were turning to printmaking to reach the masses, from Germans protesting war to Latin Americans celebrating labor to Russian avant-gardists experimenting with constructivist prints.

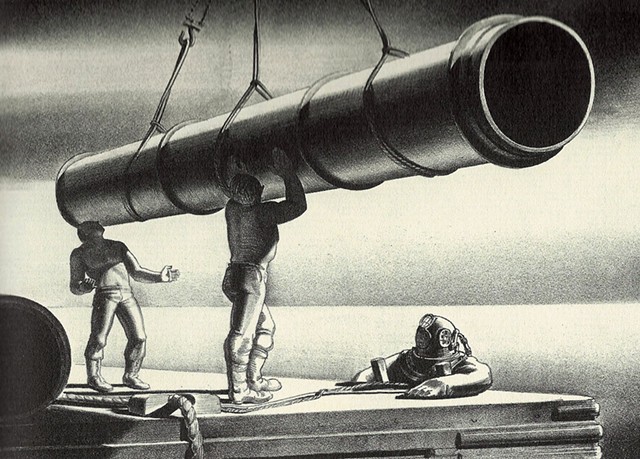

- Courtesy

- "Big Inch"

Yet Kent's art often features solitary Übermensch-type figures conquering the wilderness by individual effort alone. (He read widely, including Friedrich Nietzsche and Henry David Thoreau.) For the cover of the July 1937 issue of the leftist magazine New Masses, Kent created "Workers of the World Unite!" — a strikingly dynamic engraving showing a barefoot worker wielding a shovel against the encroaching flames and swords of management. But, as Boone points out in the panel, "Where are his union members, his comrades?"

A more representative image of the era, included in the exhibit, is "The Breadline" (1931) by Vermonter Clare Leighton. The wood engraving shows a packed line of hungry workers extending into the distance. Masses of people were not Kent's thing; even his cover of a 1936 report on the Vermont Marble Company workers' strike centers on a single, sturdy but worried-looking mother holding an infant and leading three more children — an image that echoes the style of Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco.

After visiting the artists' colony on Monhegan Island, Maine, in 1905, Kent began traveling to remote places for extended stays, including Newfoundland, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego and Greenland — sometimes with family members. (He was married three times.)

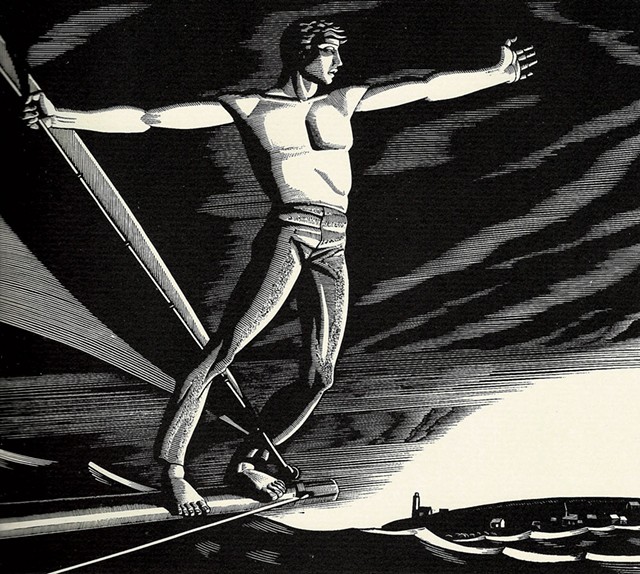

- Courtesy

- "Home Port"

He transformed the illustrated travel diaries he kept into adventure memoirs. In N by E, his 1930 account of the first Greenland trip, Kent included three wood engravings titled "Bowsprit," "Starlight" and "Home Port." These were from a series of 12 advertisements he made for the American Car and Foundry Company to promote its new line of yachts. As illustrations of his own travel, they are merely suggestive, showing a single, muscular nude hugging a bowsprit in starlight or balanced on it wearing only thin pants. Boone asks reasonably in the panel, "Can one be naked outdoors on the North Sea?"

More pertinent to his travels are Kent's stylized lithograph depictions of Inuit community members from his 1931 to '32 trip, published in 1962 as Greenland Journal. With their broad torsos and foreshortened legs that come to a knifelike point, the figures in "Greenland Hunter" and "Greenland Courtship," both from 1933, resemble their weaponry.

Between trips, Kent created magazine illustrations, industry advertisements, Christmas cards, book plates and more. (He produced some at his Arlington, Vt., farm, his home base from 1919 to 1925.) Some of his wood engravings combine commercial techniques with leftist messages. "Eternal Vigilance Is the Price of Liberty," a 1945 lithograph of a muscled man in pants shouting to alert others to a fire, includes its own title in the image, like an advertising motto. The saying has been linked to preserving democracy for the many over the few.

Likewise, Kent's industry advertisements take on the qualities of his art. "Big Inch," a 1941 lithograph, was part of a series commissioned by the U.S. Pipe & Foundry Company in New Jersey. In it, a vast emptiness similar to Kent's stark wilderness settings becomes the background to a scene in which two powerful-looking men, each working alone, manipulate a huge, suspended section of pipe.

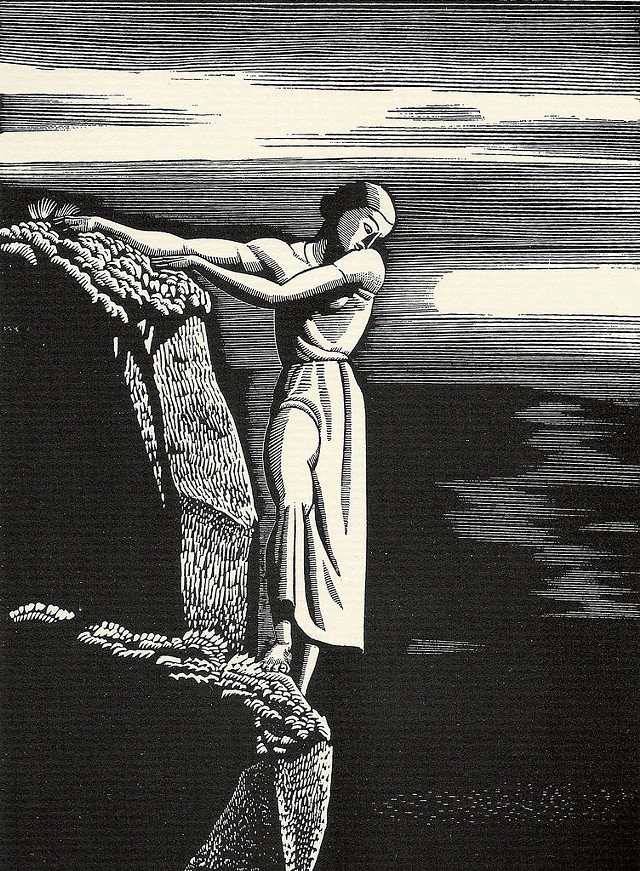

- Courtesy

- "Girl on Cliff"

"I find it so fascinating to think about an artist who had strong leftist political sensibilities making illustrations for U.S. Steel the same year as the strike," Boone commented by phone. Asked whether that presented a contradiction, she said, "I think that any good Marxist will tell you that contradiction is what drives things forward. That churn of opposites seemed to be really generative of his creativity."

After the McCarthy hearings, Kent's passport was revoked in 1950 — he had to bring his case to the U.S. Supreme Court to get it back — and his work began to fall out of favor. He ultimately donated hundreds of his works to the Soviet Union, which awarded him the International Lenin Peace Prize in 1967.

"He was, for all intents and purposes, canceled," said Nemec by phone. "But he's back." The collector, who counts a line of china decorated with Kent's Moby-Dick illustrations among his holdings, said Kent prints now sell for between $2,000 and $10,000.

Kent's work has deeply influenced the field of graphic design, Boone said, and generated a whole group of "Rockwell Kent superfans" that she learned of when they visited the exhibition.

"Whether people know Rockwell Kent or they're just getting introduced," Nemec said, "they're always impressed."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.