- Courtesy

- Robert D. Putnam in Join or Die

In 2000, Harvard University professor Robert D. Putnam published Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Its roughly 500 pages charted the unraveling of American social and civic groups and warned of the threat that posed to personal and civic health.

Pete Davis thought the book was a downer when he studied it as a student in Putnam's "Community in America" class in 2010. He and his peers were feeling good about how things were going in the country, while Putnam was pointing out that fewer Americans were going to church, joining the PTA, singing in choral societies and having picnics. They were bowling, but not in leagues. The resulting decline in so-called "social capital," Putnam said, posed a threat to democracy.

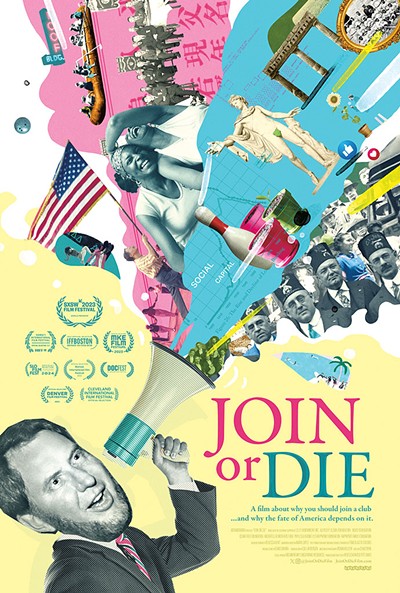

Ten years later, as the trend continued, Davis, a writer and cofounder of the Washington, D.C.-based Democracy Policy Network, realized that Putnam was right to be concerned. Democracy was in trouble, and Davis decided it was time to reconnect with his old professor. The result is the 2023 award-winning documentary Join or Die, which comes to Burlington's Fletcher Free Library on Friday, October 4. Putnam will participate in a post-screening discussion.

Davis and his sister, Rebecca Davis, a former producer for NBC News and Vox's Netflix show "Explained," codirected and coproduced the film. Join or Die features interviews with former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg and U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and spotlights six community groups across the country. Chad Ervin, co-owner of Montpelier's Well Told Films, edited the documentary.

Putnam, 83, figures he has spoken to more than 300,000 Americans in the past 25 years, a one-man prophet trying to redirect his country. The film takes his message to a wider audience — he now gets five to 10 speaking invitations a day — "so I'm hopeful," he said. Putnam talked with Seven Days from the study of his Jaffrey, N.H., home, looking across his pond toward Mount Monadnock.

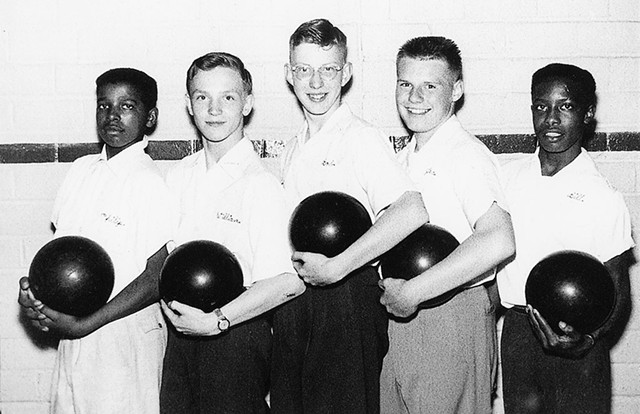

- Courtesy

- Robert D. Putnam (center) with his school bowling team

You're credited with creating the term "social capital." What is it, and how does it affect individuals and society?

I did not actually invent the term "social capital," but I guess it would be fair to say I popularized it. The core idea is super simple: It is that social networks have value. They have value to the people who are in the networks. If you're in a network, that has a powerful effect on your health. Your chances of dying over the next year are cut in half by joining one group. So it's a very powerful effect.

Also, networks have externalities — that's the economics jargon for it — their effect on bystanders. If you happen to be worried about the quality of schools in your community, you could pay teachers more, get higher-quality teachers, or you could get more parents involved in the school. I'm not opposed to paying teachers more. My wife was a public school teacher, so I had a vested interest in paying teachers more, and I'm strongly in favor of that. But in fact, getting parents involved in the schools will have a better effect on the performance of kids in the school — and not just for their kids, but for other people's kids. It's a quite remarkable effect.

The same thing is true for crime. If you're worried about crime in your neighborhood, you might say, "Let's put 10 percent more cops on the beat" or "Let's have 10 percent of the people in your neighborhood know one another's first name."

Social capital also creates better government, correct?

Absolutely. Social capital is the greatest thing since sliced bread. It's just utterly amazing how many things are affected by these social networks, and one of them, the discovery of the fact that social capital is good for democratic government, is actually the opening story in the film. And I don't want to upstage the whole film, except to say I discovered this in Italy.

What are the most interesting clubs you've heard of, and can you explain how they've been effective in building social capital?

I'm going to go on a little riff here. Socially isolated, lonely young men are really dangerous. I ask you to think over how many school shootings [there are]. Not every shooting is done by a lonely young man, but a huge proportion of them are. Now take a trip with me back 125 years. It's the beginning of the 20th century. And exactly the same thing was true then. And the name for it was the Boy Problem.

What was the Boy Problem? It wasn't school shootings, because guns were not as available then. But it was young, isolated boys who were getting in trouble and committing crimes. And then, within five years, virtually all of the major youth-serving organizations in America were invented: the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts and the Camp Fire Girls and the Boys Clubs of America and Girls Clubs and Big Brothers Big Sisters. Why? They recognized they had a problem, and their solution to the problem was, Let's create some type of clubs for these kids. Astonishingly, that fixed the problem.

Let's look at Boy Scouts. I'm not saying that Boy Scouts are the right solution for the future, but they sure were the right solution for the 20th century. So how did it work? Well, first of all, it was fun. You went hiking, and you camped in the woods, and you earned a merit badge for knowing different birds. But at the same time, it was character building.

You refer to two kinds of social capital: bonding social capital, the connections between people who are alike; and bridging social capital, which connects people who are not alike. That's the harder one, and it seems to be the one that our polarized country needs the most.

Correct.

How do we do that?

- Courtesy

- Join or Die poster

It's really hard, and it's hard right now in the middle of this election. I'm very much opposed to Trump, and I actually find it hard to imagine sitting down enjoying an evening with a bunch of Trump folks, but I want to tell you a story about what happened here at our house in Jaffrey yesterday afternoon. A bunch of the neighbors got together because one of the people in the group was about to move away. And we were standing around talking. We were talking about whether this was going to be a good [foliage] season. And we were talking about how we were going to get the driveways here plowed because we're off in a little cul-de-sac, so we have to arrange for our own snowplows. And we even talked a little bit about politics. It turns out that not all of us agree.

That was bridging social capital. Here we all were connecting. We're all alike in the sense that we all live in the midst of this beautiful little setting here in southern New Hampshire, but we were different in other respects. I came away understanding a little bit more why this one guy, who happens to be a local basketball coach, likes Trump. He didn't convince me to like Trump, but I did understand him a little better.

How did that work? Well, it worked because, although we were bridging politically, we were bonding on a lot of other things. The way to build bridging social capital among groups who don't have a lot in common is to find something they can bond over. Once you've done that, you can stand in the shoes of the other person just a little bit.

Tell me how your wife, Rosemary Putnam, became the costar of this film.

Well, she's in the movie because the movie is sort of the story of my life. We met when we were probably 18. We were in college together. We happened to be in the same poli-sci class in the fall of 1960. That was the year in which John Kennedy was running against Richard Nixon. I was a moderate Republican. Rosemary was a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat. But nevertheless, we started hanging out. This is the bridging/bonding thing again.

Our very first date was what was then called Sadie Hawkins Day. It was then very rare that a woman could invite somebody out. Rosemary asked me out for the date. And what was our date? Our date was going to a John Kennedy rally. That was kind of: In your face, Putnam. Well, of course, turnabout was fair play. The next week, I took her to a Nixon rally. And before the election, she'd already convinced me to be a Democrat, and I still am.

We were at Swarthmore College, just outside of Philadelphia. I said, "It's not that far to Washington. Let's go down to the inauguration." We stood in the crowd, at the back of the crowd, and we heard [president Kennedy] say, with our own ears, "Ask not what your country can do [for you]. Ask what you can do for your country." And that was a life-changing moment for me.

This is one powerful lady we're talking about. In the first four months of our knowing [each other], she's changed my career and she's changed my politics. I talk about social capital, but she does social capital. It was not accidental that Rosemary's the person who arranged for us to host the neighborhood party yesterday. Even after she retired from special education, she spent a lot of time tutoring. She's a born social capitalist, and I just write about it.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.