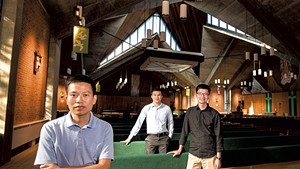

- Matthew Thorsen

- Kathleen Rivers Libby

Five former residents of St. Joseph's Orphanage chatted nervously in the Burlington College lounge on Friday afternoon, waiting for a tour of what was once their home.

Debi Gevry-Ellsworth, 57, lived in the orphanage run by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington from 1964 to 1974. She drove from Connecticut to see the building one last time before renovations alter it forever.

Sheila Billow Cardwell, an elegantly dressed 60-year-old woman, had traveled the farthest — from Salt Lake City, Utah — to get a final glimpse of the place. She lived in the orphanage from 5 to 14, when she aged out. "My mother was 29 years old with her 10th child, and my father was quite a bit older and in the veterans' hospital," she explained. "And back then ... they used to take the children away from the parents if they couldn't afford them."

The other three women live in the Burlington area, so they confront their memories every time they drive down North Avenue past the looming stone building.

The aging former residents leaned against the wall and awkwardly made conversation. "Were we here at the same time?" they asked each other. "What was your number?"

Cardwell, who lived at the orphanage from 1960 until 1968, explained: "When people say 'What was your name?' I say, 'What was your number?' because that was the way we classified ourselves. We lined up by numbers, we went to bed by numbers, everything was by numbers."

Although most of them overlapped at the orphanage at least for a year or two, they had few, if any, memories of each other. Life there was regimented, and daily activities were segregated by age. But as they looked around the room together, they developed an easy familiarity.

"This was the nuns' area," Gevry-Ellsworth explained.

"Around the corner was first grade, and second, third," Cardwell added. "It's all the same."

Constructed in the late 19th century, the orphanage provided foster care to Vermont children for decades. Some were orphans, but many, like all of the women on the tour, had parents who for some reason couldn't take care of them. Many families relied upon the orphanage for help when they fell on hard times.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Debi Gevry-Ellsworth (left) and Sheila Billow Cardwell (center) listening to Valerie Clairmont Smith

St. Joseph's closed in 1974 and became the administrative offices for the diocese. But the orphanage came back to haunt church officials in 1993, when former resident Joey Barquin came forward to say he had been abused by his caretakers there. Barquin's case opened the floodgates, and more than 100 other orphans came forward with similar allegations. The church offered dozens of claimants $5,000 each for therapy costs if he or she agreed not to sue.

Later, in the early 2000s, the diocese found itself back in the spotlight for a series of sex-abuse scandals involving priests around the state, and it wound up paying out more than $20 million to settle claims. That's what prompted the cash-strapped Catholics to sell their headquarters to Burlington College in 2010. The college renovated the diocese offices, located in a 1940s-era addition, but left the original 19th-century building mostly untouched.

Last winter, Burlington College announced it was selling the orphanage to developer Eric Farrell, who has also purchased much of the surrounding acreage. Farrell plans to build housing on the property and recently got permission to convert the orphanage into apartments.

When former resident Katelin Hoffman, now 58, heard about the orphanage project, she set out to arrange one final tour. Hoffman believes that it's critical for former residents to speak out and share their stories. As the manager of the Children of St. Joseph's Orphanage Facebook page, she urged its 94 followers to come, posting that she wanted to "reach as many people as possible who may need to ... tour, do what they need to, and let it go. Some did fine there. For them it will be different, but still important. Some can't get near the place yet. Those of us who can go, I hope we can make it as powerful as we need it to be."

Her repeated posts and pleas drew together this group of 10 people — five female former residents, three of their husbands and two relatives of deceased orphanage occupants.

Coralee Holm, the Burlington College dean of operations and advancement, arrived to lead the tour, which started in the renovated portion of the building the college uses for classrooms and offices. Though the space is modernized, every inch of the building — even a quick glimpse of the original wood floors — elicited a torrent of memories. The women interrupted each other with stories about melting floor wax on the radiator and being small enough to ride the giant floor buffer across the room.

- Matthew Thorsen

But their chatter ended when they entered the Burlington College library in what used to be the orphanage's gymnasium. Although it's now a cheerful, sunny room lined with books, Gevry-Ellsworth announced loudly, "It really gives you the creeps."

Cardwell gestured toward the tiny raised stage and explained quietly that children who wet their beds were forced to stand there in only a sheet, while the other children taunted them. She recalled a song used to tease a redheaded little boy, Leroy, who was a chronic bedwetter.

"Leroy, Leroy wet the bed," she whispered. "Wipe it up with gingerbread."

The women chattered as they moved quickly through the renovated portion of the building, trying to remember what the rooms had been used for and sharing anecdotes.

Valerie Clairmont Smith, 57, from Waterbury Center, remembered running away to JCPenney and spraying her hair gold; Gevry-Ellsworth described taking off her girly shirt and sneaking over to the boys' side of the playground because they had a cooler slide. Both women remembered filling their hands with lilies of the valley before they had to pray, so they could smell the flowers during the endless rituals.

"I'm filled with anxiety right now," Gevry-Ellsworth said softly, as she waited for the elevator to the girls' wing, where they all once lived.

The group grew quiet when they entered the familiar setting, which remains mostly unchanged since the orphanage closed. As they walked through the rooms filled with dust and falling plaster, the women reminisced about the nuns who, they said, would pull children out of their beds at night and beat them; about the kind seamstress who took care of them; about making up sins during confession, so they had something to tell the priest.

They walked into a small room with a large wooden table — the "sewing room," somebody announced.

"You see the numbers!" Gevry-Ellsworth exclaimed, pointing to the row of cubbies where their clean clothes used to be placed. Cardwell ran her hands along the wood, brushing aside the dust, until she found her number.

"This was April, and this was Cheryl," she said, moving her fingers from cubby to cubby.

The entourage moved across the hall to a pink-tile-lined bathroom filled with rows of tiny sinks. "That's the bathroom I remember washing my underwear and socks in every night!" Smith announced. Cardwell leaned against the window and grinned, "This is where you could see the boys ... You could meet at the windows," she said.

Hoffman placed a piece of paper with a poem against the window and explained that she wrote it one night in the orphanage when she was frightened and snuck out of bed to stand here and look at the moon. In the poem she asks the moon to "please help me to be like you are, to be able to see but not ... feel what's happening."

The tour continued up into the attic and then down a few floors to the chapel. The women walked into the old confessional booths, peeking through the screen that had separated penitents and priest. Smith wrinkled her nose. "It smells the same," she said, then asked the group: "What does it smell like?"

"Orphanage," Gevry-Ellsworth answered, and they all laughed.

At the end of the tour, they gathered in the main entryway and shared memories — some of them visceral.

Gevry-Ellsworth described sitting in the front parlor on weekends, swinging her feet and waiting for her father to arrive, dreading the moment when a nun would announce, "He's not coming."

"He would never show up. He would just leave us there," she remarked sadly. But even when he did come, the visits were all too brief, and she would have to trudge back through the foyer Sunday evening and walk to the right, while her brother went left. Once they were back at St. Joseph's, they weren't allowed to speak to each other.

Smith had different memories of that foyer. When new babies were dropped off, she said, the nuns would grab whatever kids were around and designate them "godparents."

"I had so many godchildren!" she laughed.

"I think this place maybe helped some families," Kathleen Rivers Libby, 73, from South Burlington, said tentatively. A tall, graceful woman with soft curls, Libby lived in the orphanage for a year in 1949, after her mother got sick. "The six of us had to go somewhere," she continued. Her father reluctantly placed the four older kids in the orphanage, while he sent the younger two to family members.

"I'm glad they're not tearing it down, you know?" Cardwell added.

"There should be some kind of historical landmark," someone else suggested.

Gevry-Ellsworth broke into the conversation.

"I have a lot of residual things," she announced. "I'm petrified of the dark. I have a really hard time in the dark, and if somebody calls me mean—" she broke off, beginning to cry.

Her husband, Jim, took her in his arms and explained: "They used to call her 'evil child.'"

"I would always think I was mean," Gevry-Ellsworth continued, "and evil. And I had a really hard time working through that, because the nuns wore you down with that. 'You're going to hell.' 'You're mean and evil.' But we were just kids. Just kids being kids."

The group fell silent.

"You won," her husband told her. Everyone nodded. He repeated, "You won."

Disclosure: Sarah Yahm works part time as an instructor at Burlington College.

Comments (14)

Showing 1-14 of 14

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.