One of my work email folders is labeled "Lives." It's a bit of a misnomer, since the folder pertains solely to people who have died.

"Lives" is internal Seven Days shorthand for "Life Stories," our annual collection of profiles of Vermonters who died that year. We've been running the year-end package since we began publishing obituaries in 2014. Deputy publisher Cathy Resmer conceived and spearheaded "Life Stories" to celebrate Vermonters whose lives were interesting or extraordinary but whose names might not be known to readers. It's now also an ongoing series that I oversee, with the invaluable help of staff writer Sally Pollak.

So I collect obituaries. Lots of them.

Combing through obits all year can be a depressing exercise. It would take a pretty calloused soul not to feel something when reading about the lives of the recently deceased in the words of their loved ones.

But I also tend to find obits life-affirming. They can be funny and illuminating and remind us of the many different kinds of people in the world and the endless ways to live a life. A good obit can inspire the reader to feel admiration and to wish they'd known the deceased.

"Life Stories" profiles aim to make a similar connection. We generally avoid Vermonters whose lives (or deaths) were widely covered in the media. And we strive for a range of ages and ethnic, economic and geographic backgrounds. Otherwise, we simply look for people whose stories intrigue, inspire or touch us for one reason or another.

We hope you find inspiration in the following profiles of Vermonters who died in 2022. Our deepest gratitude goes to their families and friends for sharing their life stories.

— Dan Bolles

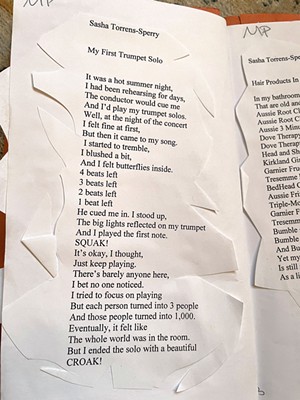

Sasha Torrens-Sperry

July 16, 1993-July 24, 2022

- Courtesy

- Sasha Torrens Sperry and her mom, Abigail

Sasha Torrens-Sperry was in the sixth grade when she performed her first stage solo, during a camp for young musicians at the Flynn in Burlington. She later recalled the experience in a poem, "My First Trumpet Solo."

"I felt fine at first," she wrote of that seminal moment. "But then it came to my song. / I started to tremble, / I blushed a bit, / And I felt butterflies inside."

Her mother, Abigail Sperry, rereads the poem often.

"I was looking through things after she passed away, and I found it," she said as she sat at a coffee shop in downtown Burlington, an early winter snow falling outside the window. "I love it for so many reasons, but it showed that she had stage fright, which is so incredible with someone who's that talented."

"4 beats left," Sasha's poem counts down. "3 beats left / 2 beats left / 1 beat left."

Sasha, multi-instrumentalist, vocalist, producer and teacher, died in New York City on July 24, after a long battle with addiction. She was 29.

She was born in New York City in 1993 but moved with her family to South Burlington later that year. As a child, her musical talents were unmistakable. Both her mother and her father, Alejandro Torrens, were musicians, so it surprised no one to see the young girl sitting comfortably at the piano. But it was her ability to listen that indicated how skilled a musician Sasha would become.

"Her ear was incredible," said musician Francesca Blanchard, who went to Champlain Valley Union High School with Sasha. The two would become collaborators when Sasha joined Blanchard's band and played on the indie pop singer's debut album, Deux Visions.

"She could harmonize on everything," Blanchard said. "She was a melodic musical genius. Some people have it, and she's one of them."

- Courtesy

- A poem by Sasha

Abigail recalled Sasha as a toddler, hearing the theme song to the Nickelodeon cartoon "Rugrats." She bolted straight for the piano and started to work out the notes to the song. She would do the same for the music she heard in video games, even figuring out how to reproduce on the piano the demo songs built into Abigail's keyboards.

"She was that type of kid," Abigail said. "She loved going for challenges. She could be so fearless sometimes."

Sasha dabbled in sports and enjoyed video games but in the end always came back to music. By the sixth grade, she had joined the Vermont Youth Orchestra, excelling on piano and trumpet. By the time she performed her first solo, her musical ability was clear.

"He cued me in," Sasha wrote in her poem about her solo. "I stood up, / The big lights reflected on my trumpet / And I played the first note. / SQUAK!"

Despite her stage fright, Sasha's talents were often on display in school plays, including a 2009 production of The Pirates of Penzance. One reader of the Williston Observer wrote in after seeing the comic operetta to laud Sasha's performance as the nursemaid-turned-pirate Ruth and to describe her "incredible singing voice" in a performance that was "some of the finest acting in the show."

"She was also just absolutely hilarious," Blanchard pointed out. "She was a total goofball, a ridiculous girl in the very best way."

Abigail often thinks of her daughter's humor, as well.

"Sometimes, in the harder moments of coping with her loss, I've thought about how funny she could be, how dark and sarcastic. When we were dealing with her ashes, I asked myself, 'What would Sasha say about this all?' Because I knew she would have had the perfect, hilarious thing to say about it."

After high school, Sasha attended Berklee College of Music in Boston and earned a degree in electronic production. Going from the relatively small music scene of Vermont to Berklee, a school stocked with talented musicians, caused a strain on her. She confessed to her mother how overwhelmed she was sometimes.

"Musicians don't seem to have a lot of resources when they're struggling," Abigail said.

"Personal demons dictate how we are in our lives," Blanchard added. "But even with those fears and dealing with the root of her addiction, Sasha was always so brave. I mean, she went from Berklee to New York City, and, as a musician, that is such an intense grind. You really have to back yourself."

Sasha moved to the city in 2017 and set out to create her own music. Working under the moniker Hunnydrips, the classically trained musician moved into hip-hop and electronic music. Her Soundcloud page is full of hazy, chilled-out beats and inventive, atmospheric remixes.

"She always wanted to produce her own music," Sasha's cousin Edelweiss Nicole Lavandier said by phone from her home in New York City. "She really wanted her own studio in the city, too, somewhere we could play music together."

Although they never got that studio, the two lived together for a time. They both took jobs as teachers at the Williamsburg School of Music in Brooklyn, where Sasha taught kids to sing and play piano and trumpet.

"She was so good at it," Edelweiss said. "The kids just adored her. I could hear her voice ringing out, showing them a G minor or correcting their pitch."

Though Abigail said Sasha was never the "babysitter type," something about interacting with kids through music seemed to light her up and bring out her best.

"If you ask anyone who had a lesson with her, she made them feel confident," said Abigail, who took voice lessons with her daughter. "She was so great at explaining concepts and keeping them simple at the same time."

Edelweiss said there were happy times for her cousin in the city, but she also saw Sasha's difficulties up close.

"Sasha got pretty bad at one point," Edelweiss said, recalling her cousin's struggles with drugs and alcohol. "I've been around addicts, so I knew what she was going through and how hard that fight really is. I started to prepare myself for that call — I was literally expecting it."

- Courtesy

- Sasha as a baby

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic left Sasha feeling both isolated and under pressure to produce more work. Though she continued making music as Hunnydrips, addiction and anxiety often hampered her abilities. She struggled with the expectation to make good on her potential and find some semblance of work-life balance.

"You make money versus making your art, and when one gets in the way of the other, you feel like you're not doing enough," Blanchard said. "That's the classic trope, the curse of the creative."

For a time, Sasha grew healthier, going through rehab and getting sober. Edelweiss was relieved to see her cousin bouncing back but worried that too much damage had already been done.

"She came over for dinner one night and sat at my piano," Edelweiss recalled. "She was sober, and she was smiling, but it's like I could see this hole within her, this place she couldn't quite fill up. There was just such sadness in her sometimes."

Now that she's gone, Abigail finds comfort in playing her daughter's music on the piano. A musician friend of Sasha's took one of her compositions, transcribed it and gave it to Abigail after the memorial service. Every day, she lights a candle and plays the song, a sort of running conversation with her daughter.

"There are so many layers in her music," Abigail said. "You can hear these little bits of her personality shine through, her classical training. Something that sounds like Ravel will pop up, and I'll smile because I know that's her."

She paused, lifting the coffee cup to her lips before sharing one last thought.

"I do wish she left us more of her music."

— Chris Farnsworth

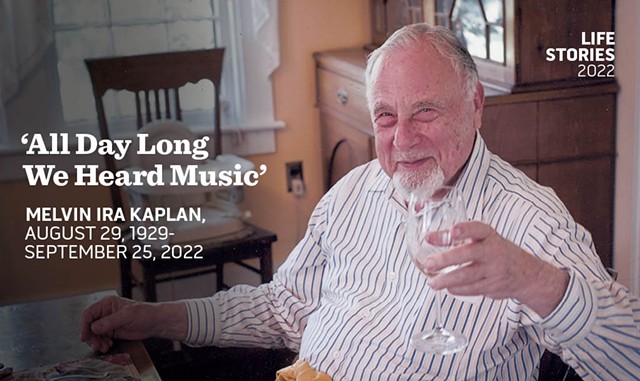

Melvin Ira Kaplan

August 29, 1929-September 25, 2022

- Courtesy Of The Kaplan Family

- Mel Kaplan

Whenever Melvin Kaplan met people — and he met many in his decades of world travel as a professional musician — it was never long before they would hear him say, "Now, that reminds me of a story..."

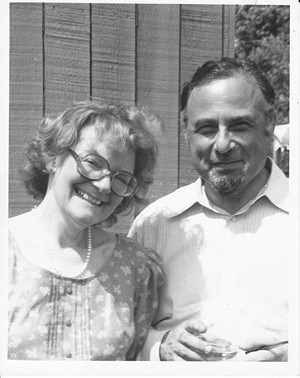

At heart, Mel was an entertainer. Friends and family remember him for his prolific repertoire of stories and jokes, many of which were too off-color for them to repeat to a reporter. Mel also loved entertaining people at the Charlotte home he shared with Ynez, his wife of 65 years. He was a bon vivant who collected fine wines and relished exquisite meals, many made with ingredients he grew in his garden and greenhouse. Ynez often prepared dishes from recipes she'd discovered in their travels.

But first and foremost, Mel was a world-class oboist with a passion for classical music, whether performed by him or in concerts he organized. Trained in music from age 16 at New York City's Juilliard School, where he served on the faculty for 30 years, Mel performed in concert halls around the world, often sharing the stage with Ynez, a Yale University-trained violist.

Years later, Mel founded an artist management company that served elite musicians. With an encyclopedic knowledge of classical music and a knack for putting together colorful programs, Mel, as cofounder and artistic director of the Vermont Mozart Festival, brought some of those world-caliber concerts to Vermonters.

- Courtesy Of The Kaplan Family

- Mel with his wife, Ynez

"There's something that Mel often said," recalled his longtime colleague and friend John Hammer, who served as director of the Vermont Mozart Festival for more than five years. "'It's amazing. They pay me to do the most wonderful thing in the world, which is to play music.'"

Mel was born on August 29, 1929, in the Bronx, N.Y., the second of three sons of Edna and Barnet Kaplan. His parents weren't musicians themselves, but they played classical music for the boys when they were still in the womb.

While Mel was a boy, his mother would play WQXR, a classical radio station, recalled Burton Kaplan, Mel's younger brother.

Soon enough, Mel and his older brother Harvey were playing instruments. "When I was born, I could hear [my older brother] Harvey playing Mendelssohn violin concertos at age 12, and Melvin was playing Mozart piano sonatas at 7," Burton said. "So all day long we heard music."

At 12, Mel was accepted into the High School of Music & Art in Manhattan and was required to take up an orchestral instrument, according to his brother. Mel chose the oboe, one of the most difficult woodwind instruments.

But he was adept with his hands. Burton recalled how Mel loved making his own oboe reeds.

Though Mel loved to perform, Burton said, he hated to practice. "In that sense, he was very rebellious."

Mel rebelled in another way — against his parents' Orthodox Jewish faith. An avowed atheist his entire life, Mel was "rather opinionated and headstrong" in that regard and others, Burton said, and he went on to marry outside the religion, twice.

Mel's first wife was Teresa DiDario, a Juilliard-trained bassoonist. They had two children together, Eric and Karen. But the couple separated when the children were very young.

Karen, who was only an infant when her father left home, recalled seeing a newspaper clipping from when her parents were married; it featured a photo of Mel with another woman. Though its caption read, "Mel Kaplan and his wife," in fact, the picture was of Ynez. Karen's mother, who died in 2015, kept that clipping her whole life.

"I guess a broken heart never gets mended," Karen said wistfully.

- Courtesy Of The Kaplan Family

- Clockwise from top left: Mel Kaplan, Liz Metcalfe, Alex Kougel and Ynez Kaplan

But Karen and Eric, who later moved to Italy with their mother, stayed in touch with their father. Each summer, they flew to New York City and spent a month with Mel, either vacationing at Ynez's family home in rural Connecticut or at Bennington College, where Mel often ran a summer music program. Sometimes, Karen babysat for Mel and Ynez's children, Jonathan and Christina. Despite the initial awkwardness of their family arrangement, Karen said, Ynez was always very loving toward her.

Mel's passion for contemporary classical music led him to create the New Art Wind Quintet and then, in 1957, the New York Chamber Soloists. It was through the latter group, which Mel managed and performed with until 2015, that he and Ynez traveled the world extensively, performing concerts throughout Europe, Australia, New Zealand and South America.

"He could land in Buenos Ares and know half the musicians there," Hammer recalled.

In 1961, with his extensive network of musical connections, Mel founded Melvin Kaplan, Inc. — now MKI Artists — a music management company. His firm represented musicians from cities including Berlin and Leipzig, Germany; Paris; Prague; Zurich; and Tel Aviv, Israel. In 1976, Mel moved his family from New York City to Charlotte and relocated his business to downtown Burlington, where it's still headquartered.

Mel's son Jonathan recalled a typical workday for his father. Mel would go to his office on College Street until about noon. He'd then come home, change into his gardening clothes, and spend the afternoon working in his greenhouse or garden, raising flowers and vegetables year-round.

"He always planted peas in March," Jonathan said. "And he grew artichokes in Vermont. I don't know anyone else who does that."

In their later years, Mel and Ynez moved to Randolph to be closer to Jonathan. While he was helping them downsize, Jonathan discovered his father's gardening notebooks. Written in them, like orchestral arrangements, were detailed plans for what he would plant that season.

In 1974, Mel and William Metcalfe cofounded the Vermont Mozart Festival, which brought acclaimed musicians to gorgeous outdoor venues such as Shelburne Farms, the Trapp Family Lodge in Stowe and the Basin Harbor Club in Vergennes. Over the festival's 37-year run, thousands of Vermonters enjoyed these summer performances. Hammer said that Mel, as the artistic director, never stopped dreaming up new and interesting concerts.

"He used to put together programs like no one else could," Hammer said. He'd call and suggest, say, doing a program on the "Three Bs" — Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms and Johann Sebastian Bach — then decorate the programs with bees.

"Mel had a twinkle in his eye, especially when he had an idea he wanted to share," Hammer added. "And it always worked out. That's the beauty of Mel."

Though Mel wasn't known for listening to or appreciating other musical genres — "I clearly remember him categorizing what I listened to as 'noise,'" Jonathan recalled — there was a whimsical side to his programs. He once created an Alice in Wonderland-themed performance at Basin Harbor Club. In fact, Jonathan noted, Mel loved language and could recite from memory Lewis Carroll's famous nonsense poem "Jabberwocky" from Through the Looking-Glass.

"He loved palindromes and playing around with words," Jonathan added. "But he was very serious about the music."

Hammer agreed.

"Mel was difficult at times because he was single-minded about the music," he said. "You don't screw around with the program."

But Mel never lost his rich sense of humor, his love of storytelling or his impeccable timing. John Zion, now owner and managing director of MKI Artists, remembers first going to work for Mel as a summer intern in 2008 and meeting his gregarious boss.

- Courtesy Of The Kaplan Family

- Ynez and Mel in their garden

"I came into this incredibly quirky office," Zion said, "where I arrived every morning at eight, and he would tell me stories for about an hour, which was this incredible training in the industry." Most were about Mel's travels and the great musicians he'd known.

"He would talk with everyone," Zion added. "It didn't matter whether you were the CEO of the orchestra or the usher."

And he was generous. After Zion and his wife were married, their honeymoon consisted of a two-week musical tour of South America that Mel had arranged for them with the New York Chamber Soloists — and Zion, a violinist, sat in on performances. In every city they visited, Zion noted, Mel had previously performed in its concert hall and knew the musicians there.

In his final years, Mel was diagnosed with a seizure disorder. Karen said it pained him that he could no longer fly — though he was able to play the oboe until a year before he died.

Mel Kaplan died of old age on September 25, at 93. He is survived by his younger brother, four children, 11 grandchildren, nine great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren. Just two months later, on November 27, Ynez, also 93, joined him.

"When Dad passed away, I knew, in my heart of hearts, that Ynez would not be far behind. One couldn't live without the other," Karen said. "Now they're in heaven making music together."

— Ken Picard

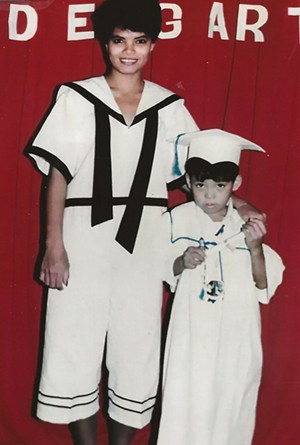

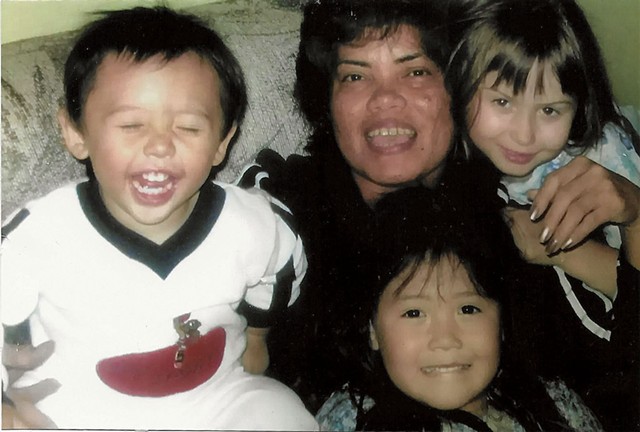

Marilou Estacio

April 9, 1960-July 18, 2022

- Courtesy

- Marilou Estacio and Jamie Bissonette

Marilou Estacio liked to smack people — all in good fun, of course. For 27 years, the spirited, petite brunette with a huge smile was the host and main server at the Dutch Mill Family Restaurant in Shelburne owned by her longtime partner, Jamie Bissonette, and his family. Marilou treated every patron at the small, diner-style eatery as if they were visiting her home, warmly welcoming older guests and kids, teasing teenagers on dates, and sassing regulars as she juggled order tickets, coffee and omelettes.

"She would always joke with customers. She'd take our menu and slap a guy's shoulder with it," Jamie said. "They just loved it. They'd say, 'Hey, how come you haven't hit me yet?'"

Jhammar Cruz, Marilou's son, recalled a conversation about the Dutch Mill among his Hinesburg coworkers. "Someone said, 'Oh, you went there? Did you get smacked by Jhammar's mom?'" he recounted with a chuckle.

Since her childhood in the Philippines, Marilou had navigated the challenges of serious kidney disease, but it was during heart surgery for a genetic condition that the 62-year-old died unexpectedly in Burlington on July 18. Hundreds of Dutch Mill patrons joined her devastated family in mourning.

Marilou's feisty, playful manner "was her way of connecting," said Dutch Mill regular Joanne Buermann of Shelburne. "Once you got to know her, you couldn't find a more empathetic person. She'd remember if you'd had a tough day and check how it was going the following week."

- Courtesy

- Marilou

Pat Long, who worked for the Colchester-based Age Well nonprofit, brought groups of seniors to the Dutch Mill for weekly lunches for more than two decades. "Marilou treated everyone like they were part of the family," Long said. "She would spend time with them, talk and joke with them. People that would never normally respond would all of a sudden come to life."

Marilou was a "spitfire" with an "infectious" personality, Long said. "It was like she flicked the light on and made everything bright."

Even though a memorial poster to Marilou graces the interior door of the restaurant, "people still ask about her 15 times a day," said Jamie's son, Michael Bissonette, who grew up in the business.

Filling the empty shoes his stepmom left at the Dutch Mill has been tough, Michael said, but it pales compared with having to tell his 5-year-old that Marilou was gone. Family photos, including several of Marilou with Michael's two young kids, plaster one wall of the Dutch Mill. "She'd play on the floor with them. She'd act like a kid," Michael said. "She was a huge family person."

Marilou spent most of her life achingly far from the Philippines and family there. The youngest of eight, she was raised by a single mom on her grandmother's pig farm just outside Manila. Marilou earned an associate's degree in nursing and, after she became a solo parent, left to work in Saudi Arabia in order to send money home. Her mother cared for Jhammar from the time he was 7.

Limited economic opportunities in the Philippines oblige many people to seek work elsewhere and leave children with family, Jhammar said. Over the years, Marilou not only financially supported her son and her mother but also helped siblings, other family members and even friends.

"She was not about taking care of herself. She would take care of you first," Jhammar said. "Sometimes she was helping someone in the Philippines and I'd say, 'Ma, stop.' But she would do it anyway."

Jhammar had a happy childhood, but it was hard growing up without his mom, he reflected. International phone calls were expensive, and they spoke infrequently, though he knew she loved him. One year, "She sent me four big birthday cakes," Jhammar recalled. "I'll never forget that."

- Courtesy

- Marilou and her son Jhammar Cruz in 1984

While in Saudi Arabia, Marilou met and married a Vermonter. By early 1988, she was living with her then-husband in the extended-stay motel on the Bissonette family's Route 7 property. At the time, Marilou was on dialysis due to kidney failure; her marriage was not healthy, either, and eventually ended.

"She was down to like 85 pounds, nothing but skin and bone," Jamie said. "I tried to help." He petitioned for a medical visa for Marilou's sister Emma to come from the Philippines to Vermont to be the donor for a successful kidney transplant.

On Labor Day 1988, Jamie and Marilou went on a first date to watch the sunset at Shelburne Beach. "We got rocks there," Jamie said. "I still have them." The following spring, she moved in.

In 1995, the Bissonettes opened the Dutch Mill Family Restaurant and Marilou took charge of the dining room. "She was a fanatic cleaner," Jamie said. "Everything had to be precise. Every day when she got done work, everything was done: the silverware rolled, every salt and pepper shaker full."

A year later, the couple completed paperwork to bring Jhammar, then 18, to Vermont. Marilou never learned to drive, but, over time, that provided mother and son a chance to connect while he ferried her to shopping, errands and church. She enjoyed buying clothes and her signature hats, tucked a rosary in every purse, and had an altar at home at which she'd pray before heading out.

Jhammar would text her when he was about 10 minutes away. Even so, he said with a smile, "sometimes I had to double-text. Sometimes I had to call again. She'd say, 'Yes, I'm coming. I'm just finishing up praying.'"

To finally have her son nearby was a gift, but, for Marilou, family went beyond blood.

Vick Miles cooked for 17 years at the Dutch Mill until he left to start his own spot nearby with Jamie and Marilou's blessing. "There was a kind of love between us you don't see so much between people working together," Miles said.

Marilou called him Big Daddy, and he called her Big Mama — ironically, since neither was large. Even when orders were flying, Marilou never lost her cool, Miles said. Sometimes, she'd say, "Big Daddy, chop, chop!" to speed him up, he said. Fifteen minutes later, she'd ask, "Big Daddy, can you slow down?"

Early on, Jamie and Marilou often headed to Burlington with Miles to shoot pool and go dancing. "She had good moves," Miles said.

As her eight grandkids joined the family — only two of whom were blood-related — Marilou also became fiercely devoted to them. They all called her Lola, Filipino for grandmother.

Three granddaughters came with Gerlie Cruz, who married Jhammar in 2016. His mother went with him to all the immigration lawyer appointments required to bring his fiancée and her girls from the Philippines to the U.S. "It was teamwork with me and Mom," Jhammar said.

- Courtesy

- Marilou and grandkids (from left) Dominique and Victoria Cruz and Emily Whitehill in the early 2000s

Gerlie's middle daughter, Raven Glaiza Antonio Cruz, was 20 when she arrived in Vermont. She and her older sister started helping out at the Dutch Mill and learning the ropes under Marilou's wing. "She was feisty, but once you got her sweet side, you're never gonna lose it," Raven said.

After work, Marilou would cook dinner and they'd watch Filipino movies or whatever was trending, Raven said. "She was fun to be with, a cool grandmother." Raven started her own food business and named it Maritela's Filipino Cuisine, partly in homage to Marilou, who became her No. 1 fan. She left little for others to buy, her granddaughter joked. "Her last text to me was, 'I'm so proud of you.'"

When it came to supporting and protecting her people, Marilou never failed. Jhammar recalled an occasion when a stranger, "a big guy," was staring at a female family member in an elevator. Marilou pulled all four feet, nine inches of herself up and demanded, "What the eff are you looking at?"

"She was a very strong woman," Michael said. About six years ago, Jamie, who has diabetes, went into a coma after a failed kidney transplant. Marilou stayed positive enough for all of them, Michael said. "She took good care of him." But, he added, if his dad gave Marilou any grief, "She'd give it right back to him."

— Melissa Pasanen

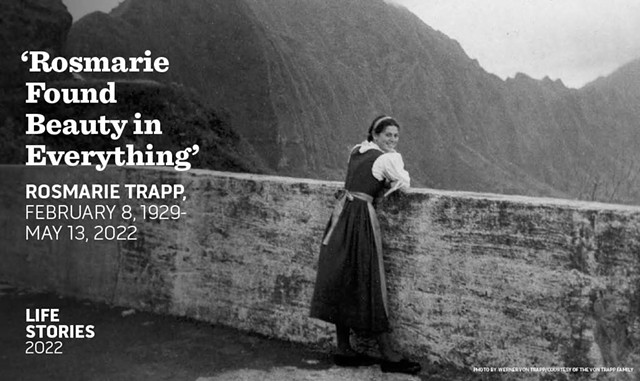

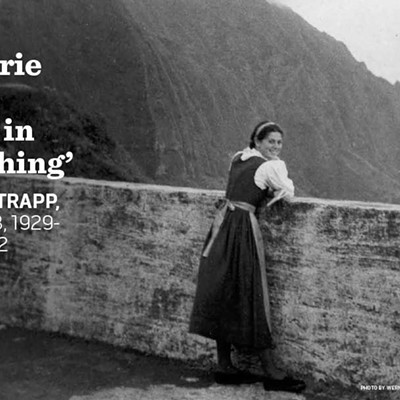

Rosmarie Trapp

February 8, 1929-May 13, 2022

- Photo By Werner Von Trapp/Courtesy Of The Von Trapp Family

- Rosmarie Trapp circa 1951 on tour in Hawaii

Growing up in a big, musical family in Waitsfield, Elisabeth von Trapp cherished her pink transistor radio. It came in a little leather case and fit in the palm of her hand. Making the radio more special, it was a gift from her aunt Rosmarie Trapp. She gave Elisabeth the radio that had been hers when she saw that her 11-year-old niece loved it.

"It was the beginning of attaching myself to the world of music. That was Rosmarie's influence," said Elisabeth, now 68 and a professional singer whose father, Werner, was Rosmarie's brother.

Rosmarie's generous and thoughtful acts and her kind consideration of others were central to her character and her way of being in the world, family and friends said. A member of the von Trapp clan, whose story inspired the partly fictionalized film The Sound of Music, Rosmarie died on May 13 in Morrisville. She was 93.

"She was probably the most gentle soul that I've ever known," said Tobias von Trapp, 67, her godson and Elisabeth's brother. "She had this childlike personality; everything got filtered with kindness." Rosmarie took to heart living the Golden Rule, he said: "Very few people wind up having that as their legacy."

Rosmarie was born on February 8, 1929, outside of Salzburg, Austria. She was the first of Georg and Maria von Trapp's three children and the eighth of his 10. Georg, an acclaimed naval commander, had seven children with his first wife. They were the original members of the Trapp Family singing group, whose repertoire included Austrian folk songs, baroque and classical music, and Mozart masses.

"They would mesmerize the audience," Elisabeth said.

Rosmarie, whose nickname was Ili, was a 9-year-old schoolgirl in 1938 when her family left Nazi-occupied Austria and traveled to the United States. (They returned to Europe in 1939 and lived in Sweden before immigrating here permanently.) Her brother Johannes, of Stowe, said his family left their homeland for three reasons.

- Courtesy Of Carol Collins

- Rosmarie Trapp

The first was that his father turned down a commission in the German Navy. "He couldn't see eye to eye with the Nazi Party," said Johannes, who will turn 84 next month.

Additionally, the oldest von Trapp sibling, Rupert, had completed medical school and, due to the "purging of Jewish doctors," professional opportunities were abundant, Johannes said. Like his father, however, Rupert would not pursue his profession under the Nazi regime.

Finally, the von Trapps were invited to perform at a birthday party for Adolf Hitler. "The family said, 'No, we can't do that,'" Johannes recounted. With a U.S. concert tour booked, they fled.

The von Trapps lived in Lower Merion, Pa., for a few years before moving to Stowe in 1942. They had visited the Lamoille County mountain town on summer trips to beat the Philadelphia-area heat, and they found their future home — high in the hills with a view of the Worcester Range — on their way to give a concert for soldiers stationed at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Stowe.

"I think the cultural landscape of Vermont, with its villages and a church and a steeple and farm fields and forested hillsides, was very evocative of Austria," Johannes said.

Young Rosmarie, who sang soprano and played the recorder, joined the family musical group at about age 12. The von Trapps would set aside their work on building and farming projects at home when it was time to pack the bus for a concert tour, Elisabeth said. For Rosmarie, this could be difficult because she had stage fright, Johannes said.

"None of us was a terribly public person except for my mother," he said. "The stage life was an effort for all of us. It was too much for Rosmarie."

But Johannes, president of Trapp Family Lodge, has fond memories of the family's early years at home in Stowe. "We were all living here at the time, and there were no guests, and life was great," he said.

In 1947, five years after the family moved to Stowe, Georg died at age 67. His death was particularly hard for 18-year-old Rosmarie, Johannes said. She mostly stopped performing, he said.

"She was a dear, sweet person," Johannes said, and "fragile emotionally."

After Georg died, the family transformed their home into a lodge, a change that occurred almost naturally, Johannes said. The size of the family made for a small crowd, and when friends visited, there were often 12 or 15 people for dinner. When family friends asked if their friends could visit, the von Trapps began to charge for the stay, he said. His mother handled lodging arrangements and other logistics. His sisters cooked meals, and Johannes washed pots and pans.

"Entertaining our guests was very simple," he said. "We would stop cooking and serving and just sing. It was great fun."

In Rosmarie's room, which had bunk beds for sleepovers, she welcomed (and entertained) her young niece and nephews. It was fun and exciting for the kids to stay with their Tante Ili, who kept a jar of pickles on her mantelpiece. Late at night, after Maria was asleep, Rosmarie led Elisabeth and her brothers downstairs to raid the kitchen. On winter visits, she skated with the kids on the pond.

"She was very playful and very outgoing," Elisabeth said.

Rosmarie, who dropped the "von" from her last name decades ago, also led sing-alongs at Trapp Family Lodge, where one of her favorite songs to sing was "You Are My Sunshine."

She also built a life outside Vermont, though the Green Mountain State was her home base and a source of pleasure. "Rosmarie found beauty in everything she looked at," her nephew Sam von Trapp said.

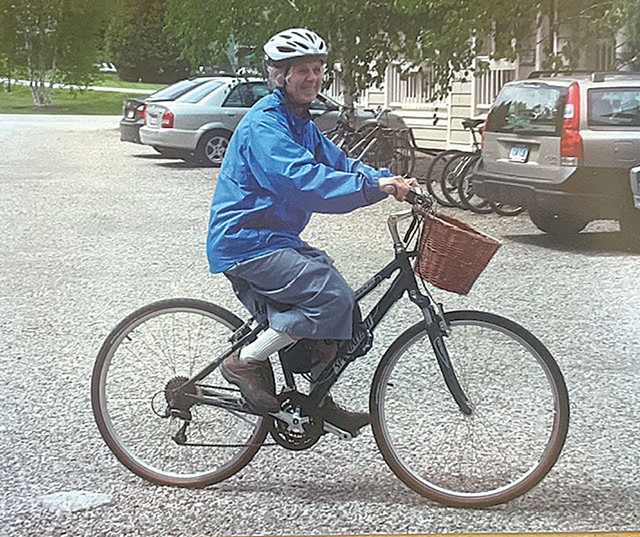

- Courtesy

- Rosmarie riding a bike

Rosmarie's trips away included living in New Guinea, where from 1956 to 1962 she worked as a lay missionary, joining her sister Maria Franziska. (Johannes was there for a portion of that time, too.) Rosmarie lived in Pittsburgh in the 1980s, her family said, where she was affiliated with a Christian community. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Rosmarie lived and worked on a kibbutz in Israel.

"She loved being there," Sam said. "God was a huge force in her life, and I think she felt very close to God in Israel."

Between excursions she maintained various Vermont projects. She ran thrift stores in Waitsfield and Stowe, where she gave away clothing to people in need, Johannes said. She was a prolific letter-writer to the Stowe Reporter, which reserved space for Rosmarie's writing under the banner "Rosmarie's Corner." She composed vignettes and slice-of-life stories and delivered them to the newsroom written in pencil on lined paper, publisher Greg Popa said.

In a June 2018 letter, Rosmarie described the "traumatic event" of her cat killing a chickadee that had come to eat at her bird feeder. She observed what occurred in the days that followed.

"When the mate kept returning for a daily search, calling his anxious 'Sol-Mi, Sol-Mi' cry, a mournful feeling came over me and my eyes started to tear up," Rosmarie wrote.

Rosmarie practiced calligraphy and was a talented spinner and crocheter. She raised sheep and carded and spun their wool. She was a longtime member of the Valley Friendly Spinners, a spinning guild she joined after meeting its organizer, Carol Collins of South Duxbury, at the Waterbury Farmers Market in 1990. Collins was demonstrating her craft when Rosmarie appeared and asked, "May I spin on your wheel?"

"Rosmarie was extremely generous and somewhat eccentric," Collins said. "And she was our most dedicated, most eager and most enthusiastic member."

For many years, Rosmarie was an active and engaged parishioner at the Stowe Community Church, the 1863 white-steepled house of worship in the village center. In the sanctuary, she read prayers she collected from the stone chapel her brother Werner built on a knoll behind the lodge. He constructed it after his return from military service in the 10th Mountain Division. Werner dedicated the chapel to Our Lady of the Peace, in gratitude for having survived the war, Tobias said.

Rosmarie described Werner's work in one of her 2018 newspaper submissions: "With a stoneboat and tractor, he hauled cement, water, sand and lots of rocks, hand-picked from stone walls up the hill. Now it is a goal for many hikers."

Decades after her brother built the chapel, Rosmarie would hike half a mile to collect prayers that visitors wrote and left there.

"We read them aloud to each other," Marylou Durett, the church's administrative assistant, said. "And, of course, to God."

In 2017, Rosmarie moved into an apartment on the Mountain Road, where she lived with her cat, Trinity. Johannes smiled when he recalled visiting his sister there. He noted that she always had grapes and dates for his young grandsons, her grand-nephews, who are among the youngest of the scores of von Trapp descendants who survive Rosmarie.

"The last five years of her life were the most peaceful," Johannes said.

— Sally Pollak

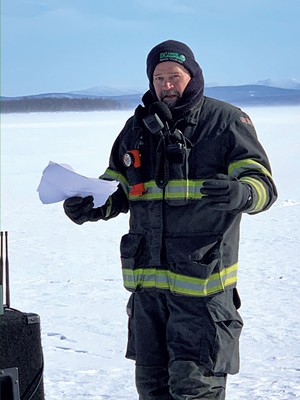

Dwayne James Cormier

August 28, 1966-October 16, 2022

- Courtesy

- Top row: Dwayne Cormier, Jonathan Cormier, Ryan Cormier; bottom row: Pam Cuneo, Shachi Desai and Sarah Cormier on Thanksgiving in 2021 in Louisiana

When brothers Dwayne and George Cormier were kids in the 1970s, one of their favorite pastimes was fixing broken machinery they had retrieved from the dump. They resurrected a riding lawn mower to cut neighbors' lawns in their hometown of Breaux Bridge, La. They revived toaster ovens, fixed vacuum cleaners and found a particularly ingenious way to use a certain toy.

"We made an alarm system with an old toy sewing machine, trying to keep our sisters out of our room," George said with a chuckle by phone from his offshore jobsite. The boys had five sisters. "We attached a piece of wire and some tinfoil so a little vibration would make it go off."

Such smarts and resourcefulness would carry into the brothers' adulthood, as would generosity, kindness and a work ethic that ensured success. But one brother's life was cut short unexpectedly this year.

Dwayne died of sudden cardiac arrest in his North Hero home on Sunday, October 16, at age 56. He left behind his beloved wife, Pam Cuneo; his three adult children; numerous siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles; countless friends; and a community that wonders how it will function without him.

Not only did Dwayne employ as many as 18 people at a time at his company, DC Energy Innovations, but he was a member of the North Hero Volunteer Fire Department for more than 20 years, and he volunteered for the North Hero Historical Society, the North Hero School and the annual Great Ice! celebration.

A certified master electrician, he knew what all the buttons at the Ed Weed Fish Culture Station in Grand Isle did, how to raise the old drawbridge on Route 2, how everything ran at the North Hero Town Hall and at neighboring store Hero's Welcome, and how to work the elementary school alarm, said fellow North Hero firefighter and longtime friend Jim Benson.

"He had the keys and the codes for every place. Dwayne could go anywhere," Benson said. "He could fix anything and everything. Nothing's gonna run the same anymore, ever."

- Courtesy Of Jim Benson

- Dwayne volunteering at North Hero's Great Ice! in February 2020

To the very last minute of his life, Dwayne "loved his work," Pam said. "He loved fixing things. He loved helping people."

He was a consummate learner and patient teacher who never took shortcuts. "If he couldn't do it safely, the right way, he wouldn't do it," George remarked.

And Dwayne's generosity was boundless. "Dwayne was a giver," said North Hero fire chief Mike Murdock in his eulogy at the October 23 memorial service at the town hall. "He was always willing to help in just about any situation ... And Dwayne had one tool that just put people at ease: It was his smile." Dwayne's slight Louisiana accent, coupled with that big smile and kind eyes, epitomized southern hospitality.

Despite his skills and abilities, Dwayne was humble and could be soft-spoken. "He never bragged about anything he did," his aunt Hazel Theriot said by phone from Louisiana. "On the contrary, he would play down his accomplishments."

In their younger years, Dwayne and George were "very industrious, innovative and curious children," Hazel recalled. But their lives weren't easy. Their father, Earl Cormier, who was Hazel's brother, was in high demand as a ranch hand on Louisiana cattle farms. He was an alcoholic, Hazel said, and their mother, Yvonne, wasn't very nurturing.

"As soon as we could ride horses, we were out there helping my dad with cattle," George recalled.

Earl and Yvonne divorced when the boys were in their early teens, and the family split: The boys and their sister Laura went with Earl, and three girls stayed with Yvonne. The oldest girl had already married, Hazel said.

Earl stopped working as a ranch hand and began traveling a lot. "My dad was hardly ever around," George recalled. He and Dwayne relied on each other and various family members, including Hazel, her husband and the children's grandparents. "They would invite us to come eat good home-cooked meals," George said.

In high school, Dwayne continued to work with horses. According to old papers Pam found in their home, he studied in Oklahoma City to become a farrier in 1984, at age 18. Before he graduated from high school (a few years later than his peers), the young man had started his own farrier business. He also took college courses in electrical systems and electronics. By 1987, he had a job caring for Arabian horses at a prestigious farm in Florida.

- Courtesy Of Pam Cuneo

- Dwayne, Pam and Trooper in 2022

That's where he met his first wife, Sandy, who also worked at the farm. They had three children, Jonathan, Sarah and Ryan, between 1988 and 1994, but they divorced when the kids were quite young. Sandy moved to North Hero, in her home state of Vermont, and Dwayne followed her there. "I'm pretty certain that Dwayne moved to Vermont because he didn't want his kids growing up without a dad," Hazel surmised. "He grew up without much of a dad or a mom. He wanted to be more to his kids ... I was so proud of him for that."

In a recent interview, Dwayne's daughter, Sarah, now 32, said he always lived a short distance from their mother's house. "He was very present to make sure that we were successful," she said. He was the stricter parent and grounded her when her grades dropped. But he also was very loving, taught her how to square dance and shared his inventions with her.

"He was very creative and had an amazing brain," Sarah recalled as she described one of Dwayne's sketches of balls circulating in water. "He was always trying to invent solutions for making energy."

On Sarah's 16th birthday, Dwayne brought her to the North Hero House to get her first job. Antisocial and shy at the time, she said, she was initially terrified of the restaurant work. But she stuck it out, and the job changed her life.

"It absolutely, 100 percent helped me, in my life, blossom as a young teenager, a young adult," said Sarah, now the general manager of Deep City restaurant and bar in Burlington.

Around the time of his divorce, Dwayne began apprenticing as an electrician at Hammond Electric in Colchester. Upon completing the four-year program in 1996, he tested well enough to become a master electrician and soon after began working for Hallam-ICS, a South Burlington engineering company.

At a local line dancing event in 1997, he met Pam, his second wife and the love of his life. For their first date, he invited her to a Saint Patrick's Day dance and brought her a corsage.

"No one had ever given me a corsage before," Pam recalled. "I was like, Wow, this is a really sweet guy."

For the second date, Dwayne drove nearly an hour to pick up Pam and take her out to dinner. On the third date, he cooked dinner for her and his three young kids.

The couple was engaged in 2000 and married in 2008, an event postponed numerous times by their hectic lives, Pam said. Family members felt they were a great match. "Pam was so good for Dwayne," Hazel opined. "She was just wonderful. I think he flourished with her."

Pam's brother, David, appreciated Dwayne just as much. "It put me at ease, knowing that my sister was in the hands of somebody as capable and loving as he was," he said. As for Dwayne's children, they "were always super sweet to me and never made me feel like I didn't belong," Pam said.

In 2002, Dwayne launched DC Energy Innovations, which installs and maintains commercial and residential electrical, solar, and security systems and repairs wind turbine inverters and other electronics. Over the years, he trained 25 apprentices through a Vermont Department of Labor program. His employees now run the business.

But other projects of Dwayne's are headed for detours. His joy in fixing broken things led him to fill his yard with machines and parts. Among them was a 1968 32-foot Chris Craft Sea Skiff double-engine touring boat designed to sleep four, friend Ev Kettler said. A boat and mandolin builder himself, Kettler has been tasked with finding someone to take the boat, named The Naughty Gal, for free — and isn't having much luck.

"He has been tinkering with it for 22 years," Pam said of Dwayne and his boat, "and it has never been in the water in all that time." He was eternally optimistic about his capacity to fix things, she said, but "He wasn't great with time management."

So how did he run a thriving business, volunteer for numerous local organizations and raise a family? "He would just get up really early in the morning and go to work," said Benson, his friend and fellow firefighter. "He had no time extra to give to anybody, but he did it anyway."

The North Hero Volunteer Fire Department responds to about 70 calls per year, Benson said, and Dwayne would come to about 60 of them. A few years ago, Dwayne decided the department needed a better way to rescue people and animals from unstable lake ice, so he researched solutions and helped the department procure an air boat, a flat-bottomed craft propelled by a large fan.

- Courtesy Of Pam Cuneo

- Dwayne as a teen

Not long after the firefighters were trained to use the boat, a call came in from the Clarenceville Firemen's Association in Québec. Dwayne and his air boat saved three men from icy deaths. Afterward, "Dwayne was glowing," fire chief Murdock recalled. "He was so happy. I think he smiled nonstop for a week."

Dwayne's inventiveness also shone in the used Zamboni he purchased and fixed up to condition a skating area on the lake. He built various attractions with family and friends for North Hero's annual Great Ice! festival: notably, the dunk-the-fireman game and colored-light ice labyrinths. Dwayne posted videos about some of his projects on his YouTube channel, including one with more than 29,000 views on how to fix a vent blower in a 2014 Dodge Ram.

On Sundays, Dwayne and Pam, a full-time endodontic assistant, took time to sleep in, take walks with their dog, Trooper, and practice Argentine tango. They'd begun learning the dance roughly 10 years ago and devoted many hours to drills and social time with tango friends.

Dwayne had a heart condition called ventricular tachycardia and got a pacemaker in his early thirties. It was on one of those Sundays that his heart went into ventricular fibrillation and the pacemaker couldn't correct it. He had a heart attack and died quickly, unresponsive to Pam's expertly administered CPR.

At Dwayne's memorial service, there were 60 firefighters from local departments in full uniform, 18 fire trucks, two ambulances, one police car and the air boat. The hall was packed with people. "I've never been to a firefighter funeral so big," Benson said.

Over the years, many people looked up to Dwayne: George, Benson, David and Sarah among them. "I'm always trying to be like him," Sarah said.

As fire chief Murdock came to the end of his eulogy and people were wiping away tears, he remarked, "Just imagine how beautiful the world would be if we all were a little more like Dwayne."

— Elizabeth M. Seyler

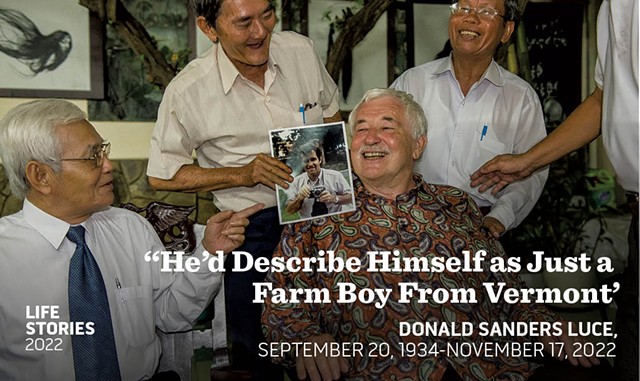

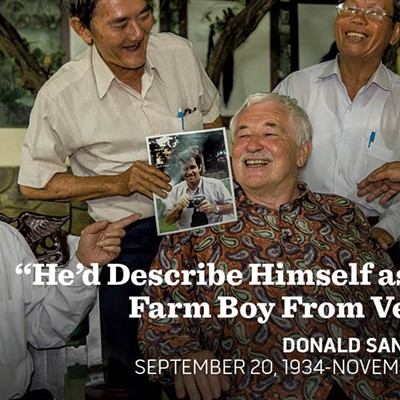

Donald Sanders Luce

September 20, 1934-November 17, 2022

- Photos Courtesy Of Ted Lieverman

- Don Luce (center) with former prisoners of the South Vietnamese government

Growing up on a dairy farm in East Calais, Tim Luce said last week, he was schooled in "traditional values" and was taught "the difference between right and wrong."

His uncle Don Luce would have been brought up the same way on that same hardscrabble farm, Tim, 68, added. But Don, who died of a heart attack last month at age 88, underwent sharp shifts in his understanding of what constituted right and wrong.

Initially an admirer of ultraright senator Joseph McCarthy and a believer that "America was doing good in the world," Don became an outspoken and influential opponent of the U.S. war in Vietnam. His impact was such that Graham Martin, the last U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, said at a Senate hearing in 1976 that an antiwar group led by Don had proved to be "one of the best propaganda and pressure campaigns the world has ever seen." In fact, Martin added, a "principal element" in the U.S. defeat in Vietnam was "the multifaceted activities of Mr. Don Luce."

As further — and final — testaments to his place in American history, Luce's life was extensively chronicled in obituaries in both the New York Times and the Washington Post. The Times' headline described Luce as an "activist who helped end the Vietnam war."

- Photos Courtesy Of Ted Lieverman

- Don Luce

His opposition to the conflict in Indochina resonated so powerfully because Don was seen as an idealistic young American with personally acquired knowledge of Vietnamese culture and society. He lived in Vietnam from 1958 until his expulsion in 1971, working most of that time as an agriculture specialist with Washington, D.C.-based International Voluntary Services. Fluent in Vietnamese, Don was able to see the war through the eyes of peasants and displaced rural families. In a widely circulated open letter to president Lyndon Johnson in 1967, he and 48 other disillusioned IVS staffers warned that "the war as it is presently being waged is self-defeating in approach."

He expanded that critique in a 1969 book, Vietnam: The Unheard Voices, that he coauthored with former IVS team leader John Sommer. "Because American understanding of the people has been so limited," they wrote, "the tactics devised to assist them have been either ineffective or counterproductive. They have served to create more Viet Cong than they have destroyed."

Don succeeded most dramatically in stoking revulsion against the war through his 1970 exposé of a clandestine torture center run by the U.S.-allied South Vietnam government on an island 60 miles off the country's coast. He had accompanied a U.S. congressional delegation to the Central Intelligence Agency-funded installation, which South Vietnam officials insisted was an ordinary prison. But an ex-prisoner had given Don a hand-drawn map that showed the location of a secret door in the prison leading to a warren of tiny cells known as tiger cages.

Two members of Congress were with Don as one of their aides took photos of some of the 500 political opponents of the South Vietnam government who were caged in horrific conditions. Don later wrote: "I remember clearly the terrible stench of diarrhea and the open sores where shackles cut into prisoners' ankles."

The pictures ran in a July 1970 edition of mass-market Life magazine. They triggered widespread protests in the U.S. and international condemnations, which forced the South Vietnamese authorities to stop putting people in cages too cramped for standing upright.

- Photos Courtesy Of Ted Lieverman

- Don (left) and Mark Bonacci

Don's role in uncovering the atrocities resulted in his expulsion from Vietnam. It also nearly cost him his life. Don's husband, Mark Bonacci, recalled in an interview that "several attempts were made to kill him." One involved putting a poisonous snake in Don's bed while he was away from his Saigon apartment.

"Don wasn't the neatest person," Mark said, "so when he saw that his bed had been made, he was immediately suspicious." The snake — known in Vietnam as a "two-step" because that's how far someone would get after being bitten — wriggled under the bedcovers. "Don's big regret afterwards was that he had had to kill the snake," Mark recounted.

Don was gentle and soft-spoken with an understated style of leadership, said his widower, a professor of human services at Niagara County Community College in New York. He was also "very naïve," believing that people are basically good and deserved to be taken on their own terms. That attitude extended even to Pol Pot, the Cambodian communist leader held responsible for the deaths of nearly 2 million civilians. Don shared a chicken dinner with Pol Pot at his jungle hideaway in 1979 while accompanying a television crew on an interview assignment.

"I would say Pol Pot is an evil madman," Mark said. "But Don would say, 'If we don't try to understand his kind of twisted logic, it could happen again.'"

Don and Mark became partners after meeting in a Greenwich Village bar in 1979; they married in 2008. During the 1990s, while Don worked at IVS' office in Washington, Mark lived in Niagara Falls, N.Y., and they commuted to be together on weekends.

Don moved to Niagara Falls in 1997 and went to work for Community Missions of Niagara Frontier, a nonprofit that provides mental health services and operates a shelter and soup kitchen. Don did publicity for the organization and also worked directly with clients. Mark recently received a condolence note from a woman whom Don had assisted in finding and moving into an affordable apartment.

- Photos Courtesy Of Ted Lieverman

- Don outside his old apartment in Saigon

It was life on that East Calais dairy farm that set Don on the course that took him to Vietnam, several other countries and to a Niagara Falls agency caring for indigent people. When giving speeches around the country, Don would explain that his actions were based on values, not ideology, Mark said: "He'd describe himself as just a farm boy from Vermont."

The 220-acre dairy farm owned by his parents, Collins Luce and Margaret (Sanders) Luce, relied on horses for hauling and on wood for heating, Don recalled in a 2015 YouTube interview. His father, "a strong Republican," had wanted him to become a mechanic or something similarly "manly," while his mother, an elementary school teacher and "a strong Democrat," wanted him to attend college.

A voracious reader and a diligent student, Don gained admission to the University of Vermont on a scholarship. He graduated in 1956 with a degree in farm management and earned a master's in agricultural development from Cornell University in 1958.

While at UVM, Don worked in the cafeteria and as a resident assistant in a dorm. "The first kind of radical thing I did," he said on YouTube, was to defend a group of Korean War veterans whom the dean of students had wanted to expel from UVM because they had been caught with a single can of beer. Don argued that expulsion would wreck the lives of these young men. "And we won" that case, he recalled with a smile.

Don's three siblings — now all deceased — had remained in Vermont all their lives, nephew Tim said. "Uncle Don was different," he added. "He wanted to get out and see the world. Which he sure did do."

— Kevin J. Kelley

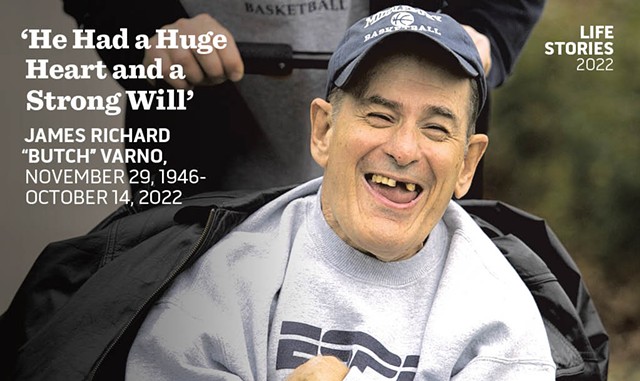

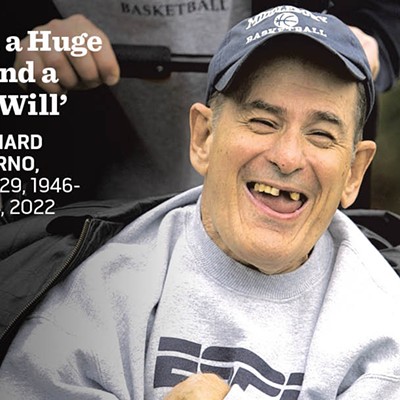

James Richard "Butch" Varno

November 29, 1946-October 14, 2022

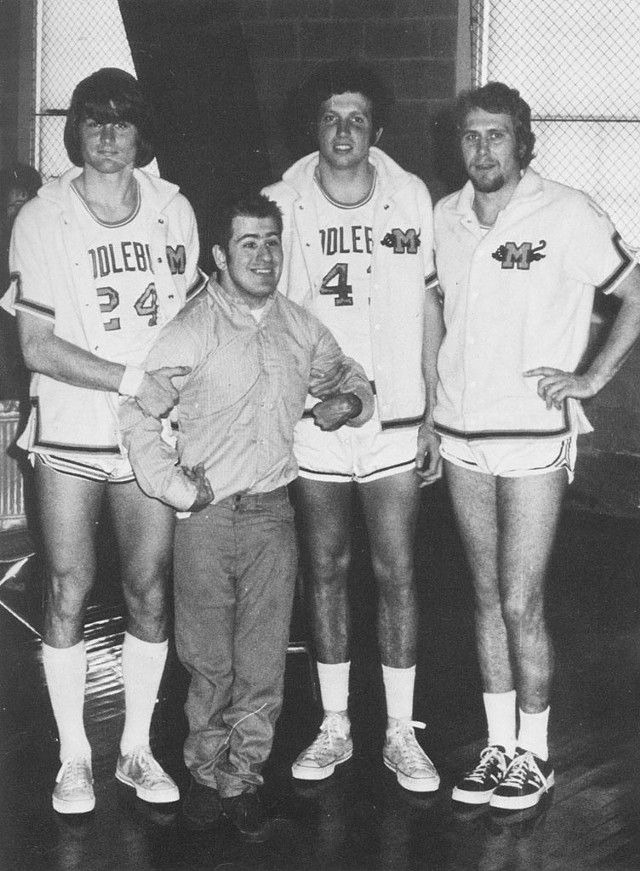

- Courtesy Of The Middlebury College Center For Community Engagement

- Butch Varno with former Middlebury College basketball player Kevin Kelleher Jr.

His full name was James Richard Varno, but everyone knew him as Butch. He loved chocolate cake, Old Spice aftershave and watching James Bond movies, particularly Goldfinger, according to his cousin, Rita Brown. And in the words of the late Russ Reilly, Middlebury College's former athletic director and men's basketball coach, Butch possessed an "unsinkable spirit."

Butch was born in Middlebury, lived his whole life there and died of pneumonia at Helen Porter Rehabilitation & Nursing on October 14. He was six weeks shy of his 76th birthday.

Butch was a small-town person with a big story that reached sports fans around the world — not because he was an athlete, though he wanted to be one, but because he was a superfan of Middlebury College's football and men's basketball teams for more than 60 years. He liked watching different sports, both in person and on TV, but those two teams and the generations of athletes who played on them were what he loved most.

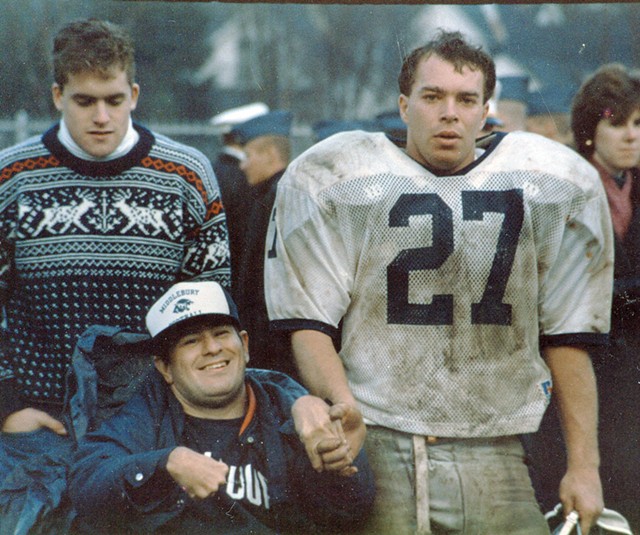

The story that made Butch a little bit famous goes like this: When he was 13, his grandmother, Mabel Varno, took him to a Middlebury College football game, and it started to snow partway through. Butch was born with cerebral palsy and needed a wheelchair to get around. As his grandmother wheeled him home, the chair got stuck in the snow. A college student named Roger Ralph happened to be driving by and stopped to help.

After Ralph gave Butch and Mabel a ride home that evening, Ralph got some of his friends together to give Butch rides to subsequent games. Football players brought Butch to basketball games; basketball players brought him to football games. The students would go to his home in town, where he lived with his mother, Helen Varno, and load him and his wheelchair into their car. At the games, they'd help him stand for the national anthem. Together, they'd cheer the good plays, commiserate over the lousy ones, eat snacks, talk sports. This went on for decades.

"It just became ingrained in our athletic program that this is what we do," said Jeff Brown (no relation to Rita), head coach of the Middlebury men's basketball team since 1997 and Butch's legal guardian for the last three years of his life.

In 2007, "CBS Evening News" ran a feature story on the tradition that had become known as "Picking Up Butch." Reilly told the interviewer, "I'm sure every student going into this is wondering, What does this really mean? Who is this guy? Why is he so special?"

- Courtesy Of The Middlebury College Center For Community Engagement

- Butch with members of the Middlebury College football team

It was his smile, said Tiffany Nourse Sargent, the former director of Middlebury College's Center for Community Engagement. "Butch would just light up when he saw somebody he knew or made a new friend," she said. "He had a huge heart and a strong will. He was aware of his vulnerability, but he never let it hold him back. Whatever was going on, he wanted to be a part of it."

Before the CBS feature, Sports Illustrated published a story about Butch; features by ESPN and the Boston Globe followed. Butch relished the spotlight.

"He loved to have his picture taken, no doubt about that," Rita recalled.

When Middlebury College president Laurie Patton was inaugurated in 2015, Butch was the first person she welcomed by name in her remarks.

More recently, Butch was invited to attend a Boston Red Sox game.

"We were sitting right at field level, and around the sixth inning, they announced that Butch Varno was at the game," recalled Brown, who accompanied Butch to Fenway Park. "The cameras zeroed in on him and put him on the jumbotron. He was over the moon!"

While Butch appreciated the attention from sports journalists, college presidents and stadium cameras, he valued the attention he got from college students far more.

"He loved the interactions, and he loved being on campus," Sargent said. "There was nothing he liked better than being surrounded by friends at a football game or basketball game."

In the 1990s, after Butch had been going to Middlebury games for 30 years, staff at the Center for Community Engagement built a formal volunteer program around him and dubbed it Butch's Team. The goal was to create a "fuller connection," according to Sargent.

"Athletics always played a huge role, and we collaborated with them to fill in gaps," she said. "There were days and weeks when the teams weren't in season, and that could get lonely for Butch."

Student volunteers visited Butch at his house and later at Helen Porter, where they played Monopoly and read the college newspaper together. They went for walks because he loved being outside. Students were trained to use a college van that had a wheelchair lift so they could transport him around town even more safely.

"He was such a loving and enthusiastic person," said Margaux Eller, a Middlebury junior who was part of Butch's Team. "He really cared about all of our lives. He knew who my family members were, and he'd always ask how they were doing. He'd ask how I was doing in school. If I told him I was struggling in one of my classes, he'd be so encouraging. He'd say, 'You're smart; you got this.' I really appreciated that."

Butch was smart, too, Rita said. With help from college-student tutors, he earned his GED in 2003. He maintained a painstaking and extensive collection of news clippings about his favorite sports teams, which he stored in an old-fashioned briefcase. While being at home most of the time meant he watched a lot of TV, it was C-SPAN as much as it was ESPN. Presidential politics fascinated him.

"He always wanted to talk about what was going on nationally or internationally," Sargent said.

He liked President Joe Biden, according to Rita. Didn't care much for Donald Trump. Loved the Los Angeles Dodgers. You couldn't even mention the New York Yankees to him.

Rita knew Butch better than anyone, after growing up with him and helping to take care of him throughout his life. She knew that he preferred orange Crush over orange Fanta, that his nickname came from the short buzzed haircuts he got as a kid and that, before he moved to Helen Porter in 2006, he sometimes drank a gallon of milk a day.

He loved listening to classic rock on an old-school boom box — the heavier the bass, the better. At Helen Porter, he liked to hang out near the front entrance and watch the cars drive in and out, even when he wasn't waiting for friends from the college to come for a visit.

"To anybody who walked by, Butch would say, 'Hello, how are you today?'" Rita said. "It didn't matter whether he knew the person or not. He always had a greeting for them."

That goodwill extended, of course, to the student athletes whom he adored so much. During halftime huddles at basketball games, Butch would often join in and offer words of encouragement to the players.

- Courtesy Of The Middlebury College Center For Community Engagement

- Butch with members of the 1972-73 Middlebury College men's basketball team

"His message frequently centered around how fortunate the athletes were," Brown said. "He would say, 'I wish I could play, but I'm in this chair, so I can't.' It was a great lesson to learn as a college student — to really appreciate what you have."

Butch was open about his disability and how it affected him. In his interview for the ESPN feature, he said, "That's what cerebral palsy does — it takes away what you want to do with your life." He didn't specify what that might have been, besides being able to play sports. But Rita knows.

"Butch always said that he wished he could have been a coach," she said.

In a way, he was.

"He reminded us of why being together was important at all moments of life," Patton and director of athletics Erin Quinn wrote in a message to the campus community after Butch died.

"His impact was just amazing," Brown added. "At football games, I'd spend part of the game sitting with him, and there was always a constant flow of people coming over to say hello."

Butch's legacy will extend beyond those friendly moments, thanks to a group of alumni who, years ago, contributed money to help the college help Butch. The Center for Community Engagement established a small endowment and named it the Community Response Fund. One of the conditions stated that upon Butch's death, the endowment would be renamed the Butch Varno Community Response Fund and would be used to support other local needs.

In 2008, when Helen Varno died, Reilly became Butch's legal guardian. When Reilly died in 2019, Brown took on that role.

"When I think of all the things I've been able to do at Middlebury College, that's probably my No. 1 favorite thing," he said. "To be there for Butch really deepened our relationship as friends."

Butch would have loved to hear that. And he would have loved the fact that three basketball players and three football players served as pallbearers at his funeral.

"He was quite proud of the depth of loyalty that people felt to and for him," Sargent said.

— Jennifer Sutton

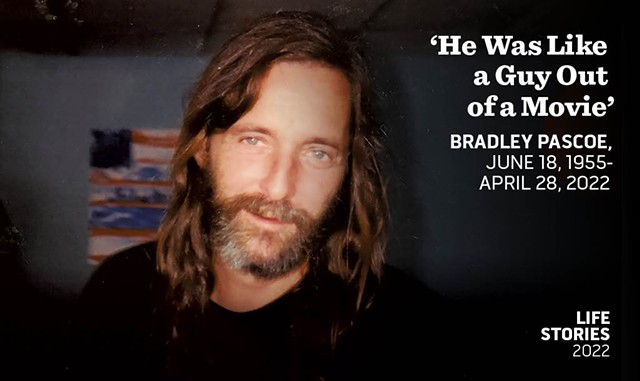

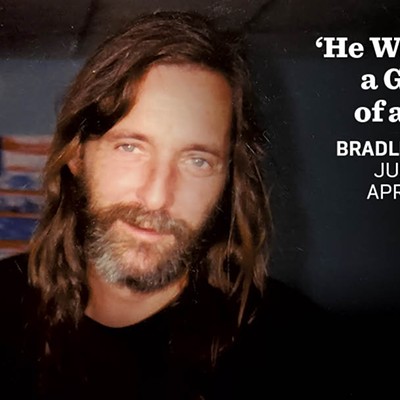

Bradley Pascoe

June 18, 1955-April 28, 2022

- Courtesy Of Cassandra Edson

- Bradley Pascoe

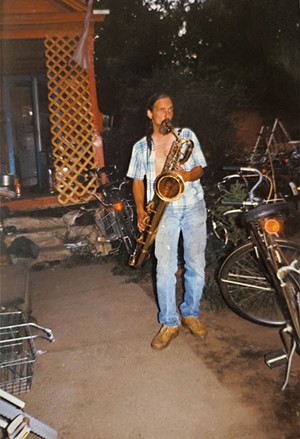

If you spent some quality time in the downtown Burlington bar and music scene over the past two decades, you probably caught a glimpse of Bradley Pascoe, one of the Queen City's great nightlife flâneurs and unofficial after-hours ambassadors. In his debonair suit and top hat, Brad would roam the streets, selling roses to late-night revelers or simply giving them away in exchange for a smile.

Nothing brought Brad more joy than finding beauty in the world and sharing it with others. This quest occasionally led him to some weird places — such as the dumpster of a wholesale florist on Shelburne Road, from which he rescued his roses. "He was like a guy out of a movie," said his longtime friend, Gayle Callahan. "Half the time, if he was drinking, he wouldn't make it home, and he'd sleep right where he was on the street. But he still dressed the part of a gentleman, and he would give you the shirt off his back, even though he had nothing."

Brad was a master of improvisation. A virtuosic guitar player, he could transform a social gathering into an intimate communal experience, and he was renowned for his ability to whip up a delicious meal from a bare cupboard. His passion for music might have been rivaled only by his love of working on motorcycles and bikes. For years, he ran his own shop, Pascoe Cycles, which he began in his front yard in the Old North End and later moved to Pearl Street. But just as he did with his roses, he would sooner give a bike away for free than turn down a customer who couldn't afford one. He had a troubadour's soul and a mischievous charm, said Callahan: "He was one of the few people I knew who could be working on his bike in one breath and reciting Yeats in another."

Until the end of his life, Brad struggled with alcoholism, which likely contributed to his death. He died in April in Tucson, Ariz., at the age of 66, following complications caused by a gastric ulcer.

Brad grew up in Lexington, Mass., the younger of two sons. His mother, Corinne McIntyre, now in her nineties, was an artist; his father, Kenneth, who died in 2014, was an engineer and a brigadier general in the National Guard. Brad's older brother, Jeff, remembers him as a kid with a big imagination and a soft heart. He rarely went anywhere without his blue corduroy elephant, Raisin, whose birthday the family celebrated.

When he was 4 years old, his parents gave him his first guitar for Christmas, and from that day on, he never stopped playing music. In first or second grade, Brad took to wearing cowboy boots, which became his signature footwear as an adult. For a time, he kept a chicken as a pet and walked it around the neighborhood on a leash.

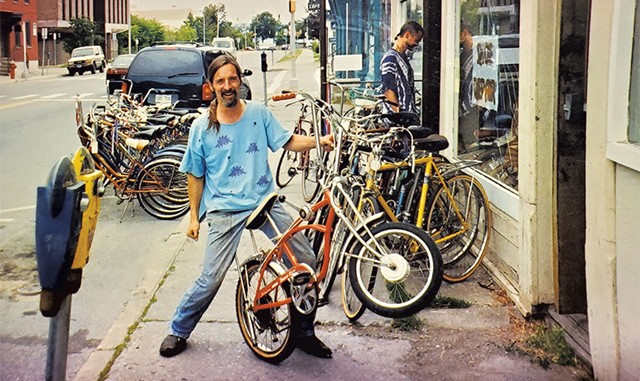

- Courtesy Of Cassandra Edson

- Bradley Pascoe outside his bike shop in Burlington in the late '90s/early 2000s

When the boys were 10 and 12 years old, their parents divorced. From that point on, Jeff said, "we weren't subject to a whole lot of discipline or supervision." Left mostly to their own devices, they followed starkly different paths: While Jeff did his homework and went to sleep at a reasonable hour, Brad snuck out his bedroom window and caroused. (Precisely what he got up to is still a mystery to Jeff, though he suspects it involved music and, quite possibly, weed.) For years, Jeff said, he was clueless about Brad's nocturnal life, not that he thinks his intervention would have made a lick of difference. "Brad was going to be Brad, no matter what," he said.

After graduating from high school in 1973, Brad enlisted in the U.S. Navy, without telling his parents, and spent his duty assignment in Italy. He opposed the Vietnam War, according to his former partner, Cassandra Edson, but he "was not the kind of hippie who was going to avoid the war," as she put it. He never saw combat, but he knew people who fought and died. "I think that absolutely haunted him his whole life," Callahan said.

In 1980, not long after he got out of the Navy, Brad came to Burlington, where he found his spiritual home in the city's music and biker scenes. The first time Edson met him, on New Year's Eve 1990, he was rebuilding his motorcycle from the sea of parts he'd scattered across every available inch of surface area in his room.

The two started dating shortly afterward, and in 1992 they had a daughter, Ariel. After Ariel was born, the couple moved into a red Victorian with sagging floors on North Winooski Avenue, which their friends came to know as "the Red House." The couple split up when Ariel was a year old, but Brad remained a devoted and whimsical co-parent, Edson said: "I earned the money and made sure the housing was paid for, but he made sure that Ariel had a magical childhood."

When Ariel spent weekends with Brad, she got to know the neighborhood characters who would drop by the Red House to hear him play guitar on the porch. "He showed Ariel how to hang out with people in an unscripted way," Edson said. The two wrote music together, and they shared a fondness for cats, two of which Brad adopted for her.

When Brad's landlord got fed up with the bicycle menagerie in the front yard, in the early '90s, Brad moved his shop to Pearl Street, near Bove's restaurant, where he fixed and sold bikes until 2003. He never made much money, according to Callahan, but for Brad, money was never the point. "He just wanted to put people on two wheels," she said.

Brad had studied music at Burlington College for a few semesters in the mid-'80s, but he preferred to hone his craft by playing his 12-string Martin guitar for other people. He performed his repertoire of original compositions and folk and Americana songs — John Prine, Willie Nelson and Bob Seger were some of his mainstays — at open mics around town. Sometimes, Brad would stand outside the Flynn and serenade theatergoers as they came and went, which is how Callahan and her husband, Joe, first met him. "He had this amazing soul, like no one else I'd ever met," Callahan said. "He would look you in the eye and know just what song to play for you, and you could feel the decent human and free spirit he was."

After racking up too many DUIs, Brad lost his driver's license, along with his ability to legally cruise around on his '65 Harley Davidson Pan-Shovel named Gandalf. (According to Callahan, Brad, ever the improviser, would occasionally change the paint job on Gandalf to keep the cops off his trail.) But Brad wasn't the sort to let logistics cramp his style. Just before the Callahans got married, in 1996, he had surgery at the Veterans Administration hospital in White River Junction to remove a cancerous skin tumor. After his procedure, against medical advice, he signed himself out and hitchhiked the 45 or so miles to West Topsham Church. He arrived just in time to play guitar at the Callahans' wedding ceremony.

- Courtesy Of Cassandra Edson

- Bradley outside his home on North Winooski Avenue in Burlington

By all accounts, Brad had perfect pitch and a finely calibrated ear. "He could play any song I asked him to play," said Courtney Burns, whom Brad married in 2009. "Even those Joni Mitchell chords that are, like, impossible." (Courtney, who frequented the bars of Burlington, had received several roses from Brad over the years before they officially got together.)

After he and Burns got married, they moved to her parents' house in Georgia, Vt., where Brad started refurbishing antique bikes and selling them on Craigslist. In the summer, he and Courtney would crisscross the state in search of rare and unusual specimens. Once, at a yard sale in Fletcher, Courtney remembers, Brad spotted an antique postal carrier bike, for which he paid $15. He later sold it for more than $1,000.

Courtney and Brad split up in 2017, though they were still legally married when Brad died. Until the end of his life, she said, they cared deeply for each other. "You couldn't not fall in love with Brad," Courtney said. "He had this presence that was almost magical."

After he and Courtney broke up, Brad moved to Tucson, where the Callahans had a condo. The end of his relationship with Courtney had been painful, Gayle Callahan said, and he hoped a change of scenery would do him good.

His health was beginning to deteriorate, but in Tucson, Brad seemed to turn a kind of spiritual corner. Following a death in his family, Brad had come into some money, and he used it to take over the lease of the Callahans' condo and buy himself a 2004 Porsche Boxster convertible, which he drove with the top down, wearing a dapper white button-down and a leather vest. He played guitar by the pool under the stars each night; at the local watering hole, people would ask him questions about their motorcycles, and Brad would offer his expertise.

"I feel like, for a long time in his life, he was trying to get to a place he couldn't get to — not just a physical place but an emotional place," Callahan said. "And I think he finally got there."

— Chelsea Edgar

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.