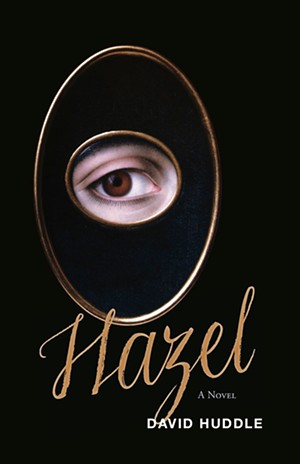

- Hazel by David Huddle, Tupelo Press, 199 pages. $17.95.

Sad. Lonely. Odd. That's how the denizens of late 20th-century Burlington might describe Hazel Hicks, the heroine of David Huddle's new novel Hazel. A lifelong spinster and diligent state employee, Hazel has "felt the need to get away from people" since adolescence. After moving in with her first and last boyfriend, she diagnosed herself as having "a kind of emotional allergy to love."

Hazel doesn't have friends — unless you count her beloved nephew, who narrates sections of the book; or the silent homeless guy who briefly visits her backyard; or the VPIRG canvasser she nearly murders with the shotgun she never wanted in the first place (it's a long story).

"Only a dozen or so people in my lifetime have found my conversation desirable," Hazel muses at one point. "Of those I've been able to tolerate maybe five or six — and one of those was a dead man I chose to continue talking to for nearly a year after I read his obituary."

It should be clear by this point that Hazel may indeed be sad, lonely and odd, but she's not boring. Indeed, her nephew, John Robert, contends "that somehow [her] life has been exceptional," to which she ripostes, "About as exceptional as the house salad with ranch dressing."

Hazel is one of two works by longtime Burlington author Huddle that were released this year; the other is a poetry collection called My Surly Heart from Southern Messenger Poets. This highly engaging novel takes the form of a collection of linked vignettes examining Hazel — or "Ms. Hicks," as she's sometimes called — from various perspectives. Many of its chapters were previously published as stories in literary journals, and they exhibit considerable stylistic variety — third and first person, past and present tense.

Generally, Hazel's point of view alternates with John Robert's short descriptions of photos he found in his aunt's collection. But two chapters give voice to people who encountered Hazel at some point in their lives and were changed by her.

These last perspectives hint at a sly undercurrent in the novel's anecdotes. Despite her antisocial nature, Hazel relates to the people around her, "witnesses" them (as Huddle puts it) and even transforms them.

How? Well, Hazel sees people, a skill that Huddle suggests is rarer than we might think. In the novel's opening chapter, teenage Hazel attends a Golden Gloves boxing match at Memorial Auditorium with an inarticulate classmate. Through her eyes, we watch this boy enter a "trance" of empathy with a boxer who allows himself be pummeled in a scene that evokes the Crucifixion. Hazel doesn't share the fascination with blood and martyrdom, but she witnesses it without judgment — much, it must be said, like a writer.

Because she sees through the roles that people play to their true feelings, Hazel is also a mirror. Practicing a duet with her, a high school bandmate suddenly grasps that he doesn't have to be the school's golden boy: "I felt relieved of something heavy I hadn't realized I'd been carrying."

When they communicate with Hazel at all, people communicate with an immediacy that changes them, and readers may find themselves reacting similarly. Huddle conveys Hazel's radical empathy and honesty without sentimentalizing or sanctifying them, often by means of tart humor. The book is full of quotable lines: "She's always suspected that if another person could truly see her, that person might just start puking."

As a portrait or life story, this novel-in-stories doesn't always cohere. After the chapter devoted to John Robert's birth — which Hazel greets with pure, rapturous love — we learn little to nothing about how his presence affects her subsequent life. A trauma that occurs relatively early in Hazel's life is unveiled relatively late in the narrative, with no discernible foreshadowing. The book is studded with odd little anachronisms: a reference to Star Wars in a chapter set in 1957; a mention of Hazel's distaste for Tea Party Republicans in a chapter set in 1982.

But these are quibbles, given how entertaining, thought-provoking and surprisingly relatable Hazel is. In just short of 200 pages, Hazel Hicks makes an indelible impression on us, raising all sorts of questions about what it really means to be alone or insignificant or "plain." Looking at photos of his aunt, John Robert sees something "appealing" that isn't conventional beauty or charisma: "It's almost as if she is perpetually refusing the categories of plain or shy or low-profile or no personality — at the same time she's sort of defending women who might have been assigned to such categories."

If those categories seem retro in 2019 — when the internet has taught us how absurd it is to glance at someone and decide she has "no personality" — Hazel reminds us that carving out one's own identity is not a new thing. Just a brave one.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.