- Matthew Thorsen

- Huck Gutman

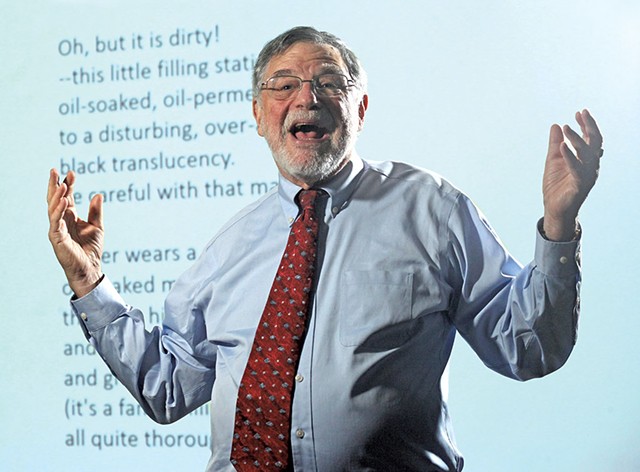

Huck Gutman stands before his American poetry class, which fills maybe a quarter of the large, sterile lecture hall in the University of Vermont's Waterman Building. Before he speaks, he scans the collection of students scattered across the tiered, harshly lit white room as if sizing them up: the attentive retiree in the back row; the eager female English major up front; the burly, bearded young man in a military tee sitting by himself to the side; the trio of skinny, slack-postured guys in the middle of the room; the loner in the back who never lifts his gaze from his laptop.

Gutman, clad in a dark suit and tie, steps forward. A light buzz of chatter ebbs, and class is suddenly in session.

"None of you wrote to me," Gutman says with his arms wide, a maudlin mix of sadness and surprise in his voice. The professor is big on repetition, so he repeats himself: "None of you wrote to me," he says again, this time adding a tease: "which makes you really dumb."

Any experienced performer knows the importance of pausing to allow your audience time to react. Gutman is silent as nervous and confused giggles titter around the room.

"But," he says, striking an exaggerated professorial pose as he raises a pointed finger for emphasis, "You are not as dumb as me. My stupidity overshadows yours."

Normally, such a confession from a man like Gutman might be specious, given that this is a sophomore-level English class and he is, well, Huck Gutman. The 73-year-old has been a fixture in the UVM English department for 46 years. He's the recipient of two Fulbright teaching scholarships, as well as a pair of top teaching awards from the university. He serves on the board of the Vermont Humanities Council.

Gutman is also close friends with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and cowrote the democratic socialist's 1998 autobiography, Outsider in the House. He later served as Sanders' chief of staff in the U.S. Senate.

In short, Gutman is a brilliant man. But even brilliant people occasionally stumble. And sometimes, how they handle those stumbles is key to understanding their genius. Such as, for example, when a widely admired professor accidentally omits an entire section from a coursebook that he created.

The course, called "The American Poem," is a survey course on the greatest U.S. poets of the 19th and 20th centuries — the greatest in Gutman's not-inconsiderable estimation, anyway. Today's class was to begin with a section on Elizabeth Bishop, the Massachusetts-born poet who died in 1979. Gutman, however, had neglected to include works by the Pulitzer Prize winner and onetime U.S. poet laureate in the book he personally curated for the course. He hadn't caught the error until now. If any students caught it, they didn't say anything. Whoops.

Improvising with the confidence that nearly five decades of teaching experience affords — or maybe just stalling to allow his teaching assistant time to hand out copies of Bishop's poems — Gutman pirouettes, poetically speaking.

"Who dressed up for Halloween a few nights ago?" he asks. A smattering of hands goes up. This question leads to a brief discussion of the power of escapism from the mundane and ordinary, which leads to a detour into poet Wallace Stevens and what he termed "the malady of the quotidian." And that discussion somehow segues seamlessly to Bishop and her poem "Filling Station," a work that revels in small, mundane details — a dirty dog, a greasy wicker sofa, a "big hirsute begonia."

At the end of the poem, in which Bishop ponders a small, family-owned gas station, the people who live there and those who pass through it, she concludes, "Somebody loves us all."

In reciting it, Gutman lets that last line hang in the room like a hug that lingers a second too long. He pauses for several moments before engaging the class again. He asks not what the poem means, exactly, but what it makes the listeners feel and think. Along with dramatic flair, this is a Gutman specialty: coaxing students into functional relationships with poems.

"He, for me, is the model of the good kind of teacher," says Mary Louise Kete, an associate English professor at UVM and, in the mid-1980s, a student of Gutman's herself. "He never wanted to force people into a Huck Gutman kind of interpretation of something. He wanted people to come up with a relation to literature that mattered to them."

"The problem with the way poetry is read in middle and high school is, they seek specificity about poems," Gutman tells this reporter after class. "It's more useful, I believe, to think of poems as conversations. At their best, there can be a dialogue with poems. Sometimes we can speak back to them."

Gutman has been leading those conversations and speaking back to poems — often in an animated, loud fashion — at UVM for close to half a century. But next semester, spring 2018, will be his last. Gutman's retirement will leave a sizable void, not merely because of his tenure's length, but also because of the singular style, knowledge and experience that leaves with him.

"It's a real loss for the department," says UVM English professor Tony Magistrale by phone. "He's been the historical beacon," he continues, speaking to Gutman's institutional knowledge of UVM as a place of higher learning as well as what a professor's role there should be. "He's a reminder that this is the path we've chosen, and we need to make the most of it."

Gutman's path has taken him from Waterman to Washington, D.C., and back again. And he has certainly made the most of it.

I Celebrate Myself, and Sing Myself

- Matthew Thorsen

- Huck Gutman in his office

"I don't think I ever go into a class and talk about meanings of poems," Gutman says, hunched over a paper cup of coffee in Waterman's gloomy basement café. He's speaking about his approach to, and feelings about, poetic interpretation: what it all means, man.

"I just don't think poems are carriers of meanings," Gutman continues, raising his gaze from his coffee to reveal bright, inquisitive blue eyes. "They're things we make, and, like a song, like a piece of pottery, like a computer program, they do things, and we can marvel at what they do."

For Gutman, poems do quite a lot. He's spent his entire adult life marveling at them and, just as passionately, trying to share them with others.

"To me, poems are utterances, speaking meaningful and important things that we don't usually say to one another in the course of our daily lives," he says. "But do they mean things? I dunno. I think that's a bad alley to go down."

So he rarely goes. Earlier that afternoon, when teaching another Bishop poem, "At the Fishhouses," he confessed two things to the class: "I'm not big on literary allusion," and "I don't understand this poem."

But comprehension, or lack thereof, didn't diminish his enthusiasm for the piece. If anything, not understanding it only deepened the excited fervor with which he pulled it apart, line by line and rhyme by rhyme, for the class. That excitement may well stem from his belief that poetry is particularly effective at inspiring us to think about things most of us don't understand — or talk about.

"It's surprisingly seldom that we talk about love and death, who we are, and what we aspire to be. We tend to talk about sports and weather," Gutman explains. "That's why I like teaching poems: I like the fact that they talk to me about who I am but also about [the poet's] otherness and how there is a duality in them."

Students past and present say they respond to Gutman's ability to chisel away the academic artifice around poetry and make it more accessible.

"In high school, we're always told there is a meaning to poetry, a right or wrong answer, and it's really intimidating: Somebody knows the right answer, but I don't," says UVM English major Anna Gibson, a current student in Gutman's American poetry course. It's her fourth consecutive semester with the professor.

"Huck has always emphasized that the poets are trying to say something and has taught them in a way that is a lot more accessible and a lot more sane than anyone had taught them before," continues the junior from Charlottesville, Va. "It opened up a world of conversations that I could be having with these writers."

"He teaches that poetry speaks about things that people are often silent about — insecurity, our shame or joys. Poetry speaks to all of that," says another current Gutman student, Carol Clay. "It's a way, if you slow down, that you can learn more about yourself. And he's very good at facilitating that."

"I think that's what poets do," Gutman says. "They remind us of ourselves and what we might say if we only had the words or attentiveness."

Clay, 68, is a retiree from Charlotte who frequently takes courses at UVM. She signed up for Gutman's class after meeting him at a dinner party, where she told him how "cool it was to [sit in on] classes for free when you're older." Through the university's Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, Vermonters 50 or older can take UVM courses gratis. Gutman's wife, Buff Lindau, is also taking the poetry course.

Clay is a self-described "science person" who's also keenly interested art history. It's unlikely she's encountered many chemistry or art professors who lead a class with quite the same theatrical flair as Gutman.

"He's a great ham," says Clay. "He needs to be onstage."

Stories approaching legend abound on Gutman's dramatic prowess in the classroom. Perhaps the most famous is how he teaches "Song of Myself" by Walt Whitman — a particular Gutman favorite. The professor is said to lie on his back on a table or desk, silent and motionless, as students file into the classroom. Then, just as they begin to wonder what's going on — or whether Gutman is still alive — he springs to life on the poem's first line: "I celebrate myself, and sing myself."

"Whitman is not meant to be read quietly," observes Magistrale. "It's meant to be shouted with a bodic yelp."

Magistrale is a longtime friend and colleague of Gutman's and co-taught a large English literature course with him for a decade. He specifically remembers Gutman's lectures on Whitman. "He would do a whole week on 'Song of Myself,'" he recalls. "There was lots of drama in his reenactment of the poetry. It was a treat to watch him."

Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" is another of Gutman's greatest hits. But that one requires audience participation. Specifically, all of the students take turns reciting individual lines from the epic poem and are encouraged to do so with feeling.

"Huck felt really strongly that this was a poem about Ginsberg's anger, and he wanted us to yell," says Clay. Perhaps owing to nerves, the students didn't. So Gutman did.

"This scream comes out of nowhere that you can hear down the hall," remembers Gibson. "You can't get bored in that class."

The Flag of My Disposition

- Matthew Thorsen

- Huck Gutman

Whitman's "Song of Myself" is a cornerstone of modern American poetry. But it's possible that Gutman loves it for another reason: The poem's opening stanza bears an uncanny similarity to how he came to be known as Huck.

At the start of Whitman's poem, the poet is lazing barefoot in the grass: "I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass."

At the start of his career in academia, undergraduate Stanley Gutman was similarly enjoying a leisurely day in the grass — he was drinking wine, barefoot, on the green at Hamilton College.

"A friend said I reminded him of Huck Finn," recalls Gutman, smiling. "And the name just sort of stuck."

The nickname undoubtedly suits him. However, if a writer penned a novel set at an imaginary university that featured an enigmatic American lit professor named "Huck," academics at actual universities might well deem that author a hack. The heavy-handed nod to Twain would simply be too much.

Even less believable, perhaps, is the tale about a free-spirited intellectual called Huck who ends up moving from a rural state to Washington, D.C., as the right-hand man and trusted confidant of an influential U.S. senator. Yet that story is true, too.

Gutman says he was involved in the civil rights movement as an undergrad and later as a graduate student at Duke University. He befriended Sanders after he took a job at UVM in the early 1970s. The two remained close throughout Sanders' political ascension, from Burlington mayor to congressman to senator.

Gutman took an unpaid leave from UVM in 2006 to serve as the senior policy adviser in Sanders' Senate office and became his chief of staff in 2008. He held that role until 2012, when he returned to teaching at UVM.

"Surprisingly to me, my teaching and poetry life doesn't intersect that much with my political life," says Gutman. "I don't get much benefit from the political dimensions of poets."

But at least one colleague thinks there is a significant connection between Gutman's two worlds.

"I see a real correspondence between his love for Walt Whitman and his love for Bernie Sanders," says Phil Baruth, a fellow UVM English professor and a Vermont state senator (D/P-Chittenden). "Huck listens to Bernie Sanders and hears the poetry in what he's saying and feels it in a really powerful way. And he has found unique ways to translate that to the world — much like when he reads Whitman and experiences it on this visceral level, then turns around and projects that to listeners.

"So, I don't think you have a Bernie Sanders or a Walt Whitman without people like Huck, who are able to bring that message to others," Baruth concludes.

Still, Gutman sees his interests in politics and poetry as parallel, not intertwined. However, he has employed poetry in his political life.

A Vermont progressive inside the Beltway, Gutman was an outsider of almost comic proportions. He was chief of staff to the only independent in the Senate, one of the most liberal lawmakers in Washington. Beyond that, Gutman was a sixtysomething poetry professor holding down a gig typically filled by younger career political types. To avoid suffocating in such an insular environment, he turned to poetry.

In a 2010 Washington Post story, writer Manuel Roig-Franzia chronicled how Gutman "began lobbing poems into the email inboxes of every chief of staff in the Senate."

Once a month, he would send a poem to an email list that included staffers, politicians and academics around the country. By the time Gutman left Washington, that list had grown to more than 1,500 addresses — it's still active, though Gutman says he hasn't sent anything in a while. Along with poems by the likes of Emily Dickinson and Pablo Neruda, he would include detailed, glowing analyses of the sort his UVM students would surely recognize.

"Bernie Sanders is not your average U.S. senator, and Huck Gutman is not your average chief of staff," Luke Albee told the Post in 2010. Albee served as chief of staff for Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and, later, Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.); he's now senior adviser for Engage Cuba. His late father, George Albee, was a psychology professor and colleague of Gutman's at UVM.

"Huck was a unique chief of staff who was not cut from the same cloth as other chiefs," Albee tells Seven Days. "He was an acquired taste, but he was a taste everyone fell in love with. He could be a contrarian and represented Bernie's views well — he just did it with a little more sunshine and a smile on his face."

"He was sort of an avuncular Renaissance man roaming the halls of Congress," says Bob Rogan, chief of staff to Congressman Peter Welch (D-Vt.) since 2007. Rogan says he and Gutman met regularly during their overlapping time in D.C., sometimes to talk shop but more often to chat about family and the stresses of living in the nation's capital.

"Huck was effective because he cultivated relationships and built bridges by raising the level of dialogue above the drumbeat of the daily political and policy machinations," says Rogan. And, he adds, there was another reason Gutman was good at his job.

"His secret weapon was his love of poetry and the arts, which he wielded regularly in service of Bernie's agenda by reminding us of our common humanity," Rogan says. "In today's hyper-polarized environment, we could use a lot more Huck Gutmans down here."

Sanders' office didn't respond to inquiries about Gutman.

"There are whole dimensions to who we are that don't get touched in the kind of political discourse that goes on in Washington," says Gutman. "What I think poetry does is remind us that, as human beings, we are larger than just political creatures. And that's why I started sending poems out. Because I think people living inside the Beltway were in great need of that."

I Stop Somewhere Waiting for You

Speak with Gutman for practically any length of time, on any subject, and he's bound to reference at least one great writer and probably several. Talking about the intersection of politics and poetry, for example, he digresses to recite lines by Ralph Ellison, Jonathan Swift and William Wordsworth in a span of roughly three minutes. In fact, an average of one sharp literary reference per minute seems about the going rate for Gutman.

"He's very tangential," says Clay, the senior student in his American poetry course. "He's memorized hundreds of poems and will burst out with them at any time. But it's not disorganized; it's perfectly off-topic."

That tangential quality is likely the product of a mind that never stops processing information. It also reflects the personality of a born teacher who never stops wanting to share what he knows with those who want to learn.

For his final UVM course next semester, though, Gutman is indulging himself. Inspired by a formerly outgoing colleague (who then decided not to retire), he's teaching solely on the poets who have inspired or spoken to him personally. Think of it as Huck Gutman's Greatest Hits.

"Yes, that's exactly it," says Gutman with a chuckle. "Some of them are great poets; some are maybe not-so-great poets. Some write in English; some write in other languages."

"I want to sit in on a couple of those classes to hear him do a couple things," says Magistrale. "I want to hear him do Emily Dickinson one more time. It's like [Led Zeppelin's] 'Stairway to Heaven.'"

When the classroom door closes on Gutman's last UVM performance, however, it's unlikely to mark the end of his teaching career. He speaks regularly at libraries as part of the Vermont Humanities Council lecture series and plans to continue. He also plans to remain on the board of Our Revolution, the political action group that grew out of Sanders' 2016 U.S. presidential campaign.

"I think there are some wonderful people who get older and realize they're handing down the world to a younger generation and think they should leave it in as good a shape as possible, and then just leave it," Gutman says. "I'm not sure I'm in that group. I'd like to be involved. I'd like not to be on the sidelines looking at this strange spectacle of life."

"Huck is fundamentally an optimist and really thinks things could be better," says fellow English professor Kete. "And he's impatient with people who think things just have to be. He really believes that what we do is important. He walks the walk."

Gutman also wants to keep talking to people about poetry but without the structure and rigors of academia.

"I'd like to talk about poetry in prisons," he says. "If I think poems can speak to middle-class students and older people, then I think they can also speak to people that society pushes to the margins."

The section heads in this story are lines from Walt Whitman's poem "Song of Myself."

Correction, November 29, 2017: An earlier version of this story misidentified Elizabeth Bishop's cause of death.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.