"What does nature mean in the 21st century?" wonders Wadham, New York, poet Chuck Gibson. "Many people claim to 'love nature.' What does that mean?"

For Gibson, "nature" means his home and the setting of his work, the vast tract of legislated wilderness we face when we gaze across Lake Champlain. While "Vermont has much more of a human touch," he says, "the Adirondacks represents Nature in the raw. It represents a special opportunity for a creative artist to dig a little deeper into 'nature' than someone writing from a more settled place."

Ra Press founder Dave Donohue agrees: "I think we've been overmedia'd the last three decades, to the point where we've lost the ability to appreciate nature. Living in the Adirondacks helps us hold onto this gift." This land of rugged primeval mountains and pine-darkened lakes, where Emerson and William James communed with nature, seemed to Donohue like a pretty good place for a group of friends to try an experiment with literature in the raw.

Ra has no office beyond a post office box in Ticonderoga, no full-time employees or marketers or printing presses on call. Donohue and friends produce the small, soft-cover books themselves with the help of home computers and a Middlebury stationer who gives them advice on art and type formatting. Binding happens on the living-room floor. "Ra Press is a cottage industry in the most extreme sense of the word," says Donohue, "as these books are assembled in our home."

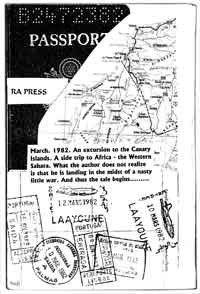

Ra is the Egyptian god of the sun, a name Donohue chose in honor of his first title, a travel tale of Alexandria. At first glance, the books may remind you of your high-school literary magazine. But their low-tech design betrays more sophisticated influences. "I wanted to have that mid-'60s City Lights Beat style," Donohue says, referring to the famous San Francisco bookstore. "No gloss, no glitter -- I wanted the books to be intimate, accessible, inexpensive, totally eccentric, and 100 pages or less."

Ra started as a self-publication venture for Donohue while he was teaching in the Middle East and then working at Essex County ARC, an organization that serves the developmentally disabled. At ARC he met fellow writers Gibson and Mary Randall and invited them to add to his list. Over Thanksgiving dinner, he "challenged" his sister-in-law Joan Frost to let him publish some of her poems, and so the Ra collective was born.

Despite their rural setting, the Ra writers aren't "outsider artists," blissfully indifferent to the nitty-gritty of the book business. Most have been writing actively since their college English-major days, and some have endured frustrating experiences with major publishers who were interested in their work -- but not interested enough. Donohue recalls the New York agent who nearly sold his first novel, then absconded with the manuscript in tow.

Publishing your own works on a shoestring budget is a way to take control of that process, even if it means giving up some of the potential rewards. Donohue's unofficial slogan is "books that make a point, not a profit." Currently, all 11 Ra titles can be found at In the Alley Bookshop in Middlebury's Frog Hollow, but the individual writers are responsible for distributing their books farther afield. Some titles are available at area bookstores, including North Country Books in Burlington and Cornerstone in Plattsburgh.

The press' offerings are unabashedly eclectic, defying the marketing categories that segment so much of contemporary literature. Here you'll find Adirondack-themed fiction alongside more exotic travel pieces, and short stories sharing a cover with poems.

Acknowledging that many readers see prose and poetry as forms that don't mix, Donohue counters, "For me they should be interchangeable. Ray Bradbury's prose is lyrically beautiful. Henry Rollins' poetry reads more like short stories."

The mixture works in Mary Randall's The Ghost of Starbuck-ville Dam. The title story is a coming-of-age tale whose setting, a desolate Adirondack summer house, seems to invite gentle visitations from the supernatural. The short poems that follow speak in a more personal voice but return to the central mystery of the story: "love, and the funny places where it may be found."

In five moving yet fiercely unsentimental lyrics, Randall describes raising a daughter born "retarded... with eyes of sapphire blue" who ends up being her mother's "masterpiece,/my fist in the face/of the world." Other poems transfigure ordinariness as they sketch in spare, evocative detail what it's like to live in a rural town among "deli girls" and "wordless brutes," sometimes fighting and sometimes embracing a life that feels like "a laundry load;/Cycles of clean and dry and sweat/up and down the basement steps."

A work that leaves the Adirondacks far behind is Donohue's memoir, El Ayoun: Reflections in a War Zone. From a comfortable barstool in the Canaries, the author-narrator lets curiosity draw him to the edge of an ugly conflict between the Moroccan Army and a group of rebels contesting a chunk of the Sahara. Though nothing much happens, the tale benefits from its juicily nightmarish premise: The narrator chooses his destination blindly, only to find his passport confiscated at the airport and the natives of El Ayoun dissolving in helpless laughter at the notion of a tourist in their bleak garrison city.

Donohue's narrative suffers from baby-boomer self-consciousness and a tendency to make everything a bit too explicit, especially the browbeating of an American faced with the squalor of the Third World. The black humor of the book needs a lighter touch. But El Ayoun achieves eloquence in passages where the city seems to mirror the narrator's own alienation. "The wind and darkness still reigning outside, I heard the muezzin's call to prayer and, at that moment, could identify my isolation. It was the Muslim night, the feeling that if God could only care, he would."

We return to less alien but no more comfortable climes in Gibson's Seven Storms, a poem-cycle with illustrations by his daughter that follows the transformation of the Adirondack landscape from spring to spring. Gibson writes about nature using rhyme and meter, a traditional approach that might lead readers to expect the verbal equivalent of a pastel Thomas Kinkade woodland scene. Nothing doing.

Nature in Seven Storms is ferocious, majestic, wantonly destructive, occasionally gentle and almost never pretty. The forest teems with spectacles of natural decay, like the woodpecker tree revealing its "dark holes/ With their glimpses into a dark world cold/Canyonland of hoodoos leaf litter twigs..." Just when June arrives with its "new world of light-green leaves," making the poet wonder if Nature is a doting mother after all, "bugs like sand land on his ears/And bite his neck where sweat has pooled./It's possible that he was fooled..."

Fickle and untrustworthy, nature refuses to be ignored by human beings. The transition from winter to spring is happening inside us as well as around us:

New warmth will make us grow, outgrow

The frozen pools within we know

So well. [...]

The dreams that drifted under sifted snow,

Do they return or must we let them go?

These are themes that hark back to Robert Frost and the Romantic nature poets of the early 19th century. But Gibson's style is more playful. Sometimes it has the simple swing of children's verse: "If the snow/Must be seen/Let it show/Through a screen." At other times it thickens with its own storms of alliteration and internal rhyme: "Words unspoken broken flow/Where the waters wind below..." "Scary sky stretched tight as drum./Drum rolls loud. Bell rung. Bang come." This is good stuff to read aloud, though you may get your tongue twisted in the process.

Gibson acknowledges Dr. Seuss as an influence. "If children love wordplay, why not adults?" He feels that rhyme can help bring readers back to poetry, dispelling the notion that verse is a joyless high-art form. "There's a quirkiness to rhyme -- it brings in wordplay -- it answers questions in unexpected ways, it surprises. Free verse used to be radical but now too much of it is boring, just lying there. Poetry should hop and bounce, occasionally popping us between the eyes."

Keeping the reader off-guard seems to be part of the modus operandi of Ra Press. Its other offerings include Joan Frost's Concentric Circles, a collection of poems with a feminist slant; five more works by Donohue; and two lurid Adirondack-set tales by the "reclusive and somewhat mysterious" Jack Le Brun. Because the press' list is so varied, these are books to browse until you find the one that speaks to you.

Ra Press embodies a do-it-yourself literary ethos that's as much at home in the Adiron-dack backcountry as it ever was in Haight-Ashbury or Greenwich Village. Gibson captures its raison d'être, that writers have to write first for themselves, when he says, "Some people like to mess around with carburetors. I like to mess around with words."

All titles can be ordered from Ra Press, P.O. Box, 51 Ticonder-oga, NY 12883. Priced at about $9 each.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.