- Courtesy Of Lucie Whiteford

- The Highland Weavers at the Shelburne Museum, circa 1991, from left: Robert Resnik, Tim Whiteford, Lucie Whiteford and Marty Morrissey

The traditional Irish folk tune "Work o' the Weavers" honors overlooked textile workers whose efforts clothe people of all stripes. It echoes the tradespeople's quiet dignity, highlights their versatility and underscores their value.

The chorus proclaims, "If it wasn'a for the weavers / What would you do / You wouldn'a hae the cloth made oot o' wool!" It reminds us not to take anything for granted, even items most utilitarian and modest.

Friends of Marty Morrissey (May 7, 1938-March 30, 2021) describe him much like the aforementioned work of the weavers: quiet, unassuming and unwaveringly reliable. He was a founding member of the Vermont-based Irish folk trio the Highland Weavers, which began performing in the 1980s. The group was known for rousing, timeless Irish folk music, like the songs on its 1998 album Work o' the Weavers.

Though he was in excellent physical shape and otherwise in perfect health, Morrissey was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma in early 2021. By March, he had moved into hospice care. He died on March 30, at age 82.

"It was just horrifying, because he was well, and then two months later he wasn't here anymore," said Joan Rising, his domestic partner for more than 30 years.

She met Morrissey while the two were working at George Little Press in the '80s. Morrissey, who was born in Essex, Mass., had moved to Vermont in the late '60s to work for the Burlington-based commercial printer. He stayed until the early '90s, when, according to Rising, he was forced out by new owners who dropped all the older, higher-paid workers to bring in younger staff that they could pay less. But this change prompted Morrissey to pursue music full time.

Morrissey was not known for flashy onstage antics or an outlandish personality. People remember him for his steady demeanor and quiet constancy.

"Marty was just this calm, even, level backdrop," said Marie Claire Johnson, whose late father, Tim Whiteford, founded the Highland Weavers with Morrissey. "He was just so easy to be around. He was sort of like a peaceful day in the park."

- Courtesy Of Robert Resnik

- Marty Morrissey at Ulster American Folk Park in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 2007

Tim and his wife, Lucie, noticed Morrissey's affable spirit when they first met him after moving from Illinois to Vermont in the early '80s. One of the Whitefords' top priorities was to find people who shared their love of Irish folk music.

"That was kind of our thing," Lucie said.

They found their ilk at a recurring jam session at the Champlain Mill in Winooski. Morrissey soon approached Tim about starting a band. Along with Matt Buckley, another session player, the three became the Highland Weavers.

"That was a dream come true for [Tim]," Lucie recalled.

Morrissey and Tim were the band's longest-serving members. Several people held the third slot in the trio, including Lucie and Johnson, but Robert Resnik did so longer than anyone. Resnik is the host of Vermont Public Radio's folk and world music radio program "All the Traditions" and has played in numerous bands and partnerships.

"He was my most problem-free bandmate," said Resnik of Morrissey. Aside from their work with the Highland Weavers, they released albums as a duo, such as 2009's Old & New Songs of Lake Champlain. Resnik estimates that in playing together for 35 years, they performed 1,000 shows.

"He was much more of a generalist than your average Vermont musician," Resnik said. "He was always learning. He was up for all kinds of experimentation and fun."

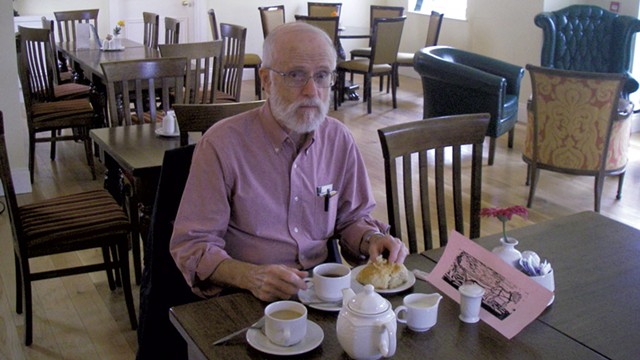

- Courtesy Of Robert Resnik

- Robert Resnik (left) and Marty Morrissey

Morrissey's love for Irish music and culture brought him, Rising and other friends to the Emerald Isle on several occasions.

"We walked into a bar on the Aran Islands, and everyone knew him," recalled Harriet "Happy" Patrick, a friend of Morrissey's for more than 50 years.

Patrick was one of the first people Morrissey met upon moving to Vermont. When Morrissey came to interview for a job at George Little Press, a mutual friend asked Patrick if she would board him during his sojourn. They remained close until his death.

"He was my dearest friend besides my husband," Patrick said. "He would listen to my tales of woe and tales of joy and never gave harsh opinions."

Johnson, also a musician, echoed Patrick's sentiment about Morrissey's listening skills. She grew up watching her father rehearse with Morrissey, listening to them play from her bedroom, well past bedtime.

"I feel like a lot of adults don't put much stock in what teenagers have to say," she said. "He never made me feel that way."

Morrissey was even-keeled yet full of vitality. An amateur tai chi enthusiast, he learned the practice at the Charlotte Senior Center and eventually led classes there.

"He had so much energy," Rising said. She noted his love of hiking and that he trekked the Long Trail piece by piece, completing it about a decade ago.

"Even as late as last summer, he was bounding up mountains," she continued.

Morrissey's friends recounted that his equanimity was not only his most distinctive quality but the one they prized the most.

"I probably saw him get mad maybe once or twice in my life," Resnik said. "He was just a sweet friend."

Rising added, "He was such a gentle, caring man. He never had a bad word to say about anyone."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.