- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

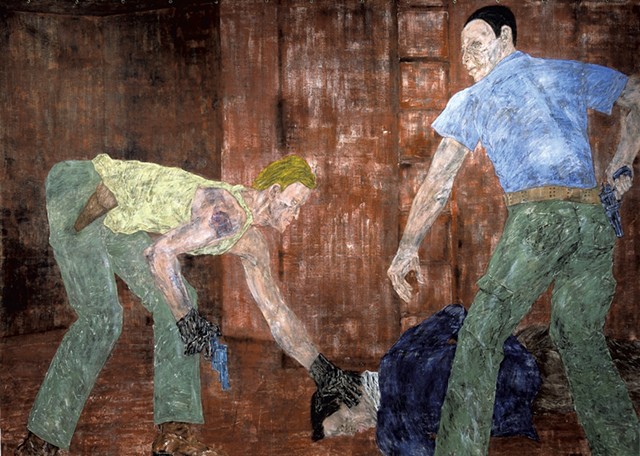

- "White Squad X"

On opening the door of the former cow barn at the Hall Art Foundation in Reading, a visitor is confronted — there is no other word — with "An Arrest," a 10-by-nearly-12-foot unframed canvas hung from grommets. The artist, Leon Golub (1922-2004), derived its subject from a newspaper photograph of the arrest of the Northern Irish politician John Hume by a British soldier in 1971, during the Troubles.

But Golub, painting in 1990, reworked the image into a Black man's arrest at the hands of a leering white man. The latter holds a gun at the head of his spread-eagled victim while pressing bodily against his back in a stance that threatens sexual violence. The terrified face of a third person, also Black, observes the action from the painting's lower left.

It's difficult to distinguish these larger-than-life figures from the room in which they're depicted: Both are painted in highly textured, predominantly ashen hues, as if violence is simply a part of the lived environment.

Visitors who follow the chronological path of the show from pole barn to horse barn to cow barn have received plenty of preparation for "An Arrest" in the form of the artist's earlier work. Yet, like school shootings, each instance of violence in Golub's work is a shock.

"Leon Golub" is one of two exhibitions at the Hall this season. The foundation, under Maryse Brand's direction, organized the show to reveal Golub's progression — a decades-long exploration of male abuses of power — in 67 works dating from 1947 to 2003. Approximately a third of the works are on loan from the Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer collection in Golub's native Chicago. The rest were collected by Andy and Christine Hall, on whose collection the Hall draws, along with the foundation's own collection, as sources for its shows.

"There is virtually no location where enormous types of violence have not occurred or are going to occur or are happening right at this minute," Golub once said, according to an introductory panel. (Aside from those panels, all the works' labels are accessible via QR codes, which also connect viewers to further information about certain paintings and media images from Golub's vast file collection.)

Golub's grim focus on violence was counterbalanced during his lifetime by his wife of nearly 50 years, the artist Nancy Spero (1926-2009), whose work addressed the feminist movement and celebrated women's gains. The couple shared a studio, collaborated and often exhibited together.

At the Hall, Golub is undiluted, and the artist's biography becomes a key to understanding his deep dive into depicting violence committed by men.

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation

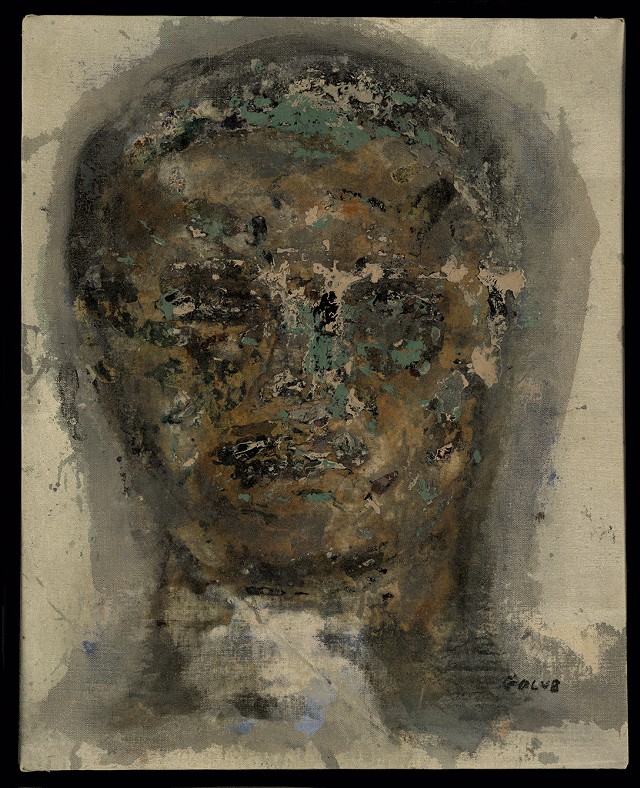

- "Head (XIV)"

Golub was the son of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine and Lithuania. An early encounter with Picasso's "Guernica," in 1939, gave him the idea of becoming an artist, though he started by earning his bachelor's in art history at the University of Chicago in 1942. Serving as a cartographer during the war, Golub encountered "firsthand witnesses and photographic evidence" of the Nazi death camps, according to a label.

Back from Europe, Golub changed course and earned a bachelor's in fine arts in 1949, followed by a master's in 1950, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The earliest piece in the show is a 1947 sketch on paper, "Skull," which depicts a squat, monumental male head reminiscent of the primitive Easter Island stone carvings.

Golub's early influences included African and pre-Columbian artifacts, classical sculpture he encountered while living in Italy, and the French artist Jean Dubuffet, who championed art by "outsiders" over academic training. Dismissing the American art world's veneration of abstract expressionism in the 1950s and '60s, Golub embraced figuration from the start.

His paintings from this early period are shown in the Hall property's pole barn. They explore male power in front-facing, static portraits that are punishingly scraped, such as "Head (XIV)" (1962), which depicts a Hellenistic head as mottled as a corroded bronze. It's a wonder such paintings aren't actually punctured, so gouged do they appear. Golub adopted his scraping technique from Dubuffet, eventually favoring a meat cleaver for the job.

The violence of Golub's technique and materials — including sketches in sanguine, a chalk or clay containing iron oxide or red ocher that is the color of dried blood — evolves into depictions of active violence starting in the mid-'60s. The Vietnam War was raging, and Golub and Spero, both lifelong anti-war activists, joined protests.

War, eternal and generalized, is the subject of the monumental "Gigantomachy III" (1966). On a 114-by-212-inch canvas, four men attack a fifth, who lies contorted on the ground, while a sixth runs by in the distance. Their whitish, practically flayed bodies resemble ghostlike afterimages, as if they are already dead, though each sinew and muscle stands out. The main attacker's foot and leg are oddly bent and enlarged, an awkwardness that somehow increases the visual impact of the violence.

"Gigantomachy III," in the former horse barn, is paired with Golub's 1970s acrylic portraits of male public figures on linen canvases roughly 20 inches square. These lesser-known works indirectly evoke more specific political violence. Developed from news photos, each of which is given a date in the title, the portraits depict a smiling Mao Tse-tung, an affable-looking General Augusto Pinochet and other powerful men — visages jarringly at odds with the destruction of human life for which those dictators are held responsible.

- Courtesy Of Hall Art Foundation/ulrich Meyer And Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection"

- "Gigantomachy III"

U.S.-sponsored state violence and oppression around the world, including in El Salvador and Iran, increasingly fuel the later works, in the cow barn. Most of these paintings, from the 1980s and early '90s, are gigantic, as if to mirror the scale of the damage. Yet they depict only a few figures caught mid-crime or in menacing poses — a reminder that, as in Golub's Mercenaries series, individual men carry out the work of the state.

These paintings are Golub's most realistic: The figures are dressed rather than looking like flayed nudes, trading weighted looks with each other and with visitors.

"White Squad X" (1986), part of a series that features a blood-red background, depicts a trio of men. One, blond and smiling, presses the head of a victim against the floor while holding a gun in the other hand; his partner, with back to the viewer, reaches for the gun at his hip and peers over his shoulder. That exemplary glance, implicating the viewer in the action, helps account for the horror that Golub's works inspire. Not only is the violence inescapable, larger than life, but the perpetrators' aggression reaches into the viewer's space.

In the 1988 documentary Golub, amid footage of the artist and his assistants on the floor scraping down "White Squad X" with meat cleavers, we hear Golub give his work an art-historical context.

"If you look at Renaissance art, medieval art, Assyrian art," he says, "it tells you a lot about who has power and who is getting the stick. It's a report. It's a report on how things are today."

Golub wanted his later work to be "reportage," as he called it, of American-sponsored atrocities. "Our foreign policy is that we subsidize actions like this in various parts of the world," he says in the film. "I would say virtually every country does things of this kind. And the most powerful countries do it the most.

"You know that old saying," he adds. "We've met the enemy and it is us."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.