- Courtesy Of Hood Museum Of Art

- "Ghostflower"

Readers who have visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in the past few years will know the name Kent Monkman — or at least recognize the look of his hyperrealistic, art history-informed fantasy tableaux. Two giant examples graced the Met's Great Hall from 2019 to 2022 and featured the Canadian artist's alter ego, a fit, long-haired, gender-fluid figure wearing nothing but a diaphanous red scarf and high heels.

Since completing those commissioned works for the Met, Monkman has been working on two more for the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. Those paintings, "The Great Mystery" and "Ghostflower," are now on view, along with two additional Monkman creations and a selection of works from the Hood's collection that inspired them. The show, "Kent Monkman: The Great Mystery," takes its title from the larger of the commissioned paintings, a nearly 10-by-8-foot canvas that easily commands the Dorothy and Churchill Lathrop Gallery at the top of the stairs.

From Manitoba, with mixed Cree and Irish heritage, Monkman uses his paintings to open conversations about colonial violence against Indigenous peoples — particularly in museums, which tend to exalt European and colonialist points of view. For the Met commissions, he studied works by 19th-century European and American painters in the collection, including Eugène Delacroix and François-Joseph Navez, and appropriated their iconic compositional and other elements for scenes that turn clichés about colonialism on their heads.

At the Hood, Monkman similarly interrogates canonical Western art, this time mainly drawing on mid-20th-century modernist and abstract works. His works hang beside the pieces from the museum's collection that inspired them, by Mark Rothko, T.C. Cannon, Hannes Beckmann, Fritz Scholder and Cyrus Edwin Dallin.

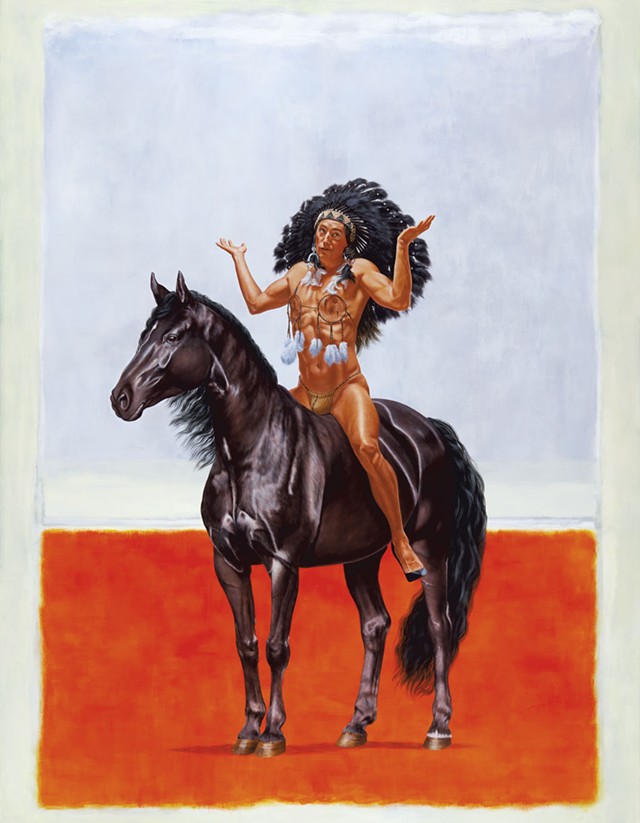

- Courtesy Of Hood Museum Of Art

- "The Great Mystery"

For "The Great Mystery," for example, Monkman recreated Rothko's 1953 oil "Lilac and Orange Over Ivory" in acrylics on a canvas of identical dimensions. Then he added his alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, atop a horse, a reference to Dallin's sculpture "Appeal to the Great Spirit." The collection's three-foot-high bronze statue of a Native man in a headdress on horseback is a 1922 cast of Dallin's 1912 statue that still stands in front of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Dallin's anonymous rider's head is thrown back and his arms outstretched in a pose that was widely understood at the time to signify the last gasp of a "dying" race. Monkman's Miss Chief, in contrast, sits upright with an expression and arm gesture that seem to say, "Guess what? We're still here!" True to her openly sexual name, which also plays on the words "mischief" and "tickle," she wears a "bra" made of dream catchers — the sort of humorous touch that Monkman is known for.

But the Hood's show does more than simply rewrite Western art, according to Jami Powell, the museum's associate director of curatorial affairs and curator of Indigenous art, who was surprised at the turn Monkman's art took with this show. The artist revisits his experiments in abstraction from decades ago and combines them with a new interest in the Cree concept of mamahtâwisiwin — a state of being connected to "the great mystery of the universe, the spiritual interconnectedness of all life, and unknowingness," according to the exhibition intro.

Powell, a member of the Osage Nation, has been following Monkman since her undergraduate days at the University of Denver, the curator said by phone. Like most curators of Indigenous art in the U.S., she studied cultural anthropology rather than art history, earning her doctorate from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Powell contributed an essay about Monkman to the Met show's catalog, interviewing the artist at his Toronto studio. She broached the idea of a Hood commission during that visit, she said.

Monkman's wide-ranging practice also includes installation, film and performance. He has been writing Miss Chief Eagle Testickle's memoirs, in which his alter ego enters a state of mamahtâwisiwin, with collaborator Gisèle Gordon. (The artist didn't grow up learning the Cree language but has been studying it with elders, Powell said.) Attempting a parallel exploration in his paintings, he found that his signature flamboyant realism couldn't capture that particular state of being — but abstraction could.

"Ghostflower" repurposes an abstract canvas that Monkman painted in 1997. Over the original painting's flat patterns in grays and browns, he painted Miss Chief in a position that appears to add depth: Floating in midair or lying down, her long hair rippling in one direction and a scarf in the other, she is shadowed by one of the flat, mothlike flower forms around her. The mystery of the universe is portrayed here as a state of suspension between two very different artistic styles.

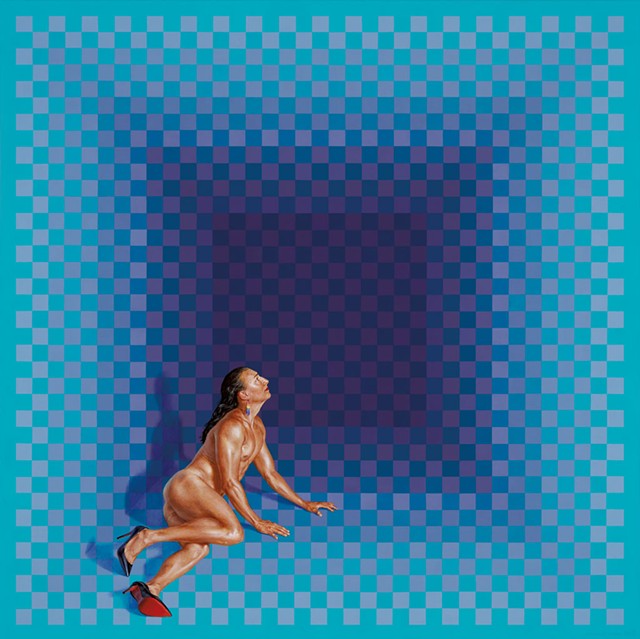

- Courtesy Of Hood Museum Of Art

- "Compositional Study for Muted Cell (Blue Light)"

Monkman borrows the geometric abstraction of Beckmann's painting "Muted Center (Blue Light)" for his identically proportioned, square-format painting "Compositional Study for Muted Cell (Blue Light)." In it, he places Miss Chief on the edge of an expertly reproduced version of Beckmann's concentric blue squares.

Echoing the longing posture of Andrew Wyeth's "Christina's World" from a different angle, the figure appears to be both looking toward the great mystery at the painting's darkening center and contemplating an implied prison cell that is the fate of so many Indigenous people. In the label, Monkman tells us that "In Canada, up to 90% of some prison populations are indigenous."

In that light, "The Great Mystery" has a further significance: That shrugging gesture Miss Chief makes atop her horse also refers to the hopelessly unbridgeable cultural gap between Indigenous people and colonizers. "For hundreds of years," Monkman says in the painting's label, "settler cultures have lived in relationship with indigenous peoples, yet we remain mysterious to each other, our core values too divergent to ever meld."

Monkman is no pessimist, though; he is also trying to convey "the commonalities in our understanding of the unknowable," as he puts it.

"He has this incredible ability to invite people into dialogue through his work, often around difficult conversations," Powell said. "He's such an incredibly talented painter; it's hard to turn away from his paintings."

Indeed, these works use humor, enormous technical skill and relatable realism to engage viewers of any background.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.