David Macaulay looks stumped. In the middle of a workday in early September, the author and illustrator of such famed works as Cathedral and The Way Things Work stands before a four-foot-long, hand-drawn blueprint of a steamship tacked to the wall of his home studio in Norwich. He waves his hands through the air in good-natured vexation.

"Never, in my experience, has that cliché of rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic been so appropriate," he remarks, cracking a wry smile. "That's what this feels like. I'm always rearranging illustrations, moving them around, and I'm not actually saving the ship, or saving the book, or clarifying the project for myself."

At age 10, Macaulay crossed the Atlantic on the steamship depicted in the drawing, when he emigrated with his family from northern England to Bloomfield, N.J. Nearly six decades later, he's built a career and an international reputation as the creator of best-selling books that explain architecture, engineering, mechanics and science with stunningly rendered drawings. His numerous awards include a MacArthur Fellowship and the 1991 Caldecott Medal for his illustrated storybook Black and White.

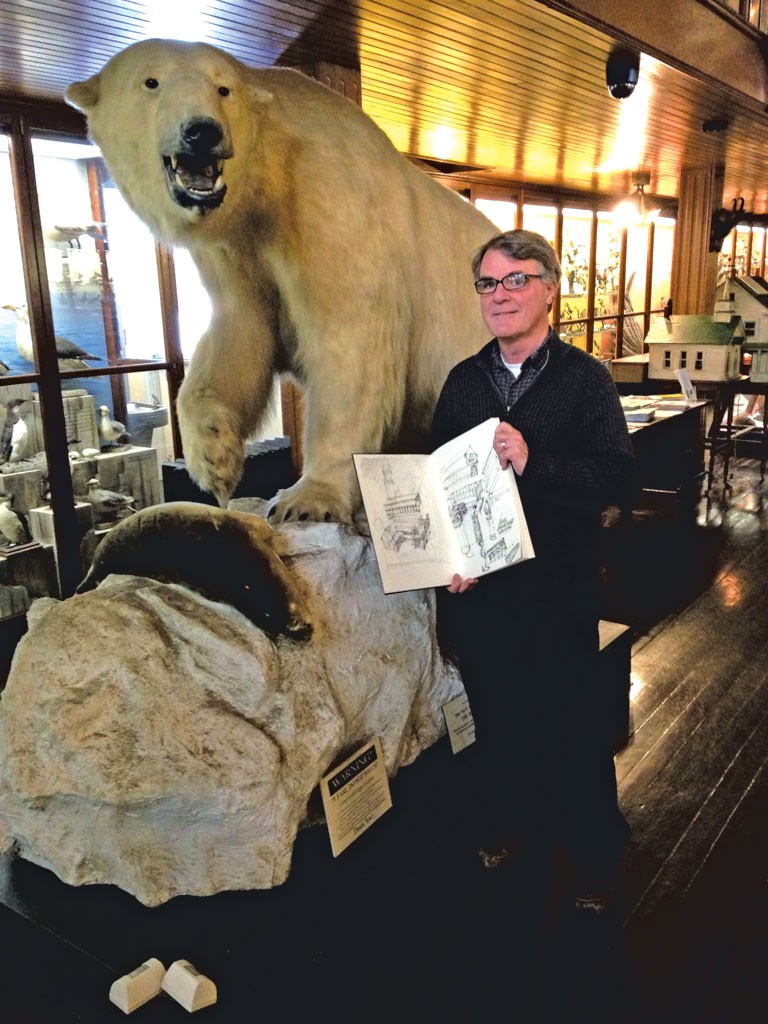

At the moment, though, Macaulay is four years into his new book project — "When did I hope to finish it? Two years ago!" — and seems to welcome the distraction of a visitor. Having wrapped up a several-months-long project in collaboration with the Fairbanks Museum called "Water Works: The Science Under St. Johnsbury," Macaulay has had little else to distract him from a seemingly unending, still-untitled story about the steamship on the wall.

"As I get older, the projects get harder," admits Macaulay. "What happens is that you become more ambitious; you try to do something you've not done before. You want to learn about something that is bigger than you probably should tackle, at least alone, so the projects take longer. And there's much more frustration."

Macaulay's early books, including Cathedral (published in 1973), Pyramid (1975) and Castle (1977), were stories with a single thread: "You start [the story] with flat ground and you end up with a pyramid or a cathedral," as the author puts it.

Those works drew on Macaulay's background in architecture. He has a bachelor's from the Rhode Island School of Design, but decided soon after graduating in 1969 that he had little interest in being an architect. Instead, he taught in public schools and worked for a design company before Cathedral's publication allowed him to devote most of his energy to writing and illustrating.

In 1988, though he had no formal engineering background, Macaulay illustrated Neil Ardley's 400-page, encyclopedic The Way Things Work. The introduction to engineering geared toward kids includes lots of playful explanations of levers, gears and belts, screws, pressure power, light, harnessing electricity, and much more. The book was immensely popular and catapulted Macaulay's career to the next level.

These days, Macaulay's book projects are about his own learning as well as the reader's. He spent years, for example, researching anatomy for The Way We Work, an illustrated guide to the human body. "I'd sit down in the evening after being there in the medical school or wherever I was, and try to draw what I'd learned that day," he remembers. "To see where I was, and how well I could really begin to understand the anatomical relationships between body parts — this joint with this muscle and so on."

For Macaulay, there's no better test of his knowledge than making a sketch: It forces him to think through the relationships among different visual elements, including their scale, mass and points of connection. "If you learn how to look at something, really look at it — and my chosen way is through drawing it — you begin to ask questions about how it really works," he says.

Take, for example, a toilet. Macaulay mentions that he might ask participants to draw one in two upcoming workshops for kids and adults he'll teach at the Fairbanks Museum later this month, in conjunction with "Water Works." "It's one of the most familiar objects around — everybody knows a toilet," he says. "But could you draw it? At what point would you stop and say, I'm not sure what happens back here, once it's underground and so on and so forth. At what point would you say, I don't know what's going on inside. How does it work?"

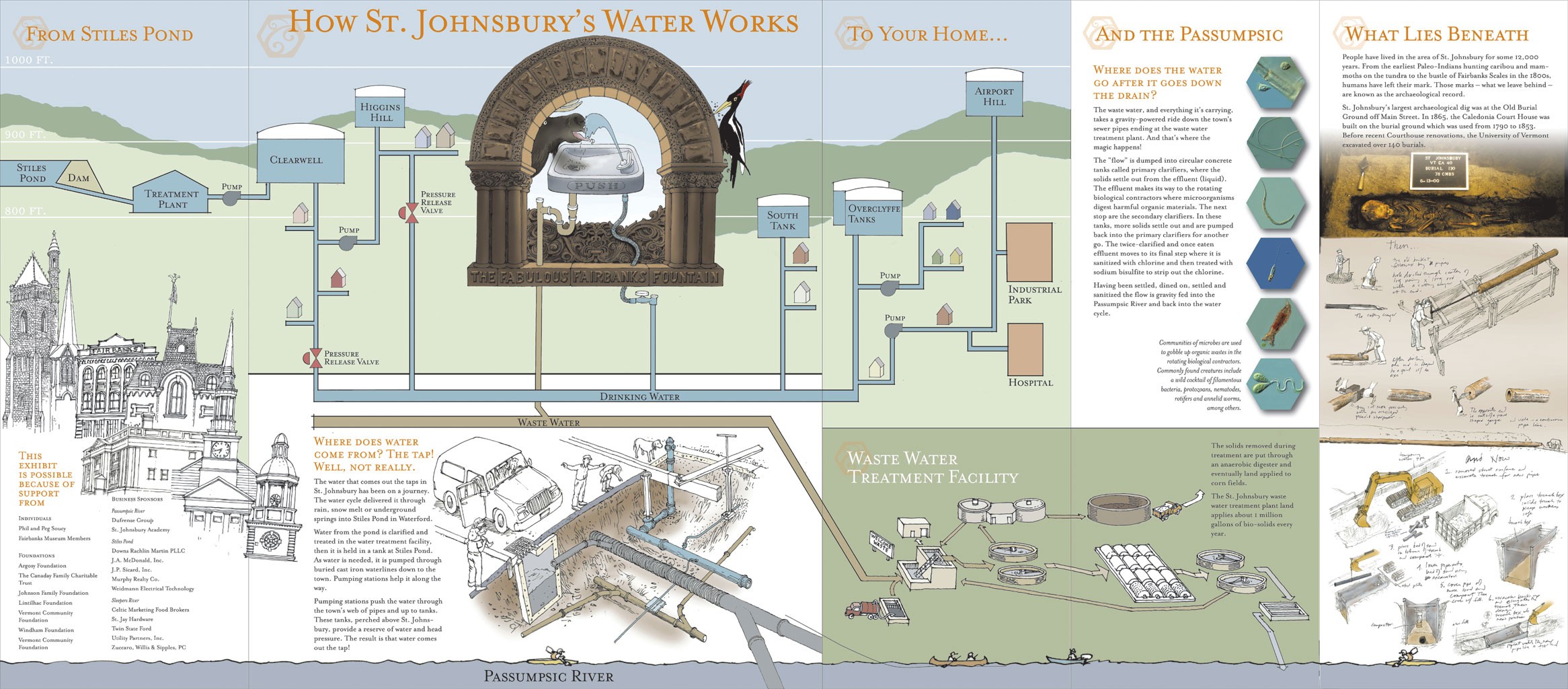

The toilet is a particularly apt example for those workshops, given the context of the Fairbanks' "Water Works" programming, for which Macaulay drew a large-scale illustration of St. Johnsbury's water system. As any recent visitor to St. J has noticed, long-awaited repairs to the city's underground pipes have resulted in a six-month-long construction project that has torn up the roads, including the main artery into St. J's downtown from Route 2.

"We formerly had a sewer system that combined wastewater and runoff," explains Adam Kane, the Fairbanks' executive director. "Basically, every time it rained, all that went to the wastewater system. And if it rained a lot, that untreated wastewater would go straight into the Passumpsic River."

Kane was just a few weeks into his job at the Fairbanks in August 2013 when he learned that the roadwork would be right in front of his museum throughout the summer of 2014. It was a potentially huge problem in terms of tourist traffic, but Kane chose to treat it as an educational opportunity.

"You have this infrastructure going in that's all about the environment, water quality, how you steward natural resources," he explains. "For the museum, which teaches all those things, we had the opportunity to talk about the importance of water to art and civilization; how fresh water is a resource that is in danger. We got to talk about engineering: Where does the water come from? You don't just turn on the tap and it magically arrives!"

For the water-system illustration, Kane reached out to Macaulay, whom he'd never met but knew lived just an hour south. The artist got on board right away. His family loved the Fairbanks, he told Kane; it was one of his son's favorite museums as a kid. Collaborating with the museum resulted in an additional exhibit, "The Way Macaulay Works," of the drafts and sketches that the author creates before arriving at his signature, neatly finished illustrations. Macaulay also made a detailed illustration of the museum itself, at Kane's request. It's worth braving the terrible roads to see both exhibits.

"It's such a throwback but with such great energy," Macaulay says of the Fairbanks. "It's a matter of connecting the old stuff with today and making it relevant, so you're not just going back and blowing the dust off. You're actually thinking about where you live, and ecology and all those issues that matter, just by looking at older things and having people that can interpret them in the light of now."

Though Macaulay's studio is decked out with several large monitors and a smattering of Apple products, he says modern technology doesn't pique his curiosity. "The problem with digital technology is that it's less self-revealing; everything's in a black box or behind a tiny panel," he points out. "In the old days, when you went into an elevator — you can still find them occasionally — it was a little cage, and you could actually see the counterweights going down. Now it's whoosh! Sixty floors in a minute and a half. You have no idea how you got there. And that's sad, because you're not encouraged to ask the question."

Which brings Macaulay back to his drawing of the steamship, about which he can rattle off a startling number of facts and stories. Name? The S.S. United States. History? Designed by William Francis Gibbs to beat the transatlantic speed record the ship was completed in 1952. Size? Nine hundred and 40 feet at its waterline, and built to house 2,000 passengers or 14,000 troops. Significance? Fastest passenger liner to cross the Atlantic, a title the United States has held since her maiden voyage on July 3, 1952.

The steamship project, Macaulay explains, "started out as a book about invention, and how one invention leads to another, and that kind of thing." Steam engines, for example, were originally created to power pumps that removed water from mines, where flooding was a constant danger. Over time, the technology was built on and improved, until a steam engine could power a passenger ship across the Atlantic.

Initially, Macaulay hoped to use the United States as an anchoring point to illustrate a larger concept of how simple inventions are developed by various hands until they evolve into having manifold uses. But as he delved deeper — including making two visits to the ship itself, now docked in Philadelphia — his curiosity led him to other storylines, including Macaulay's own foggy memories of his family's ocean crossing and the biography of the ship's designer.

Despite his current frustration with the project, "This is the most exciting part," Macaulay says, referring to the stage where he sketches up a storm and figures out what he knows and what he should keep questioning. "It's roughing it out. It's like carving something. Or like painting, and knowing when to stop. When you still have a kind of vitality; when it still has some life to it."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.