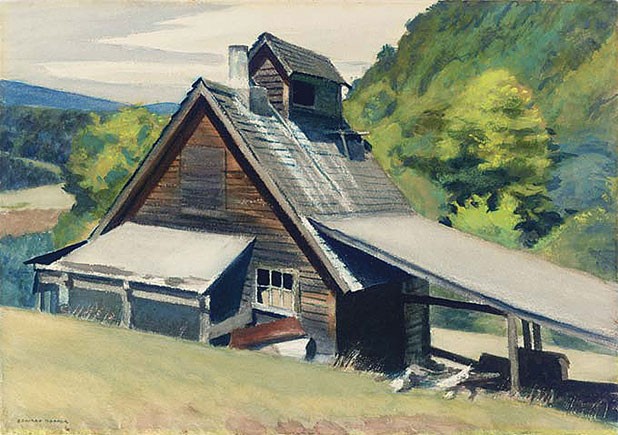

- “Vermont Sugar House,“ 1938

Edward Hopper’s time in Vermont was bracketed by natural disasters: the flood of 1927 and the New England hurricane of 1938. In between, the artist who would later become famous for scenes of urban isolation drew and painted agricultural buildings and rural landscapes. Viewing these works offers fresh insight into the psychology and evolving style of his overall body of work.

All of the 30 or so watercolors and drawings Hopper (1882-1967) made in Vermont are gathered for the first time in a show at the Middlebury College Museum of Art that runs through August 11. Several are on loan from Manhattan’s Whitney Museum of American Art, a leading repository of Hopper’s work.

The pieces are arranged chronologically, with ample annotations by Bonnie Tocher Clause, author of Edward Hopper in Vermont, a book published last year by University Press of New England. Clause not only studied these pictures closely, she tracked many of them to the exact spots where Hopper had made his sketches. Like the artist and his wife, the investigator and her spouse drove the back roads of central Vermont, searching for inspiring scenes.

It was Hopper’s practice, Clause informs us, to sketch from the backseat of his parked roadster. The 6-foot-5-inch artist was able to stretch out more comfortably there. That position affected his perspective in works such as “Three Mile Bridge,” a mid-1930s rendering of a span across the Winooski River that replaced a bridge destroyed in the 1927 flood. The height of the bridge’s steel truss is exaggerated due to the artist’s semi-recumbent position in the rear of his car, Clause notes.

Other observations of hers are less anecdotal and more enlightening. Hopper’s Vermont oeuvre can be divided into two distinct parts, Clause explains: the architecturally focused pieces painted during his initial day trips into the state from an artists’ colony in New Hampshire, and the landscapes composed during the summers of 1937 and ’38, when Hopper and his wife, Josephine Verstille Nivison, were agritourists staying at Wagon Wheels Farm in South Royalton. Clause finds the earlier pieces to be workmanlike in their execution, while the watercolors and drawings made a decade later are much more expressive, she points out, reflecting the self-confidence Hopper had acquired by then as a critically acclaimed and financially successful artist.

The trees in watercolors such as “Rain on River” (1938) are depicted by means of feathery brushstrokes. Here, too, the painter makes effective use of negative space, allowing an uncolored, thin length of paper to represent — appropriately enough — the White River.

Absence is a crucial element of Hopper’s vision. Some of his most famous oils of New York street scenes, such as “Early Sunday Morning,” are devoid of human figures. And even when people are present, as in what is probably Hopper’s most famous painting, “Nighthawks,” the mood is mournful, with onlookers’ attention made to focus more on what must have been lost than on what is silently present.

The same effect is achieved, less dramatically, in most of the Vermont works. The only living creature to be seen in the Middlebury show is a cow in an untitled watercolor from 1927. And notes of melancholy infuse the mundane scenes that the taciturn Hopper paused to paint during his wanderings up and down the White River Valley.

The landscapes are nevertheless alive with light and the forces of nature. The last piece in the show — “Windy Day” — shows an uncharacteristically bright-blue river chopping with waves as yellow-tinged trees bend and sway on its banks. Viewers may feel a tingle when reading Clause’s conjecture that this painting may have been composed on the very day that the great hurricane of 1938 was bearing down on Vermont. The Hoppers were known to have left the state precipitously that September, she points out.

The most rewarding items in the show may be its half dozen chalk and pencil drawings. The subjects are prosaic (for Vermont): barns, trees, distant mountains. But these sketches reveal the bones of Hopper’s art. They give insight into how his hand transcribed onto paper what his eye had seen. They may also serve as hors d’ouevres for the feast of Hopper drawings on offer this summer at the Whitney.

“Edward Hopper in Vermont,” paintings and drawings, Middlebury College Museum of Art. Through August 11. Info, 443-5007. museum.middlebury.edu

Bonnie Tocher Clause will give an illustrated lecture on her book, "Edward Hopper in Vermont," on June 7, 4 p.m. in the Mahaney Center for the Arts Concert Hall.

Hopper biographer Gail Levin gives an introduction to the artist’s work on June 27, 4:30 p.m., in the same location.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.