- Courtesy of John Huddleston

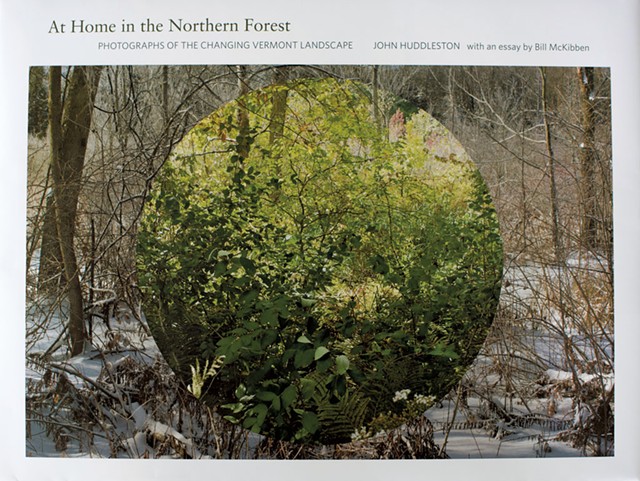

- "Snake Mt. Stream"

Almost every day for the better part of a decade, photographer John Huddleston took his camera into the woods around his home in Weybridge and tried to capture the subtle transformation of the forest. He would return to one spot over and over to chronicle the same view through different seasons; sometimes, he trained his lens on the ground, mesmerized by the chaotic accumulation of debris.

Huddleston, who taught visual art at Middlebury College from 1987 to 2017, has memorialized this slow documentary in his latest book of photography, At Home in the Northern Forest: Photographs of the Changing Vermont Landscape, a hefty 12-by-9-inch hardcover published in February.

"My vision is really sort of ordinary vision," he said. "It's not about looking for that culminating moment — like Ansel Adams and his grand landscapes, where God is in the landscape, or shining down upon the landscape, or something like that. Mine are much more matter-of-fact daily pictures, but there's something special about them, too, if you have the patience to look for it."

For Huddleston, ordinary does not mean uncomplicated. His images of stick-season hillsides look like a sea of barbed-wire brambles; his extreme close-ups of beech tree bark resemble weathered human skin. Seven Days spoke with Huddleston about seeing the world clearly, capturing the passage of time, and the difference between the mind and the brain.

SEVEN DAYS: You spent all these years walking in the woods around your house, taking pictures of a landscape that must be so familiar to you that you can mentally re-create it. What are the challenges of photographing a place you know so well? How did you know when you'd managed to capture what you set out to capture?

JOHN HUDDLESTON: That's on my mind all the time — how I might be misinterpreting or mislabeling things, or constricting things or solidifying things that really aren't solid at all, because everything is moving and changing all the time. That particularly comes to bear with trying to capture the sense of constant change in photographs of the forest.

- Courtesy

- At Home in the Northern Forest: Photographs of the Changing Vermont Landscape by John Huddleston, George F. Thompson Publishing, 168 pages. $45.

I think one of the very positive things about photography is that it teaches you to really look each time, to quiet your mind and perceive. If you don't, your photographs are going to be totally disillusioning, because when you go back to them, you'll realize that you were trying to capture what you were thinking as opposed to what you were actually seeing. This is a big life lesson that applies to lots of things, but photography can point it out pretty quickly.

As far as knowing when you've gotten the image, I think the success rate is pretty low. I took hundreds and hundreds of pictures to make this book. Most of them did not work out — I didn't get the right visual relationships, or it just wasn't compelling in the way that I wanted it to be. As a photographer, you're constantly reminded of how you're not seeing things accurately.

SD: Your book includes a series of composite images — single photographs of one location in the woods, overlaid with parts of other photos, taken in the same spot in a different season. How did you make those pictures?

JH: I probably went to the same spot 20 or so times and set up the camera in the same place. At first, I tried [arranging the images as] triptychs or quadratics, but those didn't really work, because the changes weren't integrated. I think the integration of these pictures makes the idea of change a little more forceful, a little more apparent.

- Courtesy of John Huddleston

- "Snake Mt. Pond"

I could have used Photoshop to make branches line up perfectly, but I didn't do that. I think that's part of what makes the images interesting — that they're reflective of these different times.

SD: There's something about the compression of all those images, captured at different moments, that mimics how we actually experience time — not in a left-to-right, linear progression, but as a layered accumulation of experience. Is that something you thought about as you created these?

JH: I think the pictures point to something I'm trying to work out, which is how the past and the future exist in the present. We're always remembering the past and projecting into the future; on an atomic level, things are changing from second to second. That fact is the present.

SD: In his introduction to your book, Bill McKibben writes that the "unintentional and mostly unnoticed renewal of the rural and mountainous East represents the great environmental story of the United States and, in some ways, the whole world." What role do you think art can play in shaping our response to the climate crisis?

JH: I hope my book can show people the value of the forest through the beauty that I find in it. In 1870, a little over 20 percent of the state was forested. The rest was cleared for farmland, which devastated a lot of species. Now, that balance has been reversed — today, 80 percent of the state is covered in forest. That regrowth happened largely because of human negligence.

- Courtesy of John Huddleston

- "Dead Creek"

We've got something so beautiful around us, and it's come back from this state of devastation not too long ago. And that same destruction could happen again. So I think we have to really value what we have, to slow down and see our connection to other entities on the planet.

Stephanie Kaza, one of the writers I quote in the book, talks about the inequality of the human voice over everything else. We don't hear the animals or the trees talk, but they have a right to exist as much as we do. It's our job to try to listen, to imagine what their needs might be.

SD: In your foreword to the book, you refer to the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who thought of the forest as an infinite space within the mind. You wrote: "This immensity is within us." What does that mean to you?

JH: Our minds are much bigger than our brains. In part from working on this book, I've come to think that we are so intimately interconnected with everything — and we're changing, too, like everything else is changing. So to think that there's this little concrete entity of "John" is kind of foolish, in a way. My mind is big, but it's not exactly John that's big: It's my connection to everything that's big.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.