- Sarah Priestap

- Illustrator David Macaulay in his Norwich studio

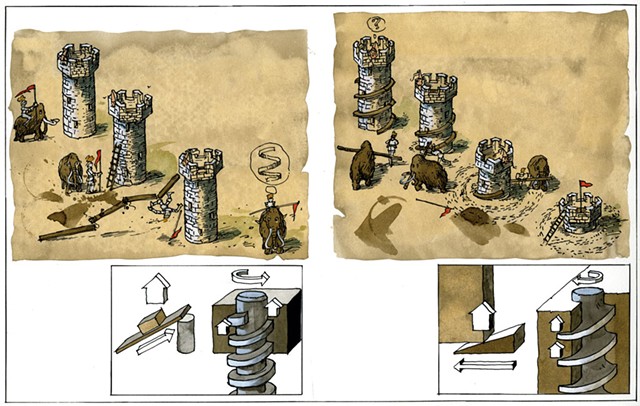

David Macaulay is renowned for his intricate drawings demystifying everything from how castles were built (Castle, 1977) to the inner workings of the brain (The Amazing Brain, 1984). But he may be best known for the comprehensive The Way Things Work, first published in 1988. A 1991 Caldecott Medal winner and 2006 MacArthur Fellow, the British-born illustrator, 71, has lived in Norwich for the past dozen years.

Now on view at the Vermont Arts Council's Spotlight Gallery, "Macaulay in Montpelier: Selected Drawings and Sketches" provides insight into the artist's meticulous work translating a variety of technologies and structures into visual form. In addition, Macaulay presents the lecture "Illustrating Architecture From the Inside Out" on Wednesday, October 24, at the University of Vermont in Burlington.

Seven Days chatted with Macaulay about his process and perfectionism and what he'd like to do next.

SEVEN DAYS: You've said you take a "draw 'til you drop" approach to your work. Can you elaborate on that?

DAVID MACAULAY: Most of the stuff I do is nonfiction, and that means I'm learning the whole time — everything from the big-picture stuff to the details. If I'm explaining a machine, it might be the relationship between gears; if I'm doing a city scene, it might be the scale of the buildings. I don't necessarily have that complete image in my head when I start, but I have to get it right.

I end up making more drawings than an organized person would. You should keep drawing until you're right. I keep drawing until I understand the subject matter. In the studio I have piles of sketches on tracing paper that are evidence of this ridiculous process. I've always learned best by drawing things.

SD: What is the role of frustration in your process?

DM: It's frustrating in that there are no shortcuts, at least I've never found them. I never feel like I've made the best drawing I can make, but I'm confident in the content of it. I know the information is solid, but I wish it were more accomplished in a draftsmanly way. And I never get there.

It is a tedious process. If you're setting out to make a picture of something, it's good to have a sense of what you're after when you start. I'm rarely that person. I have a vague sense of where we're going, but until I've really researched it and tried, and tried again, I'm not even completely sure what the problem is I'm trying to solve — let alone what the solution is. You might sketch something 10 times and realize that it's from the wrong point of view. So the frustration is part of the art, but dealing with it is part of the problem solving, which I really enjoy.

- Courtesy Of The Vermont Arts Council Spotlight Gallery

- "The Screw"

SD: In The New Way Things Work, you worked with Neil Ardley to add a chapter called "The Digital Domain." What was your experience of learning about and drawing more recent technologies?

DM: That brings up the word frustrating again. In a way, the new technology is much less interesting to illustrate. It's black boxes and wires and tiny little chips. When I can, I blow things up so the chip is huge [and] you can walk through. That's when I become most dependent on the experts to tell me what's happening, so I can begin to get a visual handle on the material and invent some way to make it accessible. And you really have to use your imagination at that point, because it's not inherently visually interesting. I see myself as a translator.

I much prefer to draw things you can actually see at work.

SD: Your work is very much about demystification. Do you have any strong opinions on mysticism/magic?

DM: No, not really. I enjoy magic like anybody. It's amazing to be amazed, and so refreshing these days to confront something you can't explain, but you just saw it — or so you think. Who doesn't just like to be amazed? Sign me up. It's so different from the work I do.

SD: Do you ever feel burdened by knowing so much about how things work?

DM: No, not at all, because I forget it all as soon as the book is finished. I was hoping you weren't going to ask me technical questions — but I know where the book is. With every one of these books, I become immersed in the subject matter. I think that every little space in my head is full. I start to forget people's names because my head is so full of information about new technology or old technology or whatever I happen to be working on. I know that stuff as long as I need to make the interpretation, the translation. But after a while, it's gone.

SD: What are you working on now?

DM: I just finished a book that comes out next May [Crossing on Time] about a steamship, an ocean liner called the United States, in Philadelphia. [It is] the fastest ocean liner ever built, comparable in almost every way, except for luxury, to the Queen Mary. It's 990 feet long. It's a wonderful piece of sculpture.

More importantly than anything, it's the ship my family came to this country on. I couldn't have cared less that I was on this ocean liner, the fastest ship — all I wanted to see was the Empire State Building. I didn't even realize that I was on this ship that was so significant. I just wanted to get to America, get to New York, see that building.

SD: So what's on the horizon, in terms of projects?

DM: I don't use the word "horizon" anymore after spending four years [working] on the ship. I would like to do something more playful, more fun, because I really like to have fun, to do some smaller books. I'd say children's books, but I never make books just for children. I'd like to do some more of those, and I'd like to do some more information books, but not big ones, not long ones — and I'd only want to do them in collaboration with an expert. Let me just be the interpreter.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.