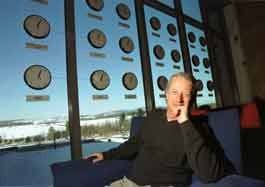

- Photo: Calen Kenna

Parker Croft considers Vermont, where his family goes back seven generations, to be “the most wonderful place on Earth.”

Accordingly, when the Middlebury architect and assistant professor visited a country on the opposite side of the planet five years ago, the maple sugar candy he brought along gave him an unanticipated entree to an ancient culture. Although he was in India to help establish a health-care facility, Croft found himself on a magical mystery tour that redefined his aesthetic sensibility as well as his notion of certainty.

“I began to comprehend how narrow our view of reality is in the United States,” he says, gazing at the snowy landscape outside his off-campus studio. “The public nature of my work became more pronounced after that.”

Croft, 51, says he agrees with the old saying, “Art is not an end in itself but a means of addressing humanity.”

In “Time For One World,” his installation on exhibit at Middlebury College’s Bicentennial Hall, the high-speed reality of Western life has slowed to the pace of 24 clocks and a steady beat intended to represent the human heart. Each clock is accompanied by a small plaque indicating a place with historical significance in the language or dialect actually spoken there: Wounded Knee is written in Lakota, Chernobyl in Russian, Hiroshima in Japanese, Bangladesh in Bengali.

The clocks, synchronized as “less a comment on time than on human events,” are affixed to floor-to-ceiling windows in a student lounge. They are intended to represent locations from each of 24 equal segments of the Earth’s surface, or 15 degrees each of the total 360-degree circumference. “The locations illustrate the world’s suffering from divisiveness, war, pollution and prejudice,” reads a statement Croft wrote to describe his purpose. “They are also examples of the triumph of a cooperative spirit over dissension and narrow self-interest.”

He has linked the clocks to the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, which occur at the same moment everywhere around the globe. So they each tell the same exact story in hours, minutes and seconds. The “heartbeat” comes thumping over a single loudspeaker, sounding somewhat subliminal.

But for a conceptual piece that doesn’t take up a whole lot of space, “Time” has gotten quite a bit of attention — and not all of it positive. One of Croft’s faculty colleagues dismissed it as “‘not legitimate art.’ Other people have complained that it blocks the view through the windows. There was even a petition to have the work removed before the exhibit’s close late Monday. Croft counters, “I don’t know any serious art that doesn’t promote controversy.”

Croft suspects that his critics might have reacted negatively to the piece because “it is not decorative. There is a strong architectural basis to the way it occupies the space. Or maybe they’re alienated by its scientific, intellectual nature.”

It’s the sort of art you might find at an airport, and Croft, appropriately, has offered to show it at Burlington International before it heads for an airport in the Hawaiian Islands this fall. Ideally, he also would like to see “Time” travel to many of the world’s trouble spots delineated on those multilingual plaques.

But, to understand his larger mission, it is necessary to first trek backwards with Croft to India — his second trip to the subcontinent. As a student at Williams College, he had participated in a 1970 exchange program that was fun but hardly exceptional.

“This time, I was going back to visit an elderly couple that had ‘adopted’ me and to look into setting up a clinic in the Punjab,” Croft explains the motivation for his 1996 trip, adding that a cardiologist friend who was supposed to accompany him had to cancel at the last minute.

Fate intervened again when Croft reached New Delhi: Due to concerns about terrorism, the government had canceled train service to the volatile Punjab. “People kept telling me about Pushkar, which has 550 temples in a desert surrounded by mountains,” he says. “I took a bus.”

Unable to fall asleep one night, Croft returned to a palace on a lake he had visited earlier that day in Pushkar. “There was nobody around, just pigs and cows. The stars were out. I heard fish catching bugs on the lake, peacocks waking up, bells and people chanting in the distance. Then I saw an old guy with a white beard open up the temples, light a lamp and incense and start to play a flute. He was playing for God, and I was eavesdropping. The sky began turning purple as the sun rose. The white buildings picked up the color. I kept looking back and forth from the sky to the buildings,” he recalls, then suddenly slaps both hands on a wooden table in his studio. “I thought, ‘That’s it!’”

Croft’s eureka moment gave him “an intriguing artistic idea, to work with multiple facets that catch light at different angles. For the next two weeks, I would draw for three hours every morning on ‘folded light’ designs that capture both the source and the result simultaneously. In my view, it was the first idea I’d ever had that was absolutely original.”

On that initial dawn of discovery, Croft took a walk once the sun had come up and stopped to watch a funeral in progress. “A boy with wild hair wearing a loincloth asked me to follow him to a cave in the nearby ruins. I went inside this dark cave, filled with smoke from a cooking fire, and found a holy man. I gave him maple sugar candy, which he offered to the goddess Kali before eating.”

When Croft left the cave, someone warned him that the holy man was an “agori baba, a voodo person, a bad thing.” Nonetheless, the American went back to bring some fruit to the baba, who then adorned Croft’s long, salt-and-pepper pony tail with a string of natural pearls.

Another man, a yoshi baba who spoke English, had joined the cave dwellers by then. Through him, the agori baba asked Croft if he knew anything about construction. The Harvard-trained architect said yes, and the entire entourage emerged from the cave. That’s when Croft noticed that the agori baba was a dwarf and the yoshi baba was a leper.

They took him along to inspect a parcel of land where the holy man’s followers planned to build a complex. “I drew a design in the sand that they seemed to like,” Croft says.

This experience kicked off a series of encounters with gurus and saints. At one point, Croft climbed a steep cliff to the top of a ridge. There, he came upon a little valley with mangoes, banana trees, frolicking monkeys and a man sitting on the porch of a tiny hut. Another baba. This one was rumored to be 120, though he did not look a day over 70, with a gift for predicting the future. Villagers were gathered, pleading for a winning lottery number. He refused.

Yet when Croft was encouraged to approach with a question, he simply asked if the well-preserved baba would like to see a picture of his 9-year-old son, who had recently started home-schooling back in Vermont. “The baba started crying. He told me to teach the boy to read and write but not to send him to a school.”

Already armed with enough mystical memories to fill the Bhagavad Gita, Croft returned to New Delhi so he could go to the proposed site for the health clinic with his surrogate father, who had been having some problems with the local “saint.” Again the maple candy came in handy. Croft sweetened the deal, and everything went smoothly.

Before leaving India, Croft decided to see Dharmsala, home of the Tibetan government-in-exile. He took a late-night walk in the Himalayan foothills, but the moon, which had been bright when he started out, disappeared. In the darkness, he suddenly observed a mesmerizing glow above a peak in the distance and wondered if it could be an angel. “I thought, ‘Omigod, this is extreme,’” says Croft, unaware at the time that he was witnessing the Hale-Bopp Comet.

“I went to India for the most pragmatic reason, so I never expected these amazing spiritual things would happen to me,” he surmises.

A changed man, Croft landed back in the Green Mountain State and began to concentrate on his “folded light” ideas. “I was completely on fire,” Croft recalls.

His first piece won an award at Burlington’s annual South End Art Hop, followed by a grant to show similar work at Middle-bury. A newer creation, called “Big Night,” sits in his studio capturing the diffused sunlight that floods the room. The angular 9-foot, 4-inch aluminum sculpture is painted in swirls of purple and, working somewhat like a trompe l’oeil, appears translucent despite being crafted with solid material.

Croft’s “Time For One World” offers less visual intrigue than the sculpture; in this case the puzzle, sufficiently complex to confuse a mathematician, is more cerebral. “The first time zones were adopted in 1883,” he says. “Daylight savings was not signed into law until Gerald Ford was president. Given the 24-hour nature of the Internet, existing time zones become ridiculous.”

His goal is to foster reflection. “In our normal day, society makes so many demands on us with all those truisms: ‘Time is money.’ ‘I don’t have time for that.’ We tend to see time as the enemy of relationships. I was hoping to provide a way for time to promote those connections.”

On a brisk April afternoon, several students camped out in Bicentennial Hall easy chairs are schmoozing, snoozing or studying — for the most part oblivious to Croft’s thought-provoking message about the human condition ticking away nearby. After all, these global clocks on a simultaneous, 24-hour can’t really tell them if they are late for class.

Perhaps a little maple candy would get their attention.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.