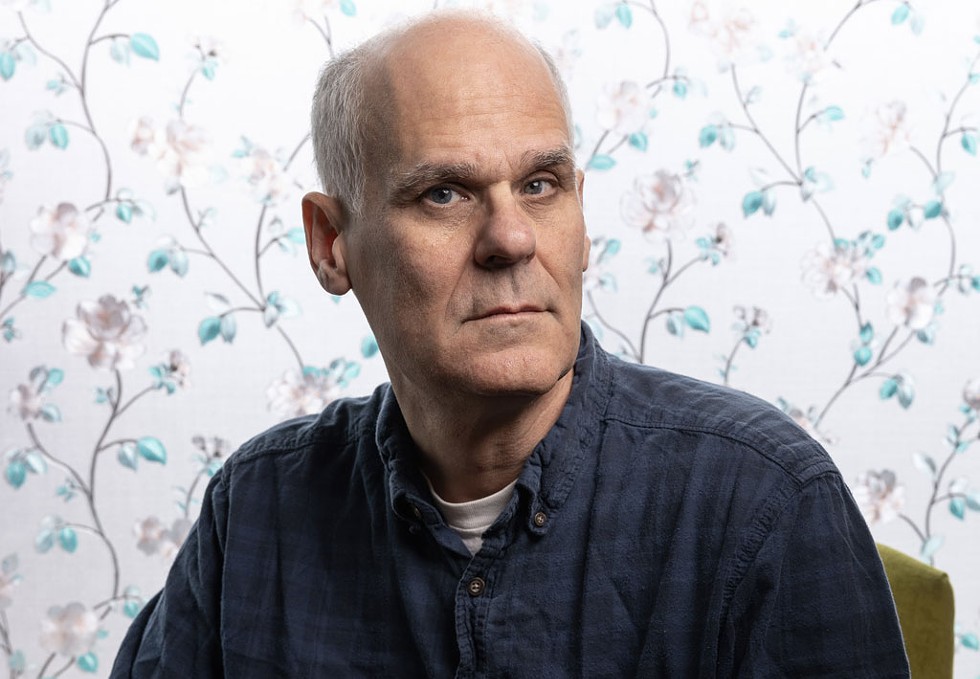

- Rob Strong

As he is wont to do, Bliss was joking. But also kind of not.

"I have nothing but praise for James and nothing but good things to say about him," Bliss went on. "I just wish that he would stop working so much."

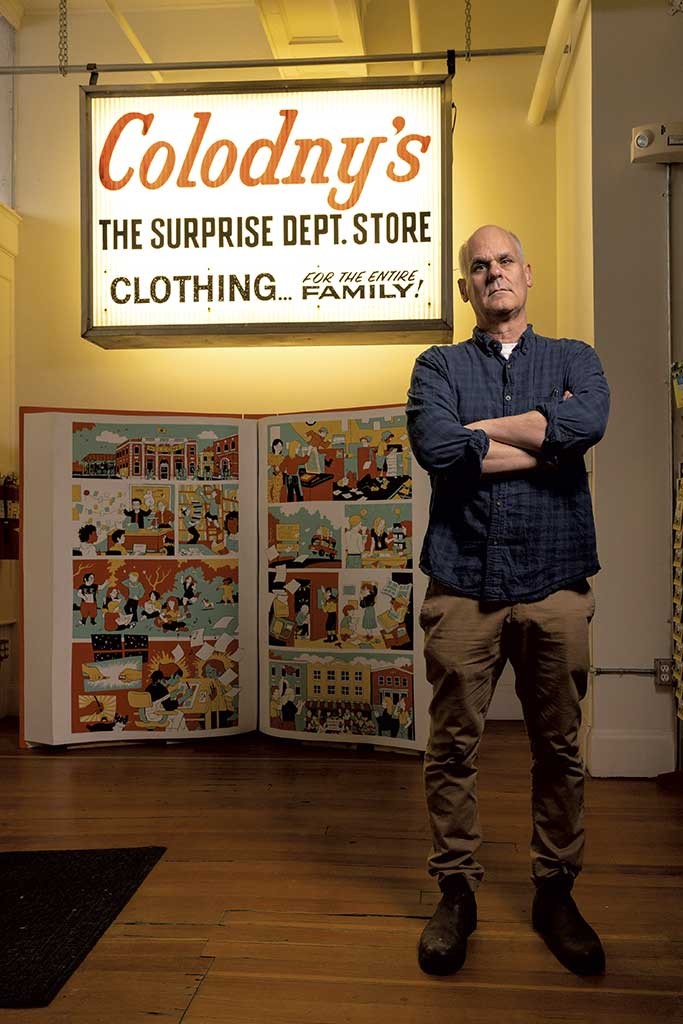

He has a point: By any measure, Sturm's 40-year career has been a breakneck series of successful creative endeavors.

In Vermont, the 58-year-old cartoonist is best known as the cofounder of the Center for Cartoon Studies, a one-of-a-kind college for cartoonists that he dreamed up and brought to life almost 20 years ago in what was then the dilapidated railroad town of White River Junction. In the years since, the school has produced a stream of artists who have gone on to stellar careers making and teaching comics.

All the while, Sturm has forged a glittering comics career of his own. He has written and drawn cartoons for Slate, the New Yorker and the New York Times. He was in at the ground level of two profoundly influential publications: innovative satire outfit the Onion and Seattle alt-weekly the Stranger.

- Courtesy

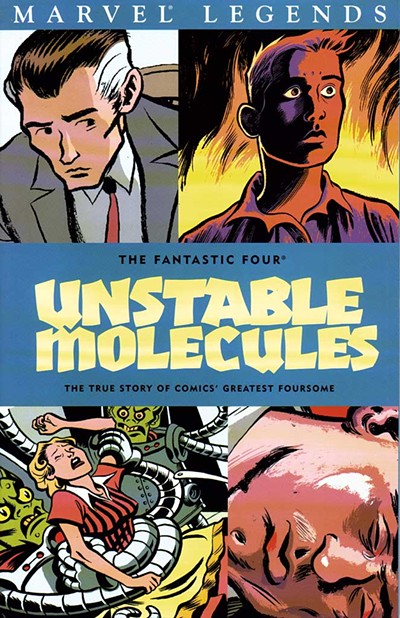

- Unstable Molecules

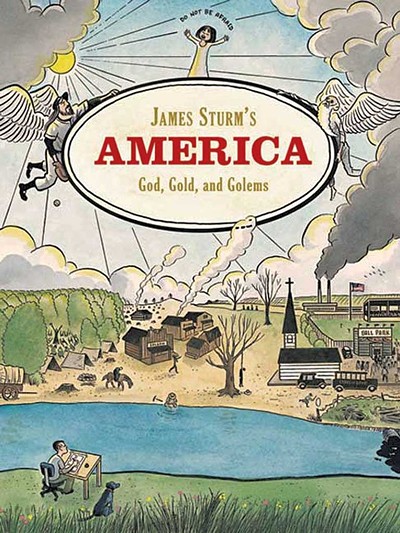

He has won an Eisner Award, aka "cartooning's Oscar," for writing a Marvel Comics miniseries called The Fantastic Four: Unstable Molecules. His epic, three-volume historical fiction book James Sturm's America: God, Gold and Golems drew widespread praise for its Howard Zinn-like excavation of the sort of U.S. history that's rarely taught in schools. His collaboration on the seven-volume-and-counting Adventures in Cartooning series has helped guide a new generation to the craft.

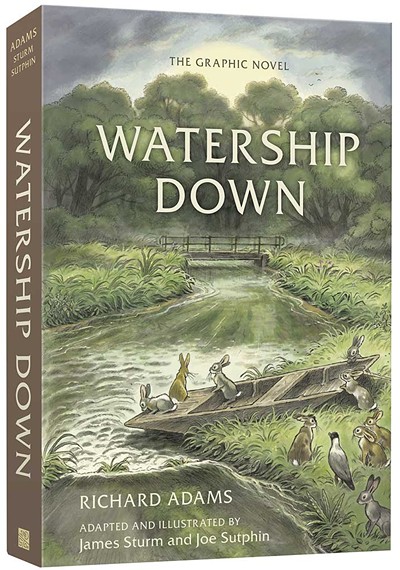

Yet it's his latest work that may stand as his crowning artistic achievement: a graphic novel adaptation of English author Richard Adams' 1972 fantasy classic Watership Down.

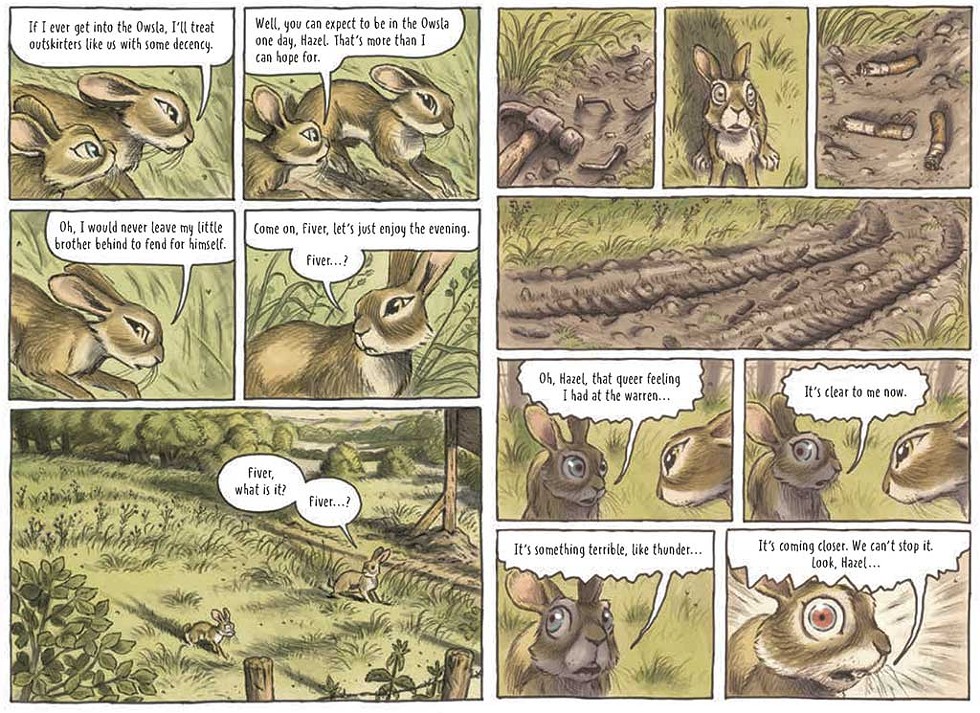

Released last month, the adaptation, conceived and written by Sturm with illustrations by artist Joe Sutphin, has been hailed as a brilliant interpretation that hews to the tone and scope of the original more faithfully than any previous adaptation.

Sturm and Sutphin's version is immersive from the opening page. The hefty 384-page hardcover book unfolds with minimal narration, relying instead on art and dialogue to unspool the epic journey of a ragtag colony of freedom-seeking rabbits led by Hazel and Fiver, a rabbit with a precognitive sixth sense. To slip into the pages of Watership Down as envisioned by the American artists is to be transported to a world of dark and mysterious mythology, adventure, and, of course, talking rabbits.

"It's a lot of rabbits," Sturm said wryly.

For Sturm, the book marks a creative milestone and yet another example of his uncanny ability to bring unwieldy and perhaps unlikely concepts to life. Whether crafting a rich adaptation of a beloved work of fiction, explaining complex and fraught topics through comics, or fostering a vibrant community of artists at his school, Sturm builds worlds through the sheer force of his creativity and ambition.

"He's really good at coming up with the big idea and then finding ways to execute it," said Jarad Greene, a cartoonist and Center for Cartoon Studies alum who now works at the school. "Not many people have both of those skills."

Origin Story

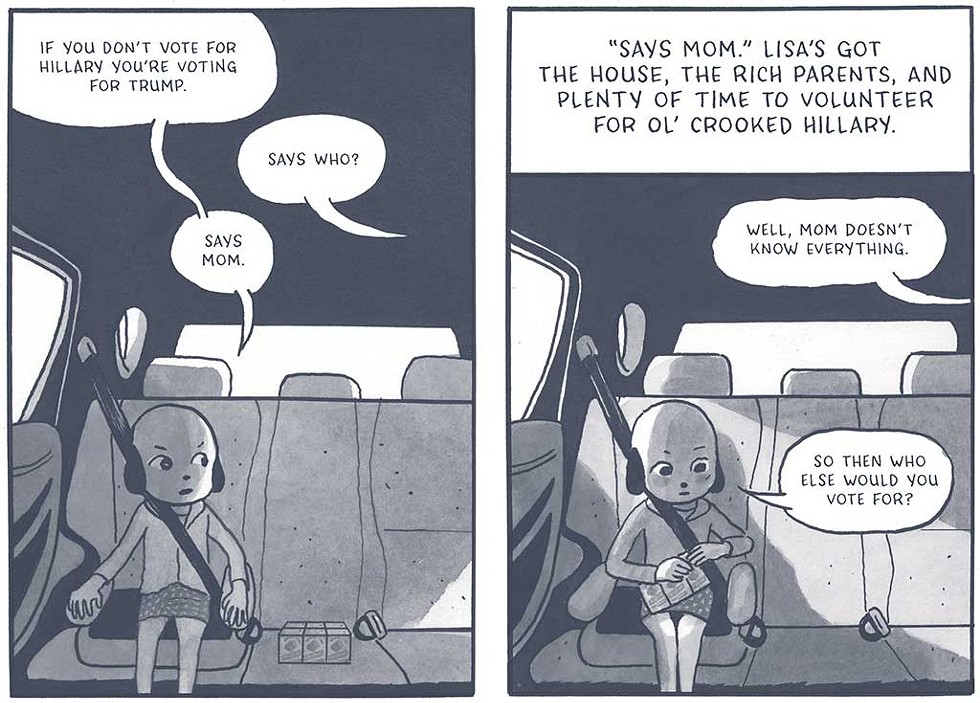

- Courtesy

- From Off Season

Sturm is tall and slim, with close-cropped salt-and-pepper hair that rings an otherwise bald scalp. He dresses casually, speaks thoughtfully and carries himself with an unpretentious, intellectual air that coexists with — and is perhaps softened by — a cartoonist's witty subversive streak. (When asked what he thought he could bring to a graphic adaptation of Watership Down, he responded, dryly, "Pictures.")

Even after more than 20 years of living and working in rural Vermont, he wouldn't be mistaken for a homesteader. But he does seem at ease in his surroundings. He shares a cozy house in Hartland with his wife, artist and printmaker Rachel Gross, and two dogs; it has the lived-in feel of a cabin in the woods and is where they raised their two daughters. Sturm credits Watership Down, one of the first books he borrowed from the Hartland library, with helping him embrace living in the middle of nowhere after spending his life until then entirely in cities.

"I had heard about it and thought, Maybe this will help me adjust to my rural lifestyle," Sturm said of the novel. "It inspired me to be more focused in the place that I was and [taught me] that amazing narratives can be found everywhere, even rural Vermont or, in that case, the English countryside."

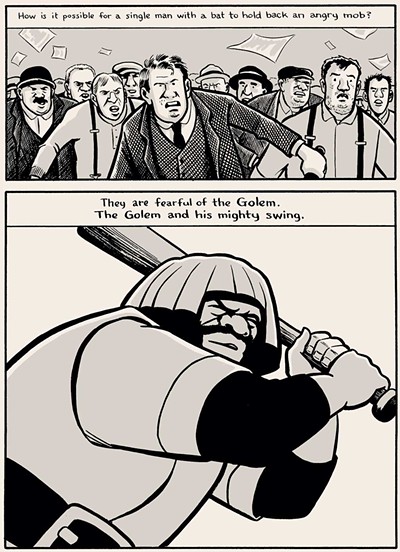

- Courtesy Of Drawn & Quarterly

- From The Golem's Mighty Swing

Sturm grew up 30 minutes north of New York City before attending the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he befriended the Onion cofounder Tim Keck and drew comics for the satirical newspaper.

Next came an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, earned while he worked as a production assistant at Raw, the alternative comics anthology coedited by Maus cartoonist Art Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, who is now art editor of the New Yorker. After graduation, Sturm followed Keck to Seattle, and in 1991 they cofounded the Stranger, a publication that helped set the standard for alt-weekly newspapers — including this one. While he was there, he met Gross.

All the while, Sturm was producing comics and making a name for himself, especially in underground circles. In 1991, Seattle's Fantagraphics published the first book in his Eisner-nominated Cereal Killings series. On its face, the offbeat murder mystery concerned out-of-work cereal box mascots who were targeted by a serial killer. But like a lot of Sturm's work — and the alt-comics of the era — that goofy premise concealed a deeper commentary. The series was inspired by Wendell Berry's 1977 book The Unsettling of America, which probes how diet shapes American society.

By 2000, Sturm and Gross were living in Georgia, where Sturm taught in the sequential art department at Savannah College of Art and Design. He was still working on comics, including what would be his breakthrough 2001 graphic novel, The Golem's Mighty Swing, the final installment of the trilogy that became James Sturm's America.

- Courtesy

- James Sturm's America

"That book put me on the map," Sturm said. Time magazine's Best Comic of 2001 also led to bigger opportunities, including drawing a New Yorker cover and realizing a boyhood dream of writing for Marvel.

Although his career was flourishing, he and Gross had soured on life in Savannah and wanted a change. Meanwhile, Gross' parents' small summer house in Hartland, Vt., stood empty. So the couple and their 1-year-old daughter moved north.

Within a year, Sturm and Gross welcomed a second daughter, and while Sturm was still drawing comics, and accolades, he needed a steadier income. Leaning on the experience he gained in Savannah, he decided to try teaching comics. On a map, he drew a circle with a 100-mile radius around Hartland and pitched every college in the area.

"When I say there was no interest, I mean there was no interest," Sturm said. A few schools in Vermont and elsewhere offered to let him teach a drawing course, but none seemed keen to take cartooning seriously.

"I didn't want to go to a place where I had to convince people that comics were important," Sturm said.

So he started talking with friends about the idea of an independent cartoon school. Soon his thoughts turned to the DIY ethos of the underground comics he fell in love with as an undergrad in Wisconsin while he was penning his first regular strip for the student-run Daily Cardinal, "The Adventures of Down and Out Dawg."

"The credo of underground comics was about self-publishing and doing it yourself," Sturm said. "That was the mindset of the group of auteur cartoonists I was in in the 1990s. So the thought was: Can we take that mindset and apply it to higher education for comics?"

Applying Himself

- Courtesy Of Macmillan Children's Publishing Group

- From Adventures in Cartooning: Characters in Action

In the early 2000s, White River Junction was notable mostly for its bus station and as the place where northern New Englanders returned their Netflix DVDs. Its once-thriving downtown was largely deserted, its Main Street haunted by the ghosts of shuttered mom-and-pop businesses.

With its seedy reputation, the River City was not the kind of place most sensible folks would stop for lunch, let alone a master's degree in fine arts. But as he's made a career of doing, Sturm saw things differently.

"You had all this underutilized infrastructure, boarded-up buildings that were empty or needed work," Sturm said. "So we were able to find cheap places to move in."

Sturm found a partner in his friend Michelle Ollie, a graphic designer with an MBA and experience as an academic administrator. They cobbled together a hodgepodge of funding, including donations from "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" cocreator Peter Laird and Jean Schulz, widow of "Peanuts" creator Charles M. Schulz, for whom the Center for Cartoon Studies' massive Schulz Library is named. Two of Sturm's friends and mentors also raised money for the school: Spiegelman and the late Vermont-based New Yorker cartoonist Ed Koren.

Sturm and Ollie welcomed their first students in fall 2005. They've never looked back.

"I think timing had a lot to do with the success of the school," said Bliss, who lives in nearby Cornish, N.H., and, through the school, hosts an annual monthlong residency for visiting cartoonists at his home. "White River needed the school. And comics were kind of breaking out."

According to Greene, the school's administrative and development coordinator who earned his MFA there in 2016, "A common trait of cartoonists is having a bit of a rebel spirit." Sturm, he opined, "really embodies that."

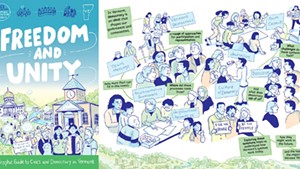

- Courtesy

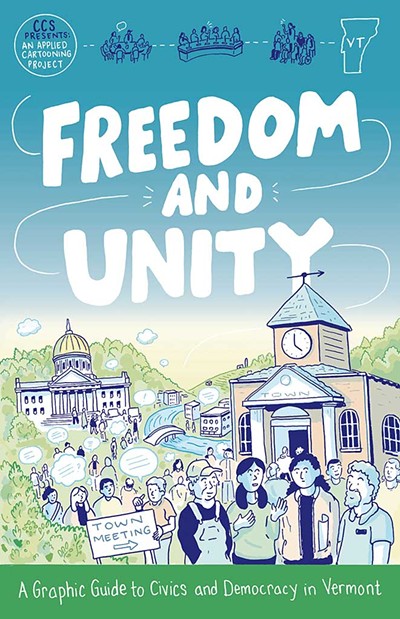

- Freedom and Unity

Sturm is quick to share credit for the center's success with Ollie and allies in state and local government. He wondered aloud how many other states would agree to designate a cartoonist laureate every three years, as Vermont has done in conjunction with the school. (The answer, in fact, is none.)

"Not to undersell my own contributions," Sturm said, "but all of these conditions had to align for this to work."

And it has worked. The school offers a two-year master of fine arts degree program, one- and two-year certificates, and summer workshops. It routinely meets its enrollment numbers — between 14 and 20 students each semester — and has produced a parade of successful cartoonists, including AP Sports "Daily Draw" creator Dan Archer, New York Times best-selling author Andy Warner, DC Comics illustrator Robyn Smith and current Vermont cartoonist laureate Tillie Walden.

Dan Nott graduated from the school in 2018 and now teaches a history of comics course there. His debut nonfiction graphic novel, Hidden Systems: Water, Electricity, the Internet, and the Secrets Behind the Systems We Use Every Day, was long-listed this year for a National Book Award in Young People's Literature. He said the school offers more than just an education in cartooning.

"Some people come here and maybe have never even met another cartoonist," Nott said. "Comics is often a pretty solitary endeavor, and I think a lot of the reason people come to the school is to find that community."

And it's a diverse community. Students come from as far away as Australia and from a variety of backgrounds.

"We definitely have an eclectic mix of students who come to CCS, and that interesting mix of people is making White River more interesting," Greene said.

It's also making White River more money. Students who come to the school rent apartments, shop at the Upper Valley Food Co-op, and work (and eat and drink) at spots such as the Tuckerbox Turkish café and the Wolf Tree cocktail bar. Ollie estimates that in its first years, the school injected $800,000 annually into the local economy. That figure is up to around $2.5 million now, she said, and may even be higher.

For all the good the school has done in White River, its latest endeavor, conceived by Sturm, is an attempt to make the rest of the world a better place, one comic book at a time.

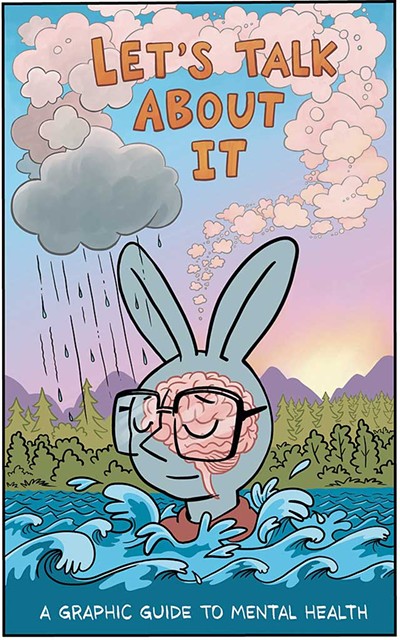

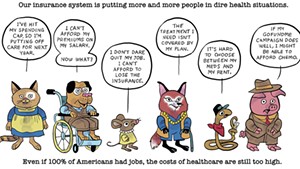

- Courtesy

- Let's Talk About It

In October, the center christened its Applied Cartooning Lab, where students and faculty work with outside organizations on mission-driven, community-based nonfiction comics, such as its collaboration with the Vermont Secretary of State's Office last year on Freedom and Unity: A Graphic Guide to Civics and Democracy in Vermont and Let's Talk About It: A Graphic Guide to Mental Health.

Applied cartooning has always been part of the school's curriculum and mission in one form or another, Sturm said, but the new lab formalizes the program and its myriad projects.

"It's a place for us to put it all under one banner," he said.

The lab has tackled some weighty subject matter, from mental health to climate change. Its next book, a collaboration with Harvard University's Prison Studies Project, is on mass incarceration. If that doesn't quite sound like a lighthearted jaunt through the Sunday funnies, it's not. But to Sturm, that's precisely why nonfiction comics are effective vehicles for breaking down fraught topics.

"That's just comic book stuff, right? Something you laugh at," he said, summing up a would-be reader's mindset. "I think that's the strength of it — that people don't take it seriously. You might pick it up, get inside it, and the next thing you know, you're absorbing information, learning stuff."

Avengers Assemble

- Courtesy

- From Watership Down

Sturm first read Watership Down when he was trying to understand what it meant to live in the woods. He read it again for each of his daughters when they were children, sharing with them the tale of a small band of rabbits who face a series of dangers as they seek a new home after destruction of their warren. Later, he read the novel with a class of Cartoon Studies grad students as a sort of impromptu book club.

His torn and tattered copy of Watership Down was still on his bookshelf when his agent called in 2018: The estate of Richard Adams was looking for a cartoonist to adapt the book as a graphic novel.

First published in 1972, Watership Down follows the adventures of Hazel, Fiver and their friends as they evade death at the hands of humans and predators, rescue themselves from captivity by an authoritarian band of enemy rabbits, and triumph in a final, epic battle. The story has been adapted many times — most notably in a 1978 animated film and a 2018 animated Netflix series. But due to a controversy over who owned the rights to the novel, Adams had little input on those projects. The graphic novel is the first adaptation since the book's rights were restored to the Adams estate in 2020.

Sturm had tried reading Watership Down as a kid but only made it as far as Adams' page-and-a-half-long opening description of a meadow before putting it aside. When he returned to the novel 30 years later, though, he wished he'd stuck with it because the book brought him back to the comics he loved in his youth.

"It's this kind of motley crew of outsiders. They have to flee their home. They have to learn to work as a team to overcome, like, all manner of dangers and supervillains," he said. "One's super fast, one's super smart, one's super strong, one has psychic abilities — it's like describing, like, the X-Men or the Avengers.

"There was that aspect of the book that felt like the comic books I loved as a kid," he continued. "So actually making Watership Down into a comic book was exciting."

Sturm wanted the job — but despite his decades of work at the drawing table, he never considered illustrating the book himself. For one, he said, he's too slow. For another, his simplistic style would have been an odd fit for the book.

Sturm was "mesmerized" by Marvel Comics in his youth but said he never developed the hyper-detailed style of illustration signature to superhero comics. Part of what drew him to underground comics in the 1990s was that they embodied the idea that cartoonists needn't be artistic savants. While he's no slouch with a pencil — Bliss calls him "one of my favorite living cartoonists" — Sturm's earnest, more alternative style "would not have made sense" for Watership Down, Sturm said.

So he recruited Sutphin, a children's book illustrator with whom he shared an admiration for the softly drawn pen-and-grease-pencil newspaper cartoons of Depression-era artist Denys Wortman. Sutphin's similar realistic style and love of drawing the natural world seemed perfect for the adaptation.

Sturm's proposal to the Adams estate and Adams' two daughters, Rosamond Mahony and Juliet Johnson, promised a graphic novel that would remain faithful to the story and spirit of Watership Down.

"Ros and I wanted to preserve the hope and the uplift of the story in the graphic novel," Johnson wrote in a recent email to Seven Days. "James and Joe absolutely got this."

Sturm and Sutphin also got the gig.

Strangers in the Field

- Courtesy

- Joe Sutphin

Johnson explained that while she and her sister understood that elements of the story would be lost in the translation to a graphic novel, they hoped Sturm and Sutphin would "convey the beauty and lyrical quality of the Hampshire countryside."

That was a potential problem.

While Sturm's home in the Upper Valley town of Hartland is a stone's throw from New Hampshire, it's roughly 3,000 miles from the rolling meadows of Hampshire, the English county where Adams wrote and set his novel. And Sutphin lives in Ohio.

How then, could Sturm and Sutphin sweep readers away to that landscape, as Adams had done in his lovingly rendered descriptions, without themselves being immersed in the English countryside?

"That was one of the big questions," Sturm recalled one October afternoon in the kitchen of his home as he prepared shepherd's pies for a dinner party he was hosting for Bliss and other cartoonist colleagues that evening. "One of the things I love about the book is the nature writing; Richard's descriptions are so beautiful. How could we do that justice?"

He gestured to a picture window above the sink. Beyond it lay a meadow of wildflowers and ferns that rolls to the edge of a forest. Particularly on this drizzly day, it wasn't hard to imagine the scene outside as a stand-in for Adams' English countryside. Sturm had often done just that while reading and rereading the book — which gave him an idea.

In an early meeting with their editors and Adams' daughters, Sturm suggested: "What if we set the story in Vermont instead of England?"

Adams could probably have described in rapturous prose the crickets that greeted Sturm's suggestion.

"I knew it was about the dumbest thing I could have said as soon as it left my mouth," Sturm recalled.

Suffice it to say, Adams' daughters were unimpressed. A few days later they invited Sturm and Sutphin to visit their Hampshire.

The sisters walked with the two men along the real-life Watership Down, a sloping hillside that is indeed home to a multitude of rabbits, and the locations that inspired their father. Sturm and Sutphin took hundreds of photos along the way, at times crawling on their bellies to get a "rabbit's-eye view" of the place.

In the book, Adams sometimes spends pages just describing the surroundings. In the graphic novel, Sturm and Sutphin could set scenes in just a few panels.

"This is a visual medium, so you can show those things," Sturm said. "And I think one of the brilliant aspects of the book is just how beautifully the English countryside is depicted. The forest, and how lush it is — it's really quite stunning to look at what Joe accomplished."

Back in the States, Sturm mapped out the story's flow, chose the dialogue and selected the scenes to be illustrated. He wrote a script and then drew thumbnail sketches for every panel — a few thousand in all — essentially creating a storyboard, on which Sutphin based his artwork.

One of the challenges was how to tell all the rabbits apart. Adams' daughters were adamant that the animals look like real rabbits and not be Disney-fied. Here, Sturm took a lesson from his old boss, Spiegelman, who encountered a similar challenge with the mice in Maus, a graphic novel about his father's Holocaust experiences. Spiegelman used staging and subtle visual cues to distinguish his mice. He also used his mice's names in dialogue as much as possible.

Sutphin explained that when rabbits in Watership Down are seen at a distance, they look like wild rabbits. But for close-ups, he gave them expressive, almost human eyes to convey emotion. The clairvoyant Fiver, for example, is often seen with wide, searching eyes. Bigwig, the soldier, sees the world through a narrower focus.

Those tricks were especially important for Sturm and Sutphin, as their version of Watership Down is largely free of narration. Images and dialogue, often taken directly from the novel, tell the story.

"It's an adventure story," Sturm said, adding that exposition would be jarring and pull the reader out of the tale. "I tried to keep the text pared down so that the pictures tell the story and you're moving right along with the rabbits."

Variations on a Theme

- Courtesy

- Watership Down: The Graphic Novel, By Richard Adams; Adapted By James Sturm And Illustrated By Joe Sutphin; Published By Ten Speed Graphic, 2023

As the legend goes, Adams began telling his young daughters the tale that would become Watership Down to keep them entertained on long car rides. It evolved over many years and countless retellings before he finally, at the urging of his daughters, wrote the version the rest of the world came to know and love.

While he invented the fable for his children, and its stars are talking animals, Watership Down isn't exactly for kids. It's long and at times dark and violent, with complex themes beyond the scope of most children's books — even if Adams never intended the story to convey them.

Over the years, the book has been interpreted as an allegory for the Holocaust, a Christian parable and a cautionary environmental tale. It's been championed as a rebuke of communism in some corners and as pro-Marxist in others.

To his dying day in 2016, at age 96, Adams maintained that Watership Down was not allegorical and contained no deeper meaning or social or political commentary.

While Sturm is suspicious of that position — "I don't buy it," he said — as he adapted the novel, he channeled Adams and focused solely on telling the story.

"I'm not putting my thumb on the scales with the parables or metaphors," Sturm said, "because there's a lot of stuff in there that can be read differently. And I don't feel like it's for me, in any sense, to weigh in on that. Just tell the story how he told it."

With apologies to Adams, it's hard not to ponder deeper meaning in the pages of Watership Down. Even if he didn't mean for any to be there, generations of fans have gone looking and found ... well, something. And with Sturm and Sutphin's help, new generations may, too.

Much as applied cartooning can introduce unsuspecting readers to new ideas and lower the barrier to entry for engaging with complex topics, Sturm thinks the graphic novel might similarly offer new readers a bridge to Adams' story.

"I think what this graphic novel adaptation can do is ... introduce this book to some young readers who might be intimidated by the book," he told Vermont Public's Jenn Jarecki during an October press junket. "My hope is that it kind of leads people back to the original text."

What readers will find in Sturm's Watership Down is anyone's guess. But if history is an indication, the story's themes will continue to resonate.

"It's a universal story, of course, seeking the promised land," Adams' daughter Johnson wrote of the book's lasting appeal. "And there are a lot of messages about hope in adversity, good and bad leadership, and comradeship. Dad wrote from the heart, having been marched off to war aged 20. So he was also saying something about being young, and being placed in an almost hopeless situation. I think a lot of people relate to that."

It's also possible — likely, even — that the meaning of the story will change for a reader over time.

As Sturm pored over his dog-eared, taped-together copy in 2020, the world was plunged into darkness. Adams would surely bristle at his book being made a pandemic parable, though at least one passage does a pretty good job of encapsulating the consuming fear — and hope — of that era:

"All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you, digger, listener, runner, prince with the swift warning. Be cunning and full of tricks and your people shall never be destroyed."

"Suddenly this book I'm living in, it was really quite a source of comfort," Sturm said. "And it felt like the things I needed to keep reminding myself of were the things I was reading and adapting."

The Work of Art

- Rob Strong

- James Sturm at the Center for Cartoon Studies

Sturm doesn't disagree with Bliss about his extreme work habits — at least not entirely. It's just that sometimes he can't help himself.

"I'm really curious about things," he said, "and my way of understanding the world is through comics."

Whether it's working on comics about strung-out cereal box mascots or mental health, or reimagining a literary classic, he loses himself in the process.

"It becomes an immersive experience where I engage with folks and I learn a lot," he said. "And oftentimes, even as an editor, I feel like I'm in the front row to something really cool."

But his compulsion to work is not solely about chasing a creative high. It's also born of necessity.

"I'm an educator and an artist," he noted. "And these are things that are not highly valued or well compensated in our society. So you have to have a lot of balls in the air to make it work."

Still, he does worry about spreading himself too thin.

"I can't help but think of that question as a criticism," he said. "And I think it's a fair one that I ask myself sometimes: Am I giving projects the attention and depth that they need?"

The continued success of his Cartoon Studies students and his adaptation of Watership Down — currently the top-selling graphic novel on Amazon — suggests that he is.

Of course, Sturm has more projects coming — he always does. The Applied Cartooning Lab's book on mass incarceration is nearing the finish line and should be published next year. He's collaborating on another nonfiction project, about plant-based diets. And he's working on a graphic version of Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking. The 1985 book by David Bayles and Ted Orland has achieved a sort of cult status among artists for demystifying and, more importantly, humanizing how and why we make art. It was hugely influential on Sturm.

As Bayles and Orland wrote, "Art is hard because you have to keep after it so consistently. On so many different fronts. For so little external reward ... You have to find your work."

Sturm seems determined to do exactly that.

"If I won the lottery or something and I got $10 million tomorrow, I think 90 percent of what I'm doing is what I'd want to be doing," he said. "I don't know how much I would change."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.