- Courtesy

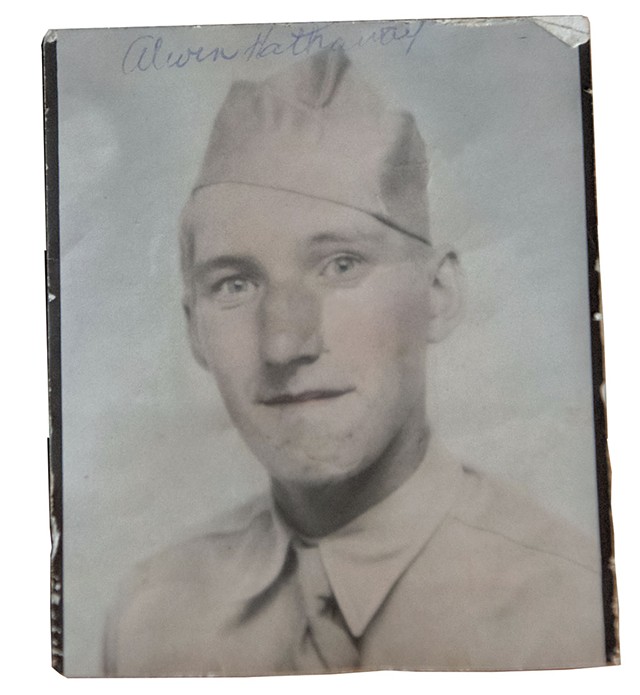

- Pvt. Alwin Hathaway

It was just another school day in November 1944 when 12-year-old Wilma Hathaway rode home on the bus with a dozen or so schoolmates along Route 116 in Hinesburg. Just another day, until the bus driver chose to announce to the children that Pvt. Alwin A. Hathaway — Wilma's older brother — was missing and presumed killed in action in Germany.

Every eye on the bus swept toward Wilma, whose face turned rigid with shock. When the driver reached her stop, Wilma leaped from the bus and ran to her house, where she saw the horror of affirmation in her mother's face — Lola Hathaway had received a telegram from the United States Army. Wilma dropped her books on a table and ran out the back door into the woods.

As she recounted this memory in her Williston living room, Wilma, now 90, did the same thing she had done 78 years ago: She shook with sobs.

The wages of war are paid in blood, tears and body bags. Loved ones in their prime, once bursting with bravado, are sent home in flag-draped coffins. But what happens when Johnny is not marching home because he's nowhere to be found? When, as in the case of Pvt. Hathaway, there is no body?

He was in a battle. We lost track of him. Not accounted for. We presume he died in battle. Sorry for your loss.

The family mourns — what else can they do? Absent tangible evidence, the family grieves and moves on.

The Army does not move on. In the 1970s and '80s, American homes sprouted thousands of black-and-white POW/MIA banners, bleak mementos of the Vietnam War memorializing captured or missing soldiers. And there was unfinished business from the Korean War, as well as World War II.

Reducing the number of those banners is the mission of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA — imagine the reality of a kind of "CSI: War." Forensic scientists sift though the remains recovered from battlefields to identify unknown soldiers — to give them back their names, restore their humanity and grant their loved ones the certainty, however bitter, that they crave.

For nearly 78 years, Pvt. Hathaway's family has been denied such closure. There was agreement about the battle that claimed him and little doubt about the location where he met his end. But without a body, the rest was conjecture.

In 2017, conjecture escalated to hope. A DPAA investigation of remains from where Pvt. Hathaway was believed to have died suggested 15 possible identities for the soldier designated as "X-2739." Then, thanks to some dogged historical research, cutting-edge science and, bizarrely, a mundane 80-year-old clerical error that revealed a critical clue, the DPAA made a near certain identification last year. A DNA match with a family member confirmed it.

And now, three-quarters of a century after he died on a German battlefield during World War II, soldier "X-2739" has a name. Pvt. Alwin Arthur Hathaway is coming home.

'He Was a Good Brother'

- Courtesy

- Wilma Hallock (now 90) as a young girl

Wilma Hallock, née Hathaway, lives with her daughter, Starlene Poulin, in the latter's home in Williston. "I always liked that name; it was different," Wilma said, as her daughter smiled, "and people have, naturally, called her Star."

Sitting on a couch, Wilma relaxed into her story of Alwin, occasionally needing a prompt or a reminder from Poulin. They referred often to a thick binder presented by the Army, a kind of war biography of her brother.

Alwin was eight years older than Wilma, but he treated her like a much closer sibling.

"He was a good brother," Wilma recalled. "He was so tall. He used to walk me to school sometimes. He taught me how to throw a fastball — which came in handy when I got mad."

Wilma called her brother "something of a daredevil."

"If he saw something going on, he'd jump right in," she said, noting that her parents "would get after him sometimes."

"Sometimes he'd get into mischief," she said.

Alwin was drafted in February 1942, "as soon as he turned 18," Wilma said. "My parents didn't want Hitler taking over — but they didn't want to give up their son, either."

Mother and daughter agreed that Pvt. Hathaway looked smart in his uniform, and Wilma said he had a serious girlfriend he met in Europe — an English girl — whom he intended to marry and bring home

"She wrote to my mother for years after, even after she got married," Wilma said of that girlfriend. "She had a couple of children. She had my brother's emblem and picture, and she exchanged pictures with my mom."

On November 6, 1944, Pvt. Hathaway was reported MIA: missing in action.

In a letter to Pvt. Hathaway's parents, Maj. Gen. Edward F. Witsell, the acting adjutant general of the Army, wrote: "The record concerning your son shows that he was a member of a reconnaissance patrol operating within the vicinity of Hürtgen, which is approximately twenty-five miles southeast of Aachen, Germany. The troops within this area were subjected to an intense enemy artillery barrage and I regret to state that your son has been neither seen nor heard from since that time."

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest was actually a series of battles that took place over three months beginning on September 19, 1944, just east of Germany's border with Belgium. Though it was the longest WWII battle fought on German soil and one of the costliest — estimated U.S. losses were as high as 56,000 killed and wounded — the conflict is often overshadowed by what immediately followed, the so-called Battle of the Bulge.

Hürtgen Forest is a 54-square-mile woodland — an ambusher's dream, heavily sown with thousands of German S-mine land mines, referred to in soldier's jargon as "Bouncing Bettys." The winter was unusually cold and wet; many combatants suffered frostbite. Company E of the Army's 109th Infantry Regiment was involved in the fighting, including 20-year-old Pvt. Hathaway.

Remains were recovered from Hürtgen Forest in May 1946, but no identification could be made and, in December 1950, Pvt. Hathaway's body was declared "non-recoverable." The remains were buried with other unknowns at the Ardennes American Cemetery in France.

In May 2017, "based on historical research and analysis," a DPAA historian detected a strong association between those remains and Pvt. Hathaway. On January 14, 2021, after the remains were exhumed and transferred, the DPAA identified those of Pvt. Hathaway at its laboratory at Offutt Air Force Base near Bellevue, Neb. Scientists typically analyze skeletal remains and dental conditions and collect mitochondrial DNA.

In Williston, Poulin said her mother had never completely given up on seeing her brother again.

"That's one of those things I think we all try to hold on to," Poulin said. "I mean, you're always pretty sure that they're gone. But you still leave an open heart for that place, just hoping that someday he'll show up. I know I did, and I never met him."

Many factors make the path to identification long, including clearing the minefield to retrieve the remains and delays in obtaining DNA samples from family members for comparison. Another common complication is false clues, such as the rain poncho found in Pvt. Hathaway's kit that belonged to a different soldier. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting staffing problems at the DPAA didn't help, as well as the hallmark of any large organization (and particularly government): bureaucracy, a factor cited by several military and civilian officials.

Ironically, it was an Army screwup that provided a crucial clue in Pvt. Hathaway's case. Because his first name had been misspelled when he was inducted — the Army wrote "Alevin," not the correct "Alwin" — Pvt. Hathaway carried his birth certificate with him until the day he died. It was badly decomposed, but a remnant was readable.

What's in a name? A hell of a lot.

Eventually, DNA samples from Poulin and her mother provided the conclusive evidence for identification. Poulin said she accepted the reasons for the long delay, particularly the need to sweep the minefield in Hürtgen Forest.

"They knew there were soldiers there, but they couldn't go and get them because of the mines," she explained. She added that the false lead of the poncho, of soldiers swapping items with their names on them, "is very common," hence the need for DNA from relatives.

Through the DPAA investigation, Wilma learned that her brother had been in a foxhole when shrapnel from a mortar round or a mine pierced his skull. Likely, the pain was as brief as the flash.

When Wilma finally heard how her brother had died, "She cried," Poulin said. "She was very emotional, and I think she was almost at a loss for words. She just had tears. But there were good tears, in a way, to know that."

'Time Has a Way of Healing'

- Sasha Goldstein

- Pvt. Alwin Hathaway's grave site in Hinesburg

On the afternoon of July 7, Michael Mee, chief of identifications of the Army's Past Conflict Repatriations Branch, drove onto the gravel driveway of Poulin's home in Williston to meet with her and Wilma about Pvt. Hathaway. With him was St. Albans' Sgt. Jamie Thompson, a human resources specialist of the Vermont Army National Guard.

By his own estimate, Mee has averaged 30 of these visits each year for 12 years. It was Sgt. Thompson's first. Understandably, she was nervous — even, as she would say later, a little frightened.

Mee spent 20 years in the U.S. Air Force, including some time in mortuary affairs; he often initiated the dreaded doorbell ring signaling a service member's death. In his current job in the Army repatriations unit, based in Fort Knox, Ky., he theoretically is delivering welcome if not good news: a missing loved one found. The end of uncertainty. Closure.

These repatriation cases are different from having to announce a sudden, unexpected death, Mee explained in an interview.

"Time has a way of healing," he said. "So it's nice to be able to sit down with [families] face-to-face, fill in the blanks, explain exactly what happened to their loved one and how exactly he was identified."

With each family, Mee reviews mortuary benefits explaining how the military will return soldiers' remains home for burial with full military honors. He also brings a thick binder, such as the one Wilma and her daughter received, a dossier of the deceased's service record and whatever documentation has accumulated during the process of identification and repatriation. He begins visits by asking family members to tell him something about the deceased.

"We like to hear stories about the service member ... because we try and make it into a positive," Mee said. "After all the years they have been missing, these tend to be good-news cases. Their loved one is finally going to be coming home for burial."

Sgt. Thompson did not know what to expect when visiting Wilma and her daughter. "This was my first time, so it was ... a little bit scary," she admitted. But, she went on, "it actually turned out to be, like, a really good thing."

Sgt. Thompson said she anticipated that a visit announcing a soldier's more recent death would be "a lot harder on the family." The experience with Wilma and Poulin was a positive one because "they didn't know exactly what had happened or where his body was." Now, she continued, "he's coming back home."

- Daria Bishop

- A photo of Pvt. Alwin Hathaway along with his medals and the letter, sent in 1945, informing his parents of his MIA status

During the nearly four-hour visit with Wilma and Poulin, Mee asked Sgt. Thompson to present Pvt. Hathaway's combat decorations — the Bronze Star Medal and the Purple Heart — to the family, who received them tearfully. "I felt so grateful to be able to do that," Sgt. Thompson said. "To be a part of that was really awesome ... and Wilma, his sister, she's just really sweet."

Making up for lost time may seem poor recompense, but Pvt. Hathaway's homecoming is being handled with reverence.

Sgt. Thompson said she is coordinating with officers from the Fort Drum, N.Y., Army base to prepare for Pvt. Hathaway's graveside service. Associate Rich O'Donnell of Ready Funeral Home in Burlington said he was preparing to cremate the remains whenever they arrive, per the family's wishes. Because some airlines do not transport human remains, it is unclear whether they will arrive at Burlington International Airport, Boston's Logan Airport or Albany International Airport in New York.

Pvt. Hathaway is also memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the Netherlands American Cemetery in Margraten.

On Saturday, September 3, at 1 p.m., with full military honors, Pvt. Hathaway will be laid to rest with his parents, William S. "Nick" Hathaway, who died in 1955, and Lola May Burritt Hathaway, who died in 1977, in the Hinesburg Village Cemetery. A gravestone dedicated to Pvt. Hathaway has waited for decades, a sad placeholder.

"My only wish," Wilma said, her voice breaking and tears flooding her cheeks, "is that my parents had lived to see this."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.